Gauri Gill's search for the desert rose

By abandoning a preset narrative, photographer Gauri Gill found inspiration and passion in rural Rajasthan

When ForbesLife India met photographer Gauri Gill in June at a cafe in Nizamuddin East, Delhi, her works were on show at Galerie Mirchandani + Steinruecke in Mumbai (till July 31). For Gill, 46, these photos are part of her ongoing engagement with desert communities from rural Rajasthan. Composed of three individual series, the first two —‘The Mark on the Wall’ and ‘Places, Traces’—comprise pure pictures and the last —‘Fields of Sight’—surprises us with a collaborative set of photo-paintings with celebrated folk artist Rajesh Vangad.

Gill is a longtime exponent of the craft, having exhibited at several leading institutions including London’s Whitechapel Gallery, Philadelphia Museum of Art and National Gallery of Art, Warsaw. Her work is displayed in prominent North American and Indian collections, including the Freer and Sackler Galleries of Art at the Smithsonian Museum in Washington DC, Devi Art Foundation, New Delhi, and the Fotomuseum in Winterthur, Switzerland. In 2011, she was awarded the Grange Prize, Canada’s foremost award for photography. Here are edited excerpts from a conversation:

Q. Since 1999, your photographic practice has drawn you to communities living in the desert. How have things changed over time?

It’s astonishing that things have changed so little in these years: The road that ended at the school now goes up to the dhani (hamlet); electricity is available for more hours in the day but is still irregular; the school has moved from class 5 to class 8. In Delhi, meanwhile, the ground beneath our feet has literally moved in these post-liberalisation years, in ways both good and bad, but where’s the corollary? Take the scheme for building toilets. The shiny new toilets are there, but there’s no water and these aren’t dry lavatories. So how will they work? But people still hope.

Q. What took you there the first time?

I was on holiday in December 1999 with two school friends, staying in a village near Jodhpur. Next to our guest house, children were studying on the roof when I saw a teacher beat a young girl student quite violently with a stick. I wished to intervene but my friends dissuaded me as we were going to leave. When I came back to Delhi, I proposed a photoessay about what it’s like being a girl in a village school. ‘But what’s the news peg?’ I was asked. [Gill was then a photojournalist.]

Q. The pressure to contextualise is the pivot of everyday journalism…

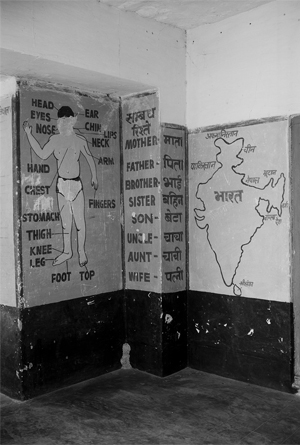

Well, also sometimes to have a preset narrative. I then decided to take a sabbatical and travel through Rajasthan to document village schools. I was travelling on my own—with a self-made map of government schools, Rajiv Gandhi pathshalas, marushalas (desert schools), experimental schools like Digantar—across the state through Jaipur, Baran, Barmer, Bikaner, Jaisalmer… some of those early pictures of the drawings on school walls are included in ‘The Mark on the Wall’.

Q. These photographs sometimes unmask cultural prejudices.

The drawings were made by teachers, local artists and children themselves to study or impart learning, so they are not art for art’s sake. Look at this photo (see on page 81), listing the words that make a family. A friend recently pointed out that the wife is ranked at the bottom [laughs]. Everything comes through. What is deemed of value, what are you teaching? The title ‘The Mark on the Wall’ is drawn from Virginia Woolf’s short story, where a woman gets obsessed with a mark on the wall, and what it might mean.

Q. But that work didn’t end up on the pages of a magazine.

No, I only came away from the experience with more questions than answers, and a series of encounters with remarkable people. I made friends who are still in my life. For instance, while looking for a school near Barmer in a big dust storm, I came across a bunch of women huddled together over a corpse of a young girl. The women looked intimidating, no one spoke Hindi and I was pointed to the village nearby. The first home in it belonged to Izmat, who might have been the poorest person in the village in terms of money, but was and is a force of nature. She grabbed me by the arms and began to tell me everything that was wrong with the place. When I said I was from Delhi, she urged me to return and tell all of it to Sonia Gandhi [this was in 1999]. She had had a terribly difficult life, her husband had abandoned her and her two young daughters and remarried, but she was unbeaten and utterly compelling. In a better world, she would be in politics because she had experienced it all first hand. She took my address and started to write me letters. Being there on my own, without any particular agenda, I could follow my instincts and the people I met freely. I quit journalism a year later, and funded my independent photography through teaching.

