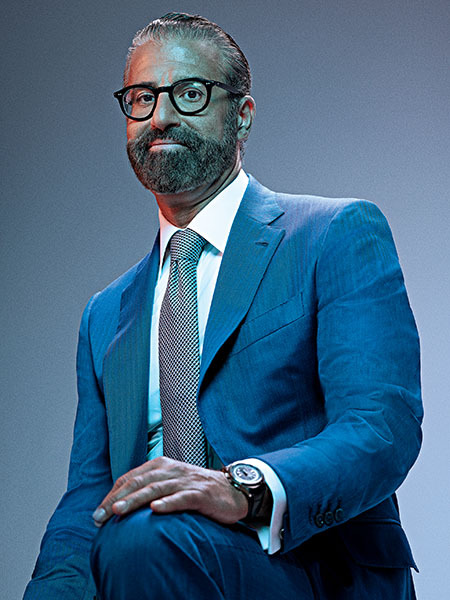

How Veritas Capital's Ramzi Musallam turned tragedy into the American dream

After the shock suicide of founder Robert McKeon, (now) billionaire Musallam convinced investors to take a bet on him, then the second-highest ranking executive in Veritas. Today, its assets have grown from a humble $2 billion to a whopping $36 billion

Ramzi Musallam returned to his desk after a quick trip to the bathroom on September 10, 2012, to find his assistant visibly shaken. She informed him that a call had come in about Musallam’s boss, Robert McKeon. He had just killed himself in his southern Connecticut mansion at the age of 58.

Musallam jumped in his car and raced the 40 miles from Midtown Manhattan to Darien, Connecticut. He was close to McKeon and knew his boss was struggling with his mental health. But Musallam never expected McKeon would take his own life. He was a force of nature. Through sheer will, McKeon had worked himself up from the streets of the Bronx, where his father was a Drake’s Cakes delivery man supporting seven children, to the upper echelons of finance. Musallam was in shock.

“It was just so devastating,” Musallam says. “For as long as I had known him, we had worked together. It was tough. I had never experienced anything like this.”

While McKeon’s American dream had soured into a nightmare, Musallam’s was about to soar. He returned to the office to devise a plan to stave off the collapse of Veritas Capital, the private equity firm McKeon had founded in 1992.

Musallam had come onboard in 1998 and was Veritas’ second-highest-ranking executive. The morning after the suicide, Musallam began holding emergency meetings with the company’s investors. McKeon’s death meant they suddenly had the right to tear up their commitments to fund Veritas’ deals. Instead, Musallam persuaded them to bet on him. He also cut a deal with McKeon’s family that would transfer ownership of McKeon’s majority stake in Veritas, mostly to Musallam. Years later, the hasty deal would produce bad blood—and a lawsuit—between Musallam and McKeon’s family.

