The history and mystery beyond Vegas

The casino town is only half the story of Nevada. The loneliest road in America is the other

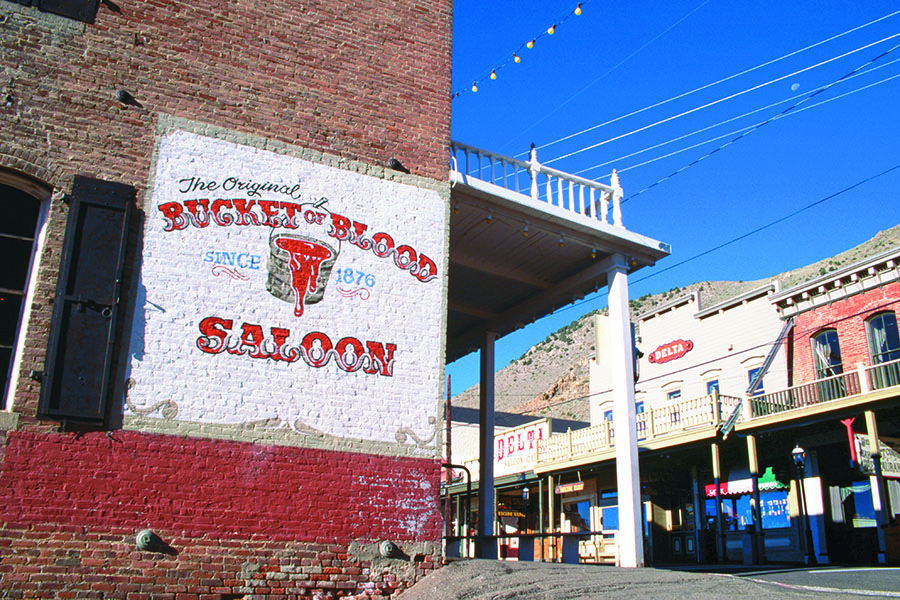

This Virginia City pub’s name, ‘Bucket of Blood’, is a reference to the blood that’s mopped off the floor after a fight

Image: Stephen Saks / Getty Images

The colours and chaos of Vegas disappeared rather quickly and suddenly when we turned into the highway leading out of town. In contrast to the bright lights and buzz, we were surrounded by arid desertscape. And that’s how it continued for about two hours till we stopped to stretch our legs at a grocery store on the highway, in the tiny settlement of Crystal Springs. There, I found myself staring at some graffiti on the walls of the parking lot.

This rather long painting was a montage of alien activity. It had a UFO landing on one side and a stagecoach filled with gun-toting green aliens on the other. Not entirely out of place as this was an area famous for being the hub of extra-terrestrial activity in this country.

The road ahead was forked and caught me in two minds. One would lead me further into State Route 375, popularly known as the Extra Terrestrial Highway, and into the heart of Area 51. This was where the US government allegedly had a top-secret base researching the movement of UFOs and aliens in the country. Area 51 was also where, as conspiracy theorists claimed, the country faked moon landing photographs in 1969 to go one up on arch-rival Russia.

But I had to forgo that for now. Because, the other route, my original plan, was the equally intriguing Route 50, one that would take me to semi-deserted mining towns and fabulous state parks.

Route 66, which connects Chicago with Los Angeles, has enjoyed iconic status in American history, finding a place in literature and pop culture. Remember Nat King Cole’s hit song ‘Get your kicks on Route 66’, or John Steinbeck’s nomenclature for it as the ‘mother road’ in his Pulitzer-winning book The Grapes of Wrath? The one we were driving on was its lesser-known cousin and cut through the country over 4,840 km, from Ocean City in Maryland to Sacramento in California. And the Nevada portion of this road, on which I was standing, is known as the ‘loneliest road in America’, as a travel writer from Life magazine had put it in 1986.

I suspect there are far emptier roads in the heart of the country. But the sense of desolation that grips some of the places we passed on this journey was poignant. Consider that these were not always the one-horse, one-main-street towns they are today. Located on the historic gold route of the West, they were once prosperous and populous, attracting the brave and curious at the height of the Gold Rush in the mid-19th century. Once the gold dried up, these towns also lost their relevance.

