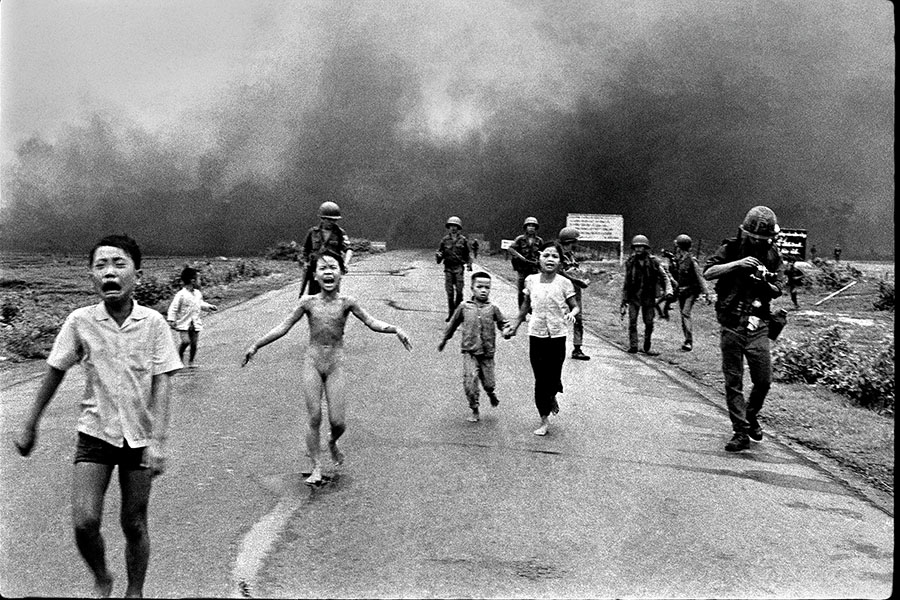

I took the picture that changed the war: Nick Ut

Award-winning photographer of The Napalm Girl talks about putting people at the core of his work, and his coverage of the Vietnam War

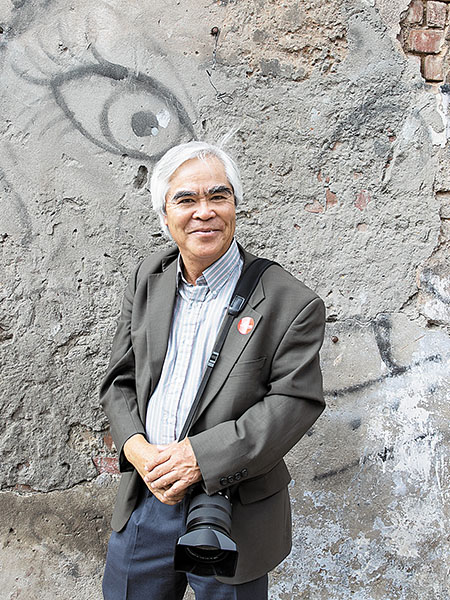

Nick Ut’s photograph, called The Napalm Girl, changed world opinion on the US’s involvement in the Vietnam War; Ut, in New Delhi, on a recent visit

Nick Ut’s photograph, called The Napalm Girl, changed world opinion on the US’s involvement in the Vietnam War; Ut, in New Delhi, on a recent visitImage: Nick Ut

Sometimes, a single moment can define an entire era. For the Vietnam War, which lasted 20 years between 1955 and 1975, that moment was photographed by 21-year-old Huỳnh Công (Nick) Út outside the village of Trang Bang, about 40 km northwest of Saigon. On June 8, 1972, Ut, a photographer with Associated Press, saw a handful of terrified children running his way from their village that had just been bombed by napalm by a South Vietnamese aircraft. Among them was nine-year-old Kim Phuc, screaming and naked; she had ripped off her burning clothes.

After clicking the photograph, Ut rushed to save Phuc—she had suffered third-degree burns on 30 percent of her body from the bomb that can create temperatures between 800 and 1,200˚C—and took her, and the other children, to a hospital. His actions saved her life, and made them life-long friends.

Ut’s photograph, called ‘The Napalm Girl’, became representative of the atrocities of the Vietnam War—the napalm bombing could be categorised as ‘friendly fire’, and Phuc collateral damage—and joined Malcolm Browne’s ‘Burning Monk’ and Eddie Adams’ ‘Saigon Execution’ as defining images of the brutal conflict. In 1973, it won every major photography award—the World Press Photo award, the Pulitzer Prize (Ut is the youngest winner), the George Polk Memorial Award and the Overseas Press Club award. Two years later, US President Gerald Ford announced an end to the war and all US aid to South Vietnam.

On a recent trip to India organised by Leica Camera, German premium camera manufacturers, 67-year-old Vietnamese-American Ut—he was holding a Leica when he clicked ‘The Napalm Girl’—spoke to Forbes India about the changing nature of war photography and what happened on June 8 outside Trang Bang. Excerpts:

Nick Ut, photographer of the Napalm Girl

Image: Madhu Kapparath

Image: Madhu Kapparath

Q. In your career as a photojournalist, you have covered wars, celebrities and sports. Is there a favourite you have among these subjects?

It is just my job. But I love taking pictures of people. During the [Vietnam] war, I was in Vietnam, Cambodia and Laos. I would take pictures of people, and what they have lost. After the war, I was in Tokyo for two years, when I photographed politics, business and sports, such as sumo wrestlers.