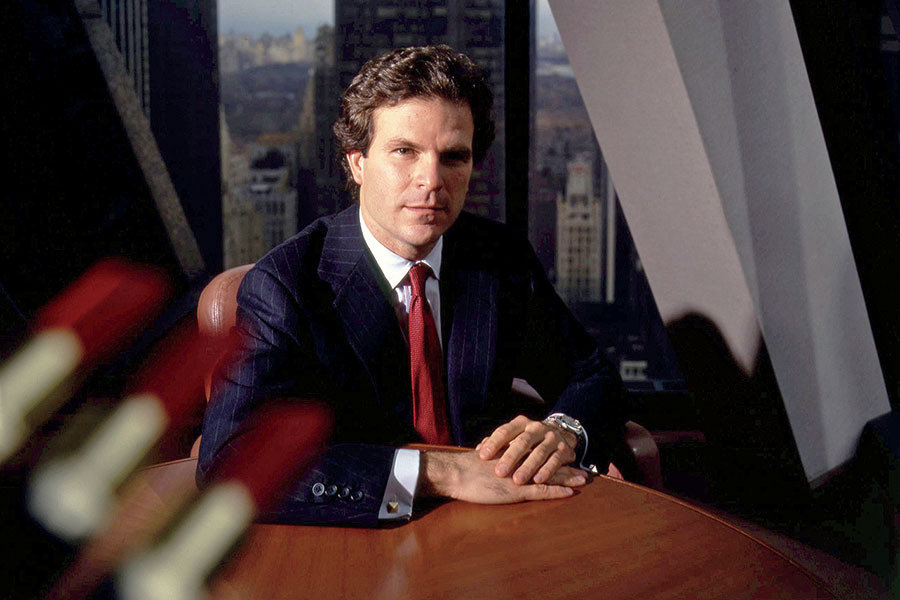

High Flier: At 38, Robert McKeon was a Wall Street wunderkind doing big deals at Wasserstein Perella, such as a reported $300 million buyout of makeup company Maybelline in 1990. He even contemplated running for governor of Connecticut. It would all come crashing down 20 years later when he took his own life at 58

High Flier: At 38, Robert McKeon was a Wall Street wunderkind doing big deals at Wasserstein Perella, such as a reported $300 million buyout of makeup company Maybelline in 1990. He even contemplated running for governor of Connecticut. It would all come crashing down 20 years later when he took his own life at 58But these manoeuvres laid the foundation for a stunning Wall Street success. Nearly a decade later, Veritas Capital’s assets have grown from $2 billion in 2012 to $36 billion today, and its funds have generated staggering net internal rates of return of 31 percent. The funds have lost money on only a single investment ($87 million on a solar panel company in New Mexico), and since Musallam took over, Veritas has distributed $12 billion to its investors. At 53, Musallam finds himself worth an estimated $4 billion, good enough for a debut appearance on this year’s Forbes 400.

Musallam produced this track record by focusing on technology companies that operate in sectors dominated by the United States’ federal government, particularly defense, health care and education. America’s $6.8 trillion worth of annual spending and sweeping regulatory power give it unparalleled sway in these markets. While many buyout firms try to avoid investing in areas affected by government interference, Musallam’s strategy hinges on understanding what the most influential player in the global economy will do next.

“I and the firm maintain a very close proximity to government because government is at the forefront of all the complexities and issues that confront us,” says Musallam, sitting in his Manhattan office, whose broad views of Central Park mark it as distinctly distant from Washington, DC. “These are government-influenced markets, no doubt about it, and being close to how the government thinks about those markets enables us to understand how we can best invest.”