Pioche, which, in the mining heyday, proudly claimed to be the ‘baddest town in the bad West’

Pioche, which, in the mining heyday, proudly claimed to be the ‘baddest town in the bad West’Image: Witold Skrypczak

We encountered the first of these towns at Pioche, just before we were to join Route 50. Pioche was the kind of town I had only seen in old Westerns. It had one arterial road, lined with saloons (pubs), cafés, grocery stores and even an opera house. You could almost picture James Dean walking out of one of the buildings swinging his hardy pistol. But the only two humans I saw emerged from one of the saloons. They wore long-sleeved shirts with broad cheques, bootleg jeans, calf-length leather boots and Stetsons, looking straight out of the casting company Central Casting.

At lunch later, I asked my waitress Jeannie about the population of that town. “They say 800, but I don’t know where they keep all o’em,” she answered dryly. Jeannie herself had lived in this town for nine years but was still considered an outsider. And she was that rare person who moved into Pioche, in search of a job, instead of out.

In the mining heyday, this town of over 9,000 people proudly claimed to be the ‘baddest town in the bad West’, allowing residents to shoot any stranger at sight in order to guard their own mines. Things were so bad, records say, that 72 people died in such fights in the early 1860s. “Well, it’s the only thing they had,” shrugged Jeannie, referring to the mines.

The situation was more or less the same in the other towns we crossed or stopped at for refreshment breaks. Eureka, Austin, Fallon: They were all tied together by their tragic history. But the locals still managed to pull out a warm smile, snide remark or an engrossing tale about how they kept themselves busy when the gold was gone.

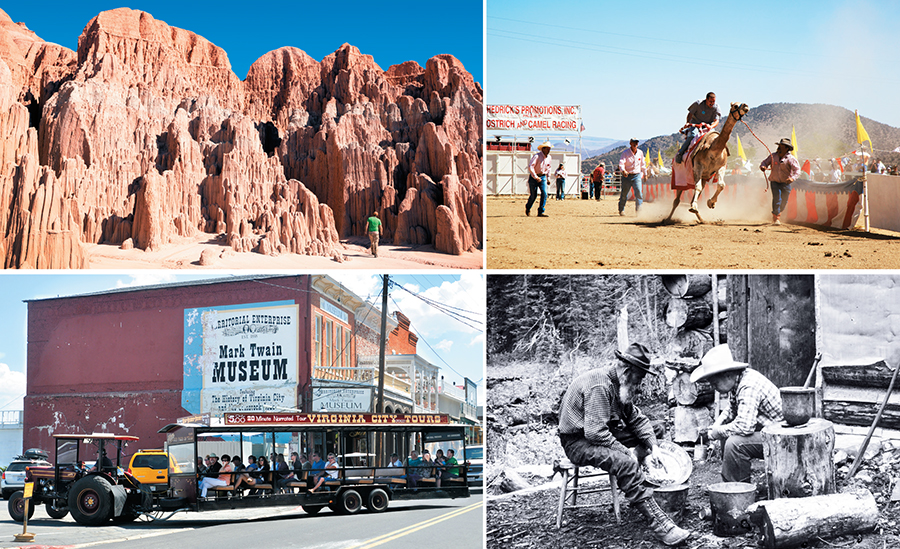

Clockwise from left: Cathedral Gorge State Park; the annual camel race in Virginia City;the Gold Rush in the mid-19th century; the building where Samuel Clemens first signed his byline as Mark Twain in Virginia City

Clockwise from left: Cathedral Gorge State Park; the annual camel race in Virginia City;the Gold Rush in the mid-19th century; the building where Samuel Clemens first signed his byline as Mark Twain in Virginia CityImages clockwise from left: IrinaK / Shutterstock.com; Kevin T. Levesque / Getty Images; Everett Historical / Shutterstock.com; Getty Images

Aside from its disturbing history, Nevada can also be quirky. Take the annual bathtub races, a ritual that I heard of during my night halt at Ely. Started by a local in 2009 and drawing over 5,000 visitors every year, this race takes place on the placid waters of the Cave Lake with bathtubs repurposed as boats. The event has recently been listed by the American Bus Association as one of the top 100 events in North America. Says a local, “Some fall, some float, only a few manage to make it across the lake.”

