The vegan zeitgeist

A growing number of activists, startups and festivals are helping veganism spread across the country. But is it enough to trigger mass-scale adoption?

Kuntal Joisher stands atop Mount Lhotse, a peak he scaled not just on a vegan diet but with vegan clothing too

Kuntal Joisher stands atop Mount Lhotse, a peak he scaled not just on a vegan diet but with vegan clothing too

Image: Mingma Tenzi Sherpa

At 29,029 feet, Kuntal Joisher lowered himself into a crag and cried. “I couldn’t stop the tears, although I knew they could freeze my eyelids shut,” says the 38-year-old. After two failed attempts, he had finally conquered Mount Everest in 2016. “I called my father [with a satellite phone] and told him I was on top of the world,” he recalls. It was an extraordinary feat for more than one reason: Joisher is the first vegan to have ever scaled the iconic peak.

“It’s given me a voice to speak about veganism,” says Joisher. Slightly built and dressed in a cobalt blue ‘Go Vegan’ tee, the computer programmer cuts a modest figure, but inspires awe. “He can do anything,” gushes a 20-something vegan who follows his feats on Instagram.

And so it is. Veganism—the practice of not eating or using animal products—once considered weird and extreme, is now the height of cool, especially among the young and urban. Celebrity adherents from popstars Beyoncé and Miley Cyrus to politicians Bill Clinton and Al Gore, and even sporting greats Venus Williams, Novak Djokovic and, more recently, Virat Kohli, are upping its popularity. Supermarket shelves and restaurant menus boast vegan offerings, startups from Mumbai to Udaipur are selling meat and dairy alternatives, and vegan festivals are pulling large crowds. “The vegan movement is slowly gaining a lot more traction and turning into an industry,” says Palak Mehta, founder of online media portal VeganFirst. While numbers are hard to come by, she estimates that there are 20 to 30 lakh “vegan-curious” people in India—a term used to describe those who are considering the lifestyle but aren’t yet committed to it—while the purists would be “a couple of lakh” in number but growing fast.

*****

On his 45-day expedition to Mount Everest, Joisher insists his vegan ways weren’t a liability for his co-climbers or the Sherpa cooks who accompanied them. “Veganising the menu was easy,” shrugs the former lacto-ovo vegetarian. A typical meal in the mountains comprises rice and dal—about 75 percent of the plate, says Joisher—while the rest includes a portion of vegetables and meat. He replaced the latter with other pulses, nuts or an extra helping of dal. And for breakfast, while his crew wolfed down oats and milk, he mixed the cereal with water and nuts.

But he admits that he didn’t watch his nutrition as closely before taking to mountaineering. Joisher would load up on fried foods, chips and fizzy drinks in his initial few years of going vegan. “It’s technically vegan, but it’s not exactly healthy,” he says sheepishly. His weight burgeoned to 107 kg from about 70 kg earlier.

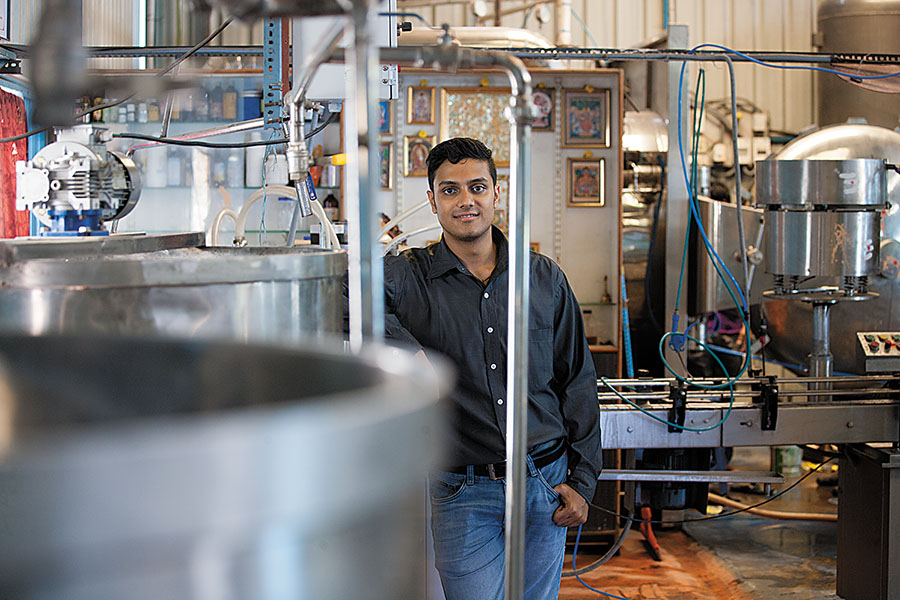

Abhay Rangan renamed his startup from Veganarke to Goodmylk to widen its appeal

Abhay Rangan renamed his startup from Veganarke to Goodmylk to widen its appeal Image: P Ravikumar for Forbes India

