How India's regional cinema is breaking boundaries

Content-driven regional films are no longer isolated by language. The involvement of established Bollywood names and top studios has even taken them overseas. Take Marathi cinema, for instance

Shwaas, directed by Sandeep Sawant, won the National Award for Best Feature Film of 2003 and was also India’s official entry to the Oscars in the Best Foreign Language Film category in 2004.

A combination of good storytelling, a receptive audience and strong backing from established names such as Chopra has seen regional cinema flourish in recent times and make an impact on the world stage. India’s latest selection for the Oscars, the Tamil film Visaranai (2015), for instance, is the fifth regional film in the last ten years to be chosen to represent the country. Of the remaining four, two are in Marathi—Harishchandrachi Factory (2009) and Court (2015)—one in Malayalam—Adaminte Makan Abu (Abu, Son of Adam, 2011)—and the other is the Gujarati film The Good Road (2013).

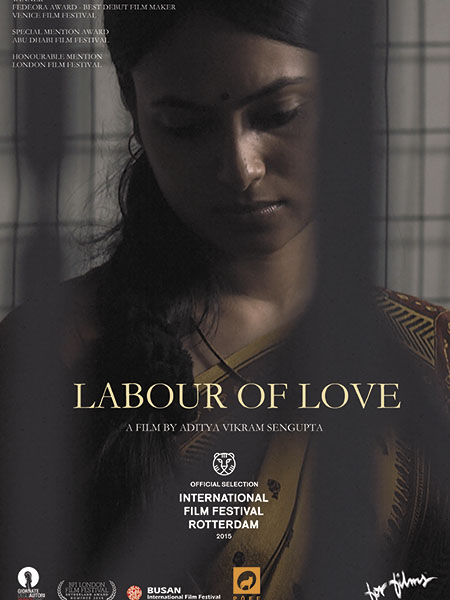

There’s more. Only recently, Raam Reddy’s Kannada film Thithi (2016) won the Best Film and Best Script Writers awards in the Asian New Talent Awards at the Shanghai International Film Festival. This came on the back of a National Award for Best Feature Film in Kannada for Reddy’s directorial debut as well as two top awards—Pardo d’oro Cineasti del presente Premio Nescens and Swatch First Feature Award—at the Locarno International Film Festival. A Punjabi film, Chauthi Koot or The Fourth Direction, by Gurvinder Singh, debuted at the Un Certain Regard section at the 2015 Cannes Film Festival and also won the Singapore International Film Festival Silver Screen Award for Best Asian Feature Film in December 2015. The 2014 Bengali film Asha Jaoar Majhe (Labour of Love) premiered at the 71st Venice International Film Festival in 2014 where it won the Best Debut Director award for filmmaker Aditya Vikram Sengupta and also received honours at the Marrakech International Film Festival and Abu Dhabi Film Festival in the same year.

Marathi film industry insiders believe the freedom to tell real stories without falling prey to the trappings of commercial cinema augurs well for films made in various Indian languages. “In Marathi cinema, you can tell stories from your heart. It has no binding of big economics involved in Bollywood projects. We have a star system and no matter what you say, we cannot escape that. You are not bound by a formula or the need for a star in a regional film. So the investment is less. It lets you tell the story that you feel for passionately,” Mapuskar tells ForbesLife India.

Actor Sandeep Kulkarni, who played an affable doctor in Shwaas and was the lead protagonist in the Marathi film Dombivli Fast (2005) which was screened at the London Film Festival in 2006, feels regional cinema connects to life and hence people from anywhere can relate to it. “Regional cinema is always rooted to reality; it is about that region, its culture, language and relationships. The culture may be different in different parts of the world, but life is the same everywhere. If you talk about that, you connect straightaway,” he says. But it’s easier said than done. Films in local Indian languages have been made since time immemorial but it is only now that an outpouring of new ideas has infused new life into them and revived interest, both at home and overseas.

Actor Shreyas Talpade who produced the successful Marathi film Poshter Boyz (2014), which is now being remade in Hindi, attributes three factors for the growing success of regional films. “The first is that there is greater awareness today as a result of which people have started flocking to the theatres. Earlier, people would make films, but there would be no marketing or publicity. The second is what has always worked for South and Hindi films—the youth connect. In the South, it was cool for a young couple to watch a South Indian film on a date. Till now, the Maharashtrian youth was not kicked about watching films made in their mother tongue. Now, with different types of films being made, they are embracing the quality stuff being offered to them. The third is the subject. With a new breed of filmmakers coming in, they are exploring newer ideas and providing something of substance,” says Talpade.