Just over 300 miles away, in Virginia City, closer to the California border, locals let their camels and ostriches loose in a similar annual event. What was originally a story cooked up by a bored journalist—of a fictional race of camels—has now become one of Nevada’s star attractions.

Virginia City is a personal favourite too because this was where Samuel Clemens of Missouri first signed his byline as Mark Twain some time in the early 1860s. Clemens moved to this wealthy mining town in search of his own pot of gold before giving up those dreams for the job of a reporter in the local newspaper. The building where Mark Twain was reborn as Samuel Clemens is now a small museum housing printing paraphernalia from his times, among other things.

Almost everyone in Virginia City seemed to run a pub or a souvenir shop. And with its taste for the macabre, Virginia City could well be a poster town for the Wild Wild West. Consider the name ‘Bucket of Blood’ for a pub, a reference to the blood that’s mopped off the floor after a fight. Or the iconic exhibit of the famous ‘Suicide Table’ at another pub, where gamblers regularly shot themselves after losses in card games. Or the mock gunfights at a makeshift stadium or shops selling posters of men brandishing rifles with punchlines that say ‘Here, we don’t call 911’. Has much changed in the town since Mark Twain lived here? I doubt it.

This road trip had been one delightful discovery after another, not just for the string of ghost towns along the way but also the natural wonders. A few hours from Vegas was the Cathedral Gorge State Park, a high desert park that got its name from mini hills that were shaped like cathedral spires.

When we entered the gates off the main highway, there were no other visitors; just a ranger to show us around. And a sprawling landscape of cliffs and spires carved into stunning, dramatic shapes by millions of years of volcanic activity and water erosion.

Our ranger led us into a narrow trail deep inside a complex network of caves and cliffs. Red and yellow bentonite clay canyons towered over us on all sides as we squeezed our way through. The landscape was stark and dry, except for the occasional green shrubbery to break the brownness, and the changing hues of the rocks with the interplay of sunlight and shadows—from deep brown to a light pink. “It’s over 2,000 acres of such landscape but most visitors hardly manage to scratch the surface of this park,” the ranger said.

Eight thousand year old rock carvings done by Native Americans at Grimes Point Archaeological Area

Eight thousand year old rock carvings done by Native Americans at Grimes Point Archaeological AreaImage: Witold Skrypczak

Another day, close to Fallon on the western side of Route 50, we took a break to explore Grimes Point Archaeological Area, where Native Americans have left a large open space scattered with giant boulders containing petroglyphs (rock carvings). This site, over 8,000 years old, is still considered sacred by the local community of Native Americans.

While a few of these carvings depict familiar natural phenomena like the sun and snow, most have not yet been deciphered. And amid these rocks, I came across one with a remarkable similarity to the ‘Om’ symbol. My guide, Donna from the Paiute tribe, shared stories of how white explorers first came to this area and took it over from the original inhabitants. The symbol was perhaps a reference to their history. I showed Donna the identical Indian version. “Perhaps all great ancient cultures had some similarities,” she said. I couldn’t agree more.

My final halt in Nevada before entering California was at Genoa, a small town at the base of the Sierra Nevada mountain range. While its attraction for most tourists is its proximity to Lake Tahoe (famously described by Mark Twain as ‘the fairest picture the whole world affords’), what I loved was a solo performance by a local actor. Dressed in leather boots, a wide hat and a patch over one eye, Kim Copel narrated the colourful life story of Charley Parkhurst, a stagecoach driver during the Gold Rush era. Only upon his death in 1879 was Charley’s big secret revealed—that he was actually a woman dressed as a man, to make a living. Not only had this lady fought bandits with the best of her peers, but she had also managed to vote for Ulysses Grant in the American Presidential elections of 1868 (over 50 years before women were given the franchise in the country).

When I finally left Nevada, I could only think of one word, which I had come across at a small souvenir shop somewhere on the way, that defined the spirit of this state: Nevattitude.

(This story appears in the Nov-Dec 2016 issue of ForbesLife India. To visit our Archives, click here.)

Post Your Comment