Q. Your first showing at Gallery Nature Morte in Delhi was 11 years later.

I knew so little of the world outside the cities. I guess, like Alice, I fell through the looking glass and, at some point, the journey itself became infinitely interesting and complex. It involved real people. I was worried that showing the work would change everything, especially my relationships with my friends. And on some days, I was cynical about what the photographs could achieve. But others were not. If a particular year happened to be the year of the drought, people would take me everywhere to document what was going on, to be able to show the world. They had this faith.

When I was contemplating my first exhibition in Delhi, they said, ‘Ismey bura kya ho sakta hai, bhala hi hoga. Log dekhenge, samjhenge’. It’s this belief that people have in the image, that it can change something. To retrospectively make sense of what I had created was much harder than making it. Because I began without preconceptions, there was no one theme. There are distinct narratives within the work. The series as a whole is called ‘Notes from the Desert’ and ultimately I see it as a series of books, each one a ‘note from the desert’. The first book was Balika Mela [in 2012].

Q. What was Balika Mela all about?

It’s a mela (fair) for rural teenage girls organised by the NGO Urmul Setu. I first photographed it in 2003, in its heyday. The girls would spend three or four days there, many of them leaving their homes without their parents for the first time. They were sent with a responsible person from the village or with a field worker from Urmul. There would be ferris wheels and puppeteers, magic men, shops… so many friendships were forged in this new free space. I would often stay at Urmul, and they would ask me to do something, so one year I decided to create a photo stall, a kind of homage to the local studios that I was inspired by. In 2003, there were no cellphones and many girls had never been photographed. I thought I would offer each girl a print. Initially, the girls were unsure, but soon they took over the stall and started posing and having a lot of fun. I don’t know where the gestures came from. But I think there is strength in that assertion, the desire to express and describe oneself.

Rajasthan can be a deeply violent and patriarchal state. There is a high incidence of young women being burnt, of girls committing suicide—and often that is only a cover up for murder. But isn’t it interesting how women also subvert or overcome their circumstances? Many of the women, like Izmat, have had a long and difficult struggle. At the same time, she is also unbowed in some sense.

Q. Your landscapes—‘Places, Traces’, the second in the series—are poignant, a song to the bareboned-ness of the lived, especially the graves.

People have made these graves with their own hands. The mounds are sometimes so subtle, and yet monumental. Then all these other things in or upon them, the cups and plates from homes, the personal artefacts, the hand-carved names on the gravestones, all punctuated by the holes that animals have burrowed. I’d go along with friends when they went there to pray, to light incense or water the graves, and look at the shapes and wonder at the stories. The presence —or trace—is so strong, and yet light. Someone commented about them being dark pictures, but I don’t see that at all.

Q. There is this whole Sufi thing about the desert being a spiritual place.

It is a landscape beloved to me. I find it uplifting. Sometimes there’s nobody around for miles. The scale of that space alters one’s perspective; even one’s sense of time is impacted. I set out to understand something, but I am still grappling with what this thing is. I don’t know if the work or the photographs can match it.