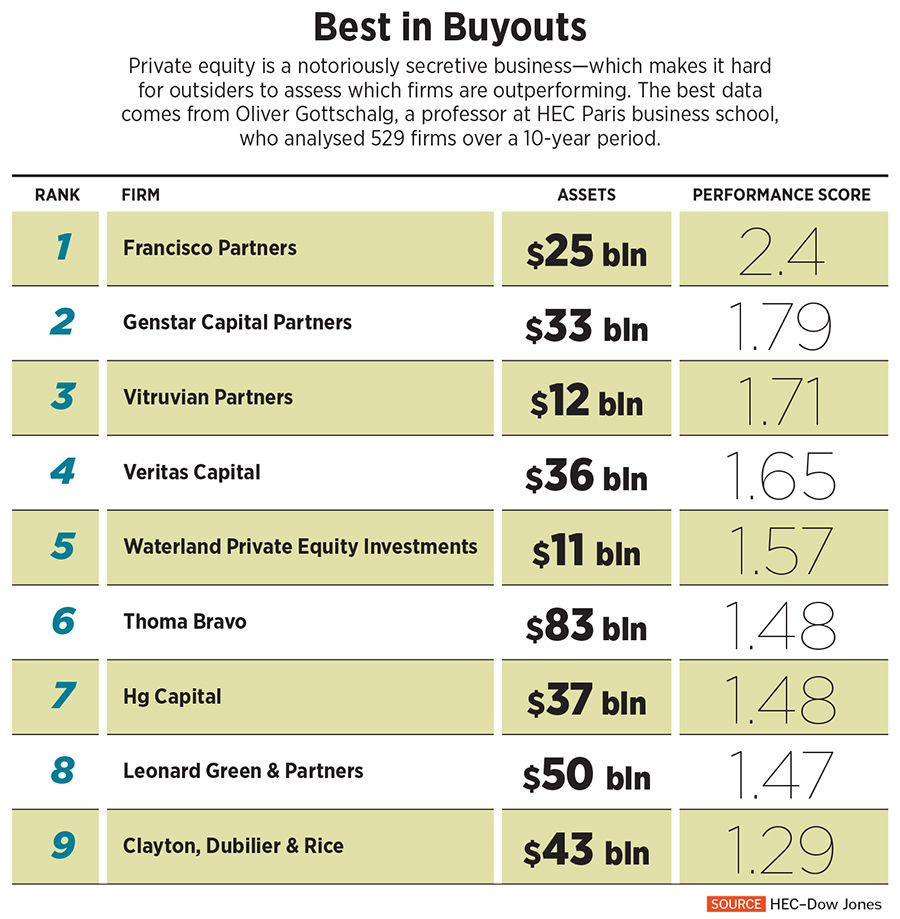

The formula has worked. In January, Veritas was listed as the private equity industry’s fourth-best-performing firm by the closely followed HEC–Dow Jones ranking (see ‘Best in Buyouts’), ahead of high-flying firms like Thoma Bravo, Vista Equity Partners and Clayton, Dubilier & Rice.

Despite his ease navigating Washington and Wall Street, Musallam shuns publicity. He rarely speaks to the press. He is one of a handful of financiers with top government security clearance.

“There are people in the private equity world who have a lot of visibility. That is not Ramzi. He is understated but extremely effective,” says David Solomon, CEO of Goldman Sachs. “He has quietly built an extremely valuable business being at the intersection of government-regulated markets and technology, which is rare for private equity.”

A Palestinian Christian born in Jerusalem, Ramzi’s father, Samih Musallam, landed in New York City in late 1950, shortly after the first Arab-Israeli war in 1948. His first night at the YMCA, all his belongings were stolen. He persevered, eventually earning a civil engineering degree from the University of Missouri before settling—and prospering—in Effingham, Illinois. By the mid-1960s, the now successful Samih returned to the Middle East; his second son, Ramzi, was born in 1968 in Amman, Jordan.

Samih Musallam worked for the US Army Corps of Engineers, moving his family constantly. Ramzi’s formative years were spent in emerging markets such as Saudi Arabia and Tanzania. “We were literally in the middle of nowhere—there was nothing there, no village, nothing,” recalls Musallam of his years in Africa. “We were homeschooled and learned through correspondence. There was no iPad. We would do an assignment and my mom would mail it in.”

Musallam says the experience was an immersion course in navigating relationships with people from different cultural backgrounds, one that taught him sensitivity and resilience. His family was once held at gunpoint in Tanzania and shaken down by bandits on a dirt road. “I thought it was normal,” he says.

By the time Musallam was in high school, his family returned to the US and landed in Pine Brook, New Jersey. He studied economics at Colgate University and started on Wall Street as a JPMorgan investment banker in 1990 before jumping two years later into private equity at a boutique firm, Berkshire Partners. He then headed to the University of Chicago for business school, where he talked himself into a job with the investment operation of Jay Pritzker, the billionaire who built the Hyatt Hotels chain. When he graduated in 1998, Musallam headed to New York, where he was hired by Robert McKeon.

Six years earlier, McKeon had founded Veritas Capital after leaving Wasserstein Perella & Co, the pioneering investment bank co-founded by Bruce Wasserstein and immortalised in a 1989 Forbes story, ‘Bid ’em Up Bruce’, which described how the firm’s clients were often coaxed into overpaying for targets. McKeon had run Wasserstein Perella’s successful private equity arm and had grown tired of funneling most of his unit’s profits to Bruce Wasserstein.