Marathi films have created believable stories on screen with a dash of humour and drama. The biggest example of this is the 2016 blockbuster Sairat—made on a budget of Rs 4 crore—which has become the highest grossing Marathi film to date with box office collections of close to Rs 100 crore. The film, produced by Zee Studios, became the first Marathi movie to enter the uncharted territory of Rs 50 crore and the numbers kept swelling thereafter. Director Nagraj Manjule’s tale of a rich girl and a poor boy caught in the clutches of caste and class, with song and dance adding to its mainstream appeal, has been a phenomenal success globally as well. It premiered at the Berlin International Film Festival in 2016 and is now being remade in Kannada, Telugu, Punjabi, Malayalam and Tamil. Filmmaker Karan Johar has brought the rights for its Hindi remake. All this feels surreal to Manjule, the son of a construction worker from Karmala in Maharashtra’s Solapur district. “I had no idea about the magic it would create at the box office, but I had faith in my film and was certain that people would like it. The response at Berlin was unbelievable and that reaffirmed my faith in my project. The fact that a foreign audience could relate to the story of two youngsters in a remote part of Maharashtra gave me a lot of confidence,” he says. Manjule, who also directed the acclaimed Marathi film Fandry (2014), feels Marathi cinema has evolved considerably and there is greater experimentation involved which adds to its flavour. Case in point: The Nana Patekar-starrer Natsamrat (2016) which made the maximum money for a Marathi film before Sairat broke its record. And other recent successes like Court, Killa (2015), Katyar Kaljat Ghusali (2015) and Timepass (2014).

What has also helped in building the momentum is the involvement of mainstream names like Chopra, Talpade and actor Riteish Deshmukh, who made his debut in Marathi films with a double role in the super hit entertainer Lai Bhaari (2014). “A big name getting involved adds credibility and results in a lot more people coming to watch the film. It also makes us responsible in a way because our name is associated with it, so we strive to do something worthwhile,” says Talpade whose Poshter Boyz earned over Rs 8 crore against a budget of Rs 2-2.5 crore.

Mapuskar concurs, but says there is no substitute for word-of-mouth publicity, irrespective of how much you market a film. “Our audience is matured and once they know the content, they come to the theatres. And for Marathi films, typically, there is no business in the first weekend. It picks up gradually. This is exactly the opposite of how Hindi films work,” he says. The Ventilator director, however, admits that with the likes of Priyanka Chopra coming into the picture, there is a greater enthusiasm towards work and people’s outlook towards the project changes. “I admire her and her mother [Madhu Chopra] for supporting regional cinema despite having the power and resources to back mainstream [Hindi] films. Writers and producers also feel enthused about the project. It benefits us commercially too.”

Kulkarni, at the same time, believes Priyanka Chopra too has benefited from the venture. “A good producer believing in a subject is a good sign. But it’s also a smart move because the investment is less in regional cinema. The risk is low and you get big returns apart from status and money,” he says.

Having said that, he admits that the impact of adding Chopra’s name to a film cannot be underestimated. “If an individual producer was involved, he may have probably cut corners to save costs and may not have backed the film to such an extent. Given her international appeal, she could have backed any Bollywood film, but credit to the director that she agreed to produce the film. Priyanka also acted in the film and it was integrated so well that it did not look forced.”

The economics that Kulkarni talks about can be understood from the example of, say, Shwaas which was made on a budget of Rs 65 lakh and earned Rs 2.75 crore at the box office. Ventilator was shot in 34 days as opposed to the three months that a Hindi film usually takes. “When we made Shwaas, the average cost of making a Marathi film was in the Rs 15-20 lakh range. We were surprised with the budget shooting up exponentially, but it was the need of the hour. Else, your work gets affected,” says Sandeep Sawant, director of Shwaas, which became the first Marathi film to win a National Award after 50 years. “The advantage of being involved in a regional film is the budget. It’s very limited considering that the market is limited. However, now with a film like Sairat doing roaring business, you know the capacity of the market. So if you make a good film, the returns are definitely higher. The risk is small, sometimes nil or negligible compared with Hindi films,” says Talpade.