Veganism is touted to have three main benefits: Reduced animal cruelty, lesser environmental impact and, potentially, improved health. The first two reasons are well founded: Consider the wrongs of factory farming glaringly highlighted by popular documentares like Earthlings (2005) and Cowspiracy (2014). Cows are artificially impregnated every few months to produce milk, their calves taken away at birth and male ones, in particular, killed for meat. Mass-producing eggs also involves killing male chicks by throwing them into grinders. “There’s no difference between a piece of beef, a glass of milk and a leather good,” says Rohit Ingle, a vegan activist who cycled 8,000 km across India last year to raise awareness about the cause.

The environmental impact of animal farming is equally alarming. Eighty percent of the world’s farmland is used for rearing animals; an inefficient amount of grain, most of which is fit for human consumption, is used to produce meat—more than 10 kg of soya bean is required to produce 1 kg of beef, for example—and greenhouse gases are emitted in the process. According to the United Nation’s Food and Agriculture Organisation, the world’s ruminants—animals that acquire nutrients from plant-based foods—annually release 100 million tonnes of methane, a greenhouse gas 25 times more powerful than carbon dioxide. More farm animals means more wreckage to the planet.

But, as ethically and environmentally motivated vegans might be, is the diet really healthy? Do vegans get sufficient amounts of protein, calcium and nutrients like B12 that are found in meat and dairy? “Have you ever heard of anyone with a protein deficiency?” argues Dr Nandita Shah, a homeopath known for reversing diabetes and other lifestyle diseases through dietary changes, and founder-director of Sharan, a not-for-profit that helps people connect with animals and nature. She pauses before continuing, “Most of us eat more protein than we need… Besides, where do horses and elephants [herbivores] get their protein from?”

A food truck in Udaipur selling products manufactured by Good Dot, a plant-based meat startup

A food truck in Udaipur selling products manufactured by Good Dot, a plant-based meat startup Image: Aakash Aryan

Shah says that more than 60 percent of the global population struggles to digest milk because human intestines cease to produce sufficient quantities of the necessary enzyme, lactase. Hence, it’s a myth that milk gives us the nutrients we need, she adds. Elite vegan athletes like Djokovic and the Williams sisters, and even body builders such as German Patrik Baboumian, touted as one of the strongest in the world, further bust the stereotype that muscle comes from meat.

*****

Even though I scaled Everest on a 100 percent plant-based diet, I received a lot of flak,” admits Joisher. “Because the jacket I wore was made of down feather.” Mindful that down is harvested by killing ducks and geese in the “most gruesome fashion”, Joisher says he didn’t have an alternative. “No other clothing would protect me at those temperatures. Nothing was available in the market,” he says. On his blog he writes, “I am NOT the first #Vegan in the world to climb Everest.”

Six months after scaling Everest, he climbed Mount Lhotse, a 27,940-feet peak, also in the Himalayas. This time as a complete vegan. After being turned down by the largest winter clothing companies for a custom-made non-down feather jacket that would keep him warm and safe at high altitudes, Joisher contacted a small Italian company called Save the Duck. To his surprise, they agreed to make him a one-piece synthetic suit from recycled fishing nets. “It worked wonders,” he says, “shielding me from the wind gusts and biting cold.”

Cruelty-free products on sale at the One Earth Festival in Mumbai

Cruelty-free products on sale at the One Earth Festival in Mumbai Image: Ahimsafest 2017

Second-time lucky, Joisher doesn’t mind the diehard vegan community that disapproved of his Everest expedition choices. “I too was a militant vegan in the first two years of my journey. It’s only later that I mellowed,” he says.

Cyclist Ingle, similarly confesses, “After I turned vegan, I became an angry vegan because people around me weren’t changing.” Alokparna Sengupta, deputy director at animal protection organisation Humane Society International (HSI)–India, quips, “I would shove animal cruelty videos in front of my friends and force them to watch it. But that approach doesn’t help. It only puts people off.”

This habit of evangelising has given veganism a bad name, says Sengupta; as part of her work, she helps vegan business owners connect with investors and markets. Bengaluru-based Goodmylk, which offers non-dairy milk and yoghurt, is one such startup. On HSI’s advice, 21-year-old founder and CEO Abhay Rangan ditched the name Veganarke that he had started out with and rebranded to Goodmylk. “It helps widen the appeal of such products,” says Sengupta.

Samir Pasad, co-founder of VeganBites, a subscription-based vegan lunch delivery business in Mumbai, concurs. While the ‘vegan’ branding helps interested customers easily discover their service online, for their latest foray into non-dairy ice-creams they’re going with innocuous branding. “If we say vegan ice-creams it is limiting, because people immediately think it will not taste good,” he explains, adding that a deal with a large Mumbai-based retailer to stock their ice-creams is almost sealed.