At Veritas, McKeon owned a majority of the company and raised money on a deal- by-deal basis from a network of CEOs, including Chevron’s George Keller and Ford’s Harold “Red” Poling. His only partner was Thomas Campbell, a fellow banker who had left Wasserstein Perella with him to start Veritas and who McKeon would shove out the door in 2007.

Musallam pushed McKeon in two new directions. First, he helped convince McKeon to move beyond his deal-by-deal approach and raise private equity funds from institutional investors that would lock up cash for years. That gave them flexibility and helped the business grow. Second, Musallam figured out that defense contractors would be fertile buyout targets for funds willing to deal with theidiosyncrasies of government contracting. Starting with the purchase of PEI Electronics, a Huntsville, Alabama-based military equipment maker, Veritas cobbled together what would become Integrated Defense Technologies, which it listed on

the New York Stock Exchange in 2002. Defense deals would become Veritas’ bread and butter. When one looked particularly promising, McKeon would take a cue from Bruce Wasserstein and grab more of the riches for himself. He personally made $350 million just from DynCorp, a military contractor that was sold in 2010.

McKeon’s death tripped Veritas’s “key-person” provision, giving the firm’s investors the right to stop providing capital for new deals. Had enough of those investors walked away, it would have destroyed the firm. Musallam had six months to get through the key-person process before the investor spigot turned off. “I don’t get stressed,” Musallam says.

“I was very focussed because I knew in my heart that we had a tremendous opportunity.”

He traveled across America to meet with Veritas’ investors, ultimately convincing every one of them to stick with him and his team, partly by cutting Veritas’ management fees. “There was no real precedent for this,” Musallam says. “We got 100 percent approval from our investor base, which nobody thought we could get.”

At the same time, Musallam had to persuade McKeon’s estate, controlled by one of his brothers and established for the benefit of his four children, to transfer McKeon’s Veritas ownership to him. Absent Musallam’s efforts to get investor buy-ins, the whole firm would have collapsed, so his negotiating position with the family was strong.

By January 2013, McKeon’s family agreed to transfer ownership of Veritas in exchange for 10 percent of the proceeds of any future sale of its management company and the three general partnerships associated with its existing funds. They also retained a reduced portion of McKeon’s performance fees from existing Veritas funds and 5 percent of the performance fees for the next two funds Veritas raised. It was a complete victory for Musallam: The firm would remain in business with him as its majority owner and CEO.

“He was not just dealing with the investors and the firm—he was dealing with losing someone he was close to, and he never wavered, even answering questions that were sometimes probing and personal,” says Veritas investor Claudia Baron, who runs $6 billion of private equity investments for Chicago-based asset manager PPM America. “I thought, if that is how he acts during a stressful time, he’s going to have the same level of thoughtfulness and integrity in deal work.”

For years, Musallam was obsessed with the digitisation of health records. He was first turned on to the idea of a government–private sector partnership involving health care IT through conversations with Kerry Weems, who headed Medicare in George W Bush’s administration. Musallam made a habit of staying close to people like Weems, who controlled one of the largest budgets in the US government. Veritas would dip its toe into these waters in 2007 by buying its first health care IT services firm, Vangent. It would sell the company to General Dynamics four years later for a $350 million profit.

“Health care is a broken system,” Musallam says. “My fundamental belief is that technology can improve it.”

In 2012, Musallam approached information giant Thomson Reuters about buying the businesses it had cobbled together to provide data on insurance claims and health care expenditures to hospitals and insurance companies. Musallam was certain that Veritas needed to go big on health care data—and after putting up $465 million, Veritas was able to acquire the group in a $1.3 billion leveraged buyout, making it one of the firm’s largest bets.