Then, when I went to America [in 1977], I was worried. Because I did not know anything about America. Then I began to shoot hockey, baseball, basketball… they are all American sports, and I could not say no.

When I arrived in the US, I didn’t know anything about Hollywood; I would just watch the films. And then suddenly I was photographing people like John Wayne and Greta Davis, and I would think to myself, ‘My God, I saw their movies, and now I am taking pictures of them’. Being in Hollywood is crazy; although I love Hollywood. Because of The Napalm Girl photograph, everybody knows who I am. The movie stars know me, and ask me to take their pictures. They say, “Nick we know you… you covered the war.”

Even when I covered US President Donald Trump, he pointed to me and said, “I know who you are.” But when I took a picture of myself with him, and put it up on Facebook, a lot of people told me, “Why him?”

Q. What is it that you look for when you take photographs?

Every time I go on an assignment, I look for a story. I don’t start clicking pictures right away, I focus, look around for something happy or sad.

One of the best stories I covered was that of OJ Simpson, and Michael Jackson. Simpson was big in the history of America; there were hundreds of media people every day outside the court house.

Image: Madhu Kapparath

Q. What are your views on war photography?

Most countries don’t like journalists in conflict areas. So many journalists have been killed in Syria and Iraq. One of the best photographers was Anja Niedringhaus from Germany, who worked for Associated Press. She was a Pulitzer Prize-winning photographer. She had covered the Iraq war, and was covering Afghanistan. [In 2014] she was in a car, with a reporter, when a policeman shot them. There was no reason to shoot them.

I have a lot of photographer friends who want to go to war. But nobody pays a lot of money anymore. I tell my friends that they should do another job. Why do you want to kill yourself?

Moreover, nowadays there is nothing much to cover anyway, because the government controls the media. When I was in Vietnam, I had full freedom. I could take pictures of everything, nobody stopped me from going anywhere. The Americans wanted to see what was happening in the war, see it in the newspapers, and on TV. But today, in Afghanistan, they completely control the coverage. I was going to cover Afghanistan, when a friend told me, ‘Nick, this is not Vietnam’.

I covered the first Iraq war for a month. By the time the second started, I was married and had children. I could not go to a war and die, and leave them alone. So, if you are going to cover war, you should be single.

Today journalists travel with the armed forces, even though America does not allow many journalists. Although it is safer for them this way, it also means that they don’t have access to anything that the military does not want to show.

Q. How much freedom do photojournalists have within the US?

The government controls the media a lot. If there is any incident, say a shootout, there is a lockdown over a 2-mile radius, and no mediaperson is allowed within it. So, if you want a good shot, you will have to fly over the area in a helicopter. I have to go to the top of tall buildings, with really big lenses to get photographs from almost a mile away. But you cannot get good pictures like that.

I want to show the loss that people have suffered, their faces. But you cannot go anywhere close to them. You don’t even get to see the bodies of those who might have been killed. When I moved to the US in 1977, it was not like this. But in another 10 years or so, things began to change.

Ut’s photograph of children being evacuated during the Vietnam War

Image: Nick Ut

Image: Nick Ut

Q. When you covered the Vietnam war, what did you look for?

I looked for pictures almost every day; of course there was the war, but I would look for action. Although I covered the war for almost 10 years, I never got a picture like the napalm bombing. I wanted to show the faces of people, and children. I would show soldiers.

Q. What effect did the war have on you personally?

After I moved to the US, I had a lot of problems. Till today, I am not able to watch war movies. If I see them, I get nightmares. I had to consult my doctor. He said, ‘But you are not a soldier. They fight every day’. I told him that I saw soldiers fight, and people every day, through my camera. I was wounded, in the left leg, stomach and chest. I am lucky to be alive, but [with] what I saw, I would die almost every day.

Q. What happened after you took the Napalm Girl photograph?

When I took that picture, I was really happy. Because it changed the war. After that picture was published, the world became angry about what America was doing in Vietnam. US President Richard Nixon saw it, and knew that they had lost the war. He said it was a fake photograph. But there was video footage of the napalm bombs coming down on the village, and I said you can talk to Kim Phuc.

I was also lucky that I could save Kim’s life. There are a lot of journalists who take pictures and then walk away. I knew that if I did not help her, she would die. There was smoke coming out of her body, it was so hot. I put her in the car; she sat on the floor, as she could not sit anywhere else because her skin was falling off. And she kept saying, “Brother, I’ll die, I’ll die.”

We drove for about 40 minutes to the hospital, and pleaded with the doctors and nurses to help. But they refused, because she was a local, and wanted me to take Kim to Saigon, which was two hours away. But I knew she would die in that time. So, I told the doctors that if she died, the news would be on the front page of all newspapers. Only then they agreed to help.

But, in the next few days, when the picture was out, the best doctors from Germany, Japan and France came to help Kim.

Q. How has photojournalism evolved over the years?

Today, all photographers and reporters have iPhones on which they shoot videos and send them first. Whether they work for newspapers, or TV channels, video is the fastest way to catch action. I also do the same. If you shoot on film today, it will take two days [to develop, print and transfer]. It’s too late. No one will want your picture.

In the early days, whenever I went on assignment, I would first set up a dark room in the bathroom of the hotel room. I would shoot one round, and send it right away, because you couldn’t wait too long. I remember I would work with negatives that were still wet, prints that were still wet.

Q. Do you miss doing that?

I love darkrooms, but I don’t miss doing that. Because it was too much work.

(This story appears in the 12 October, 2018 issue of Forbes India. To visit our Archives, click here.)

Post Your Comment