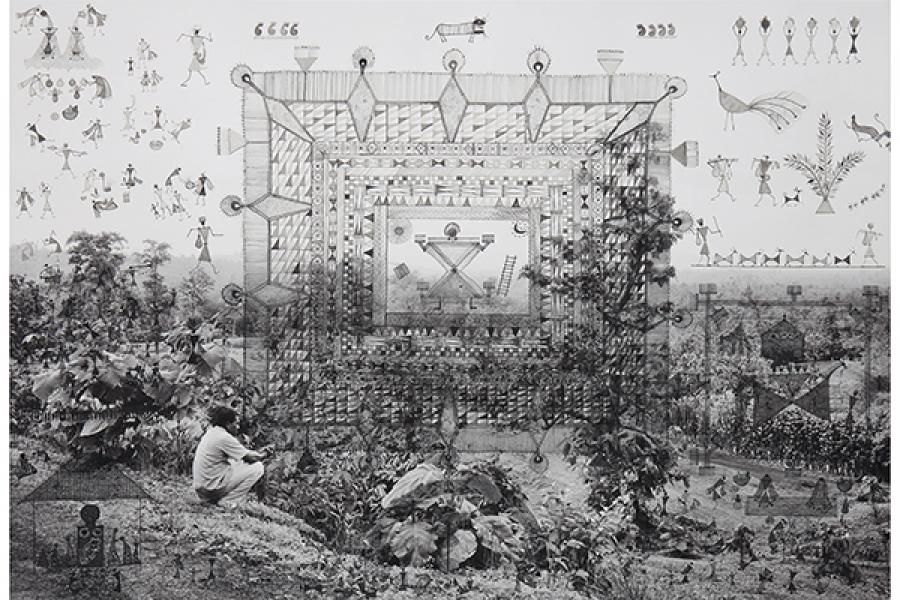

Q. The last of the series in your show, ‘Fields of Sight’—a collaboration with Rajesh Vangad, a Warli artist from Dahanu in Maharashtra—over the last three years is a turnaround of sorts, this act of painting on photographs.

In 2013, I was invited to do a residency at a school in an adivasi village in Dahanu. I made portraits of the children, which were exhibited in the school. I was staying at Rajesh’s home, who was a participant too. The Dahanu landscape is so green and idyllic, with rolling hills, close to the sea, and walking around, I started to photograph it for myself. But speaking to Rajesh and hearing his rich stories about the place, it struck me that I didn’t know it at all. I was photographing it simply as a landscape, in isolation, separate from those who inhabit it. I wished to bridge that distance. I began with photographing Rajesh in the landscape—as if we were constructing a personal map of places significant to him. But we ended up with images of him in the landscape, in the present moment. They were flat in a way, missing a dimension. One couldn’t see what he had known there. So I proposed an equal collaboration, in which I offered him my pictures to draw upon, to make apparent that memory. We wondered if we could connect the contemporary language of photography with the ancient art of Warli.

Q. The photos have an aboriginal feel to them, as if they were done in an act of dreaming.

That is a lovely thing to say, in the sense that dreams open up new dimensions. I started to think, how much of what we see is actually who we are… what we know is that what we project is what we see, no? What I see and what Rajesh sees might be two different worlds. Do any of us ever see the same thing? That’s why the series is called ‘Fields of Sight’.

The first set of works was completely narrative, very much about real things, like the year when a political party raided the village. Then the work started to get more abstract. The ‘Sweet and Salty Sea’ is about birds that are drawn to the sea, and how the sea is both a destroyer and nurturer. ‘Heaven and Hell’ depicts a perfect world that is destroyed when it stops raining forever. There is a never-ending forest (‘A Forest of Trees’), or ‘Gods of the Home and Village’, which is a sacred map of all the different times at which the gods are invoked. There’s a work about ants, who are revered for their industriousness in adivasi culture, which is why The Great Serpent lives in the Home of Ants. About people migrating to the city, about rain, Mahadev and Parvati spinning their eternal web… our monkey ancestors.

Q. All the awareness that is born of a communion with nature…

Look how Rajesh lives in his house in the village, surrounded by family, pets and animals, working in a room next to the kitchen with all the interruptions. He works amidst all this. He is so embedded in the ecosystem. It’s quite different from our whole notion of privacy and walls and shutting out. I don’t mean to romanticise anything, but in our attempts to escape and self create, we might have lost the vital bonds and dependence on each other that one sees in the village.

Q. All the sensitivity that we lose in our great rush to urbanise.

Yes, including the myths that come out of the sensitivity. One Diwali, Rajesh was living in my studio in Delhi. He did a special puja, and at one point, he opened out all the cupboards. Objects have a life too and so everything needs to breathe on auspicious days. We can be so thick, we think we are separate and immune which is a kind of arrogance really.

Q. The folk and tribal artists: We didn’t value them enough until the foreign collectors began showing them.

But even now, false distinctions are made. ‘Why is my work not in the contemporary art world?’ Rajesh asked me. Why qualify his work by calling it folk and tribal? But you know photography too was not quite seen as art for a long time—and is still only a new entrant in India. We have to stake claim to those spaces.

(This story appears in the July-Aug 2016 issue of ForbesLife India. To visit our Archives, click here.)