Musallam renamed the Thomson Reuters unit Truven Health Analytics and initiated $165 million of new capital expenditures to help transform the company from a mere data provider into a business that could help customers learn how to provide better care while reducing costs and waste. To speed things along, Truven was paired with a defense intelligence software company Veritas had purchased from Lockheed Martin that had already developed efficient algorithms to analyse petabytes of data.

“We make our companies collaborate,” Musallam says. “It’s not a nice thing to do, it’s a requirement.”

Musallam pivoted Truven toward the public sector. It began selling its services to government customers such as Medicare for the first time. In 2016 Truven sold to IBM for $2.6 billion, making Veritas 3.2 times its original investment.

Veritas is the rare government-focussed buyout shop that does not hire prominent former politicians or government officials. Instead, Musallam prefers to tap into decades of relationships. He spends a lot of time sitting through briefings in “sensitive compartmented information facilities” (SCIFs) set up by the military, for which top security clearances are required—and mobile phones are banned.

“The US government is the largest single investor in technology, bar none, by multiples of what the entire venture capital community invests—dozens of different federal agencies investing directly into companies,” Musallam says. “A lot of the businesses that we’re very familiar with have gotten their start through government-funded customer R&D programmes. Google, Apple, a lot of what is on your iPhone. Tesla is another example, the space companies—built through collaboration in some form with the government.”

The burgeoning field of cybersecurity is another focus for Veritas. In 2014, Musallam bought a busted security startup called BeyondTrust, putting up $145 million of equity in a $310 million buyout. Veritas had BeyondTrust boost its R&D spending by 44 percent to bolster its products, which stop both rogue employees and external bad guys from hacking in. BeyondTrust’s revenue swelled, growing 20 percent a year, and in 2018 Veritas sold it for $755 million, making 3.8 times what it put in.

Musallam has kept one foot firmly in the defense arena. In 2015 Veritas, together with some co-investors, put down $845 million to buy flailing aerospace repair company StandardAero from Dubai Aerospace in a $2.1 billion deal. Musallam had just raised $1.9 billion for Veritas’ first new fund under his watch and wagered a big chunk of it on the Scottsdale, Arizona, company. (Musallam knew aerospace well given that Veritas had formerly owned Vertex Aerospace, a StandardAero competitor.)

StandardAero quickly expanded in Europe and Asia. Having developed a way to trim the time required to repair jet engines, it was soon winning new government contracts. In 2019, Musallam sold StandardAero to Carlyle Group for $5.3 billion, more than tripling Veritas’ initial investment.

By 2019 Veritas was humming, with all five of its buyout funds performing in the industry’s top quartile, according to research firm Preqin. Simultaneously, the great bull market had outside investors lining up to own stakes in Wall Street’s most successful firms, and in 2020, New York–based Dyal Capital approached Musallam to buy a stake in the business. In October 2020, Musallam agreed to sell 11.8 percent of Veritas to Dyal for $725 million in cash, plus a $200 million sweetener in the form of a loan to Veritas, which created a windfall for Musallam and his Veritas partners, who pocketed most of the proceeds. The deal valued Veritas at $6.2 billion, with Musallam retaining a majority stake.

Unfortunately, the Dyal deal upset Robert McKeon’s heirs. This February, the family sued Musallam for breach of contract, claiming the $200 million loan was designed to cheat them out of their right to 10 percent of the proceeds of any sale of the firm, some $20 million. In court, Musallam claimed he stayed true to the contract. “A loan is not a sale,” he stated. In September, the New York State Supreme Court agreed with Musallam and tossed out the case.

While dealing with McKeon’s family, Musallam worked from a desk near a large picture of his father, Samih, who died a decade ago. It’s a reminder that the American dream is alive and well—but also that great happiness requires more than just great wealth.

“He did what you hear and read about—he took the boat to New York,” Musallam says. “He’s overlooking and watching me.”

(This story appears in the 19 November, 2021 issue of Forbes India. To visit our Archives, click here.)

Post Your Comment