It is therefore not surprising to see Bollywood throwing its weight behind Marathi cinema with actor Akshay Kumar’s Grazing Goat Pictures producing 72 Miles - Ek Pravas in 2013, director Sanjay Leela Bhansali backing Laal Ishq (2016) and Shah Rukh Khan and Rohit Shetty coming together for a film to be helmed by Duniyadari (2013) director Sanjay Jadhav. Chopra has already produced a Bhojpuri film, Bam Bam Bol Raha Hai Kashi (2016) and a Punjabi film Sarvann, scheduled to hit screens this January.

Global names like Fox Star Studios India are now showing an interest in regional films

It’s a lucrative industry not only for those associated with Indian films. International studios are showing interest in regional cinema as well. Fox Star Studios India, for instance, made its foray into the Marathi film industry with the 2016 film Half Ticket.Today the industry is more organised and commands greater respect, but regional cinema has attracted established names even when there was a limited structure in place. Actor Sonali Bendre played the lead in Amol Palekar’s Anaahat, which received the Best Artistic Direction Award at the first World Film Festival of Bangkok in 2003. And Nandita Das has been a regular feature in films in various Indian languages, including Chitra Palekar’s directorial debut Maati Maay (A Grave-keeper’s Tale, 2006) in Marathi. The actor says she’s surprised when people question her choice of doing “obscure films”. “For me, doing a Kannathil Muthamittal (2002) in Tamil or an Aamar Bhuvan (2002) in Bengali was just as fulfilling, if not more so, than doing a film in Hindi. The criteria of choosing a film remain the same, irrespective of the language. It is invariably the script, the director and the role, probably in that order. I have enjoyed being in films made in different parts of the country, as they are more rooted, and being less pressured by commercial factors, less prone to compromises. There are stories to be told, there is talent to be explored and a cultural ethos to be learnt from, in all of these regions,” says Das. The trend continues: Vivek Oberoi will be seen in Riteish Deshmukh’s next Marathi venture, Vidya Balan featured in Ekk Albela (2016), Tisca Chopra starred in Umesh Kulkarni’s Highway (2015).

The stories may be local in nature but their reach is beyond boundaries. The success of regional films internationally is evidence of that. Most filmmakers agree that global recognition gets them more eyeballs and it’s gratifying that their films reach an audience that does not understand the language the film is made in. “Taking your film with local subjects to cinema lovers and getting a response from them is a rewarding experience. The fact that such cinema can reach legions of cinema lovers is commendable. Eventually, the screenplay is the hero,” says Sawant, whose Shwaas had over 20 shows in the US in two-and-a-half-months after it was nominated for the Oscars. “It’s hard to put that experience into words. The audience was blown away by the film. Initially, I was apprehensive about the fact that it’s a Marathi film and whether it will reach the audience even though it has subtitles. But there was no problem.” Kulkarni adds, “International recognition is important. World cinema or regional cinema connects with people in different parts of the globe and the audience gets to see it. It obviously results in monetisation and recovery.”

In India, an improved movie-going experience thanks to the mushrooming of multiplexes and enhanced sound and picture quality has also resulted in people coming to the theatres in droves to watch regional cinema. And the audience is no longer bound by the language barrier. Talpade and Kulkarni both say that many non-Maharashtrians are now watching Marathi cinema and that they constitute a healthy chunk of the movie-watching crowd. Mapuskar concurs: “The audience is receptive to good films, especially the non-Marathi crowd.”

There’s a push from state governments too that should spur filmmakers to come up with more content-driven films.

Last February, the Gujarat government introduced a gradation system for providing financial assistance to Gujarati film producers that will range from Rs 5-50 lakh. The Maharashtra government in April 2015 made it mandatory for multiplexes to screen at least one Marathi film between noon and 9 pm. The film fraternity sees this as a welcome sign. “It’s good that the government has come up with this move; it can create a plus point,” says Sawant. Kulkarni says it was the need of the hour as the business is blossoming. “The government’s support is vital, but it also woke up late. There has been a change now. This is a result of everyone’s effort from Shwaas till now,” he says.

No need for a ventilator here. Regional cinema is not just alive, it is in the best of health.

(This story appears in the Jan-Feb 2017 issue of ForbesLife India. To visit our Archives, click here.)

Post Your Comment