In fact, even among the 180 to 200 takers for his daily tiffin service, only 10 percent are pure vegans. Says Pasad, “90 percent are not vegan, but health conscious.” So also with Goodmylk. “Contrary to what people think, the market isn’t small,” says Rangan. Only 30 percent of his customers are vegans, he says, while the remaining avoid dairy for health reasons or lactose-intolerance. “That’s a big market,” he points out. In the early days, his mother would make the products in their kitchen and he would deliver them on his moped. Today, Goodmylk has secured funding from a Texas-based investor, manufacturing is outsourced and 1.5 tonnes of non-dairy milk and curd are delivered per month in and around Bengaluru, up from 100 to 200 litres when they started out in end 2016.

Good Dot, a plant-based meat startup, similarly claims that the majority of their growth is coming from “meat reducers”. Abhishek Sinha, founder and CEO of the Udaipur-based startup that sells 10,000-15,000 units a day, says, “Everybody wants to eat healthy. If it tastes good and it’s priced right, they’re happy to make the switch.” That said, it’s easier to convince a non-vegetarian to try out mock meat; the word ‘meat’ in their branding, explains Sinha, often puts off a vegetarian.

While the number of fully-committed vegans might be small, this larger group of “reducetarians” or “flexitarians” who are trying to cut down on meat and dairy, or just trying to eat healthier, points to a larger trend towards caring about what we eat. And it’s that which businesses are capitalising on.

*****

In 2014, when Joisher was readying for his first attempt to climb Everest, he received news that 17 Sherpas, hampered by fierce winds, died while scaling the peak. He was forced to abort his climb midway. The next year, he tried again, but this time only to narrowly cheat death. Joisher had made it to the base camp when the 7.8-magnitude earthquake hit Nepal. Caught in a deadly avalanche, those just a “few feet” ahead of him got blown off by the rocks of ice, he recalls. By the time the snowslide struck him, much of its impact had been lost. “It was as though I was given a second chance at life,” he says. And it’s one that he didn’t lose, successfully summiting the following year.

Persisting is an idea that resonates with vegan business owners as well. The market is growing rapidly, but it’s small in absolute numbers, making scalability an issue. “But if you have the conviction and resources to stay the course then we’re at a tipping point,” says Good Dot’s Sinha, who, after being selected to serve his mock meat at the recently concluded World Parliament of Religions in Toronto is eyeing overseas markets. Back home, he’s already entered into 14 in-principle franchisee agreements to operate food trucks in major metros as well as cities like Surat and Patna.

The issue of scalability, high prices of certain vegan substitutes, especially cheeses and nut milks, and a lack of awareness are also challenges cited by Shammi Sethi, a real estate broker who set up Rare Earth, a “100 percent vegan store”, in Mumbai’s Khar in late 2016. He found it difficult to find vegan products once he made the switch, he says, prompting him to “do the right thing” and open a store. But breaking even has been difficult, he admits, even though he owns the property.

It is here that festivals showcasing all things vegan—six to seven have already taken place this year pan-India, according to VeganFirst’s Mehta—play a critical role. The largest of its kind, with 200 vendors and 5,000 expected footfalls, is the One Earth Festival, due to take place in Mumbai in early December. Now in its third edition, one of the aims of the festival, says Ruchika Chitrabhanu, a core member of the Ahimsa Parmo Dharma group that organises the event, is to “bridge the gap” between vegan businesses and the vegan curious. Satellite events such as cooking demonstrations are also conducted as part of the festival, which she says, are the “backbone” of the festival. “If you don’t educate people about what substitutes to use in their everyday cooking, they won’t be able to implement veganism.”

And while some might argue that high prices are a deterrent to adopting the vegan life—a litre of soya milk, for instance, costs ₹150 on average compared to ₹50 for cow’s milk, while nut milks cost a lot more— proponents reason that with a little bit of effort homemade versions can be made on a budget. Joshier says he buys soya milk powder for ₹45 and makes a litre of the mixture at home.

It might be a while before the Indian market matures, like it has in the West where large companies are snapping up alternative meat and dairy companies. Consider French FMCG giant Danone’s acquisition of soya-milk upstart Alpro last year, Tyson’s, one of the world’s largest meat producers, purchase of a 5 percent stake in veggie-burger maker Beyond Meat, or Unilever owned soya bean ice-cream maker Swedish Glace. “It’s a trend we will see happening here,” predicts VeganBites’ Pasad, “but it will be another five to 10 years.”

(This story appears in the 07 December, 2018 issue of Forbes India. To visit our Archives, click here.)

Post Your Comment