How Prasad Chalavadi's 'saree with software' business has gone the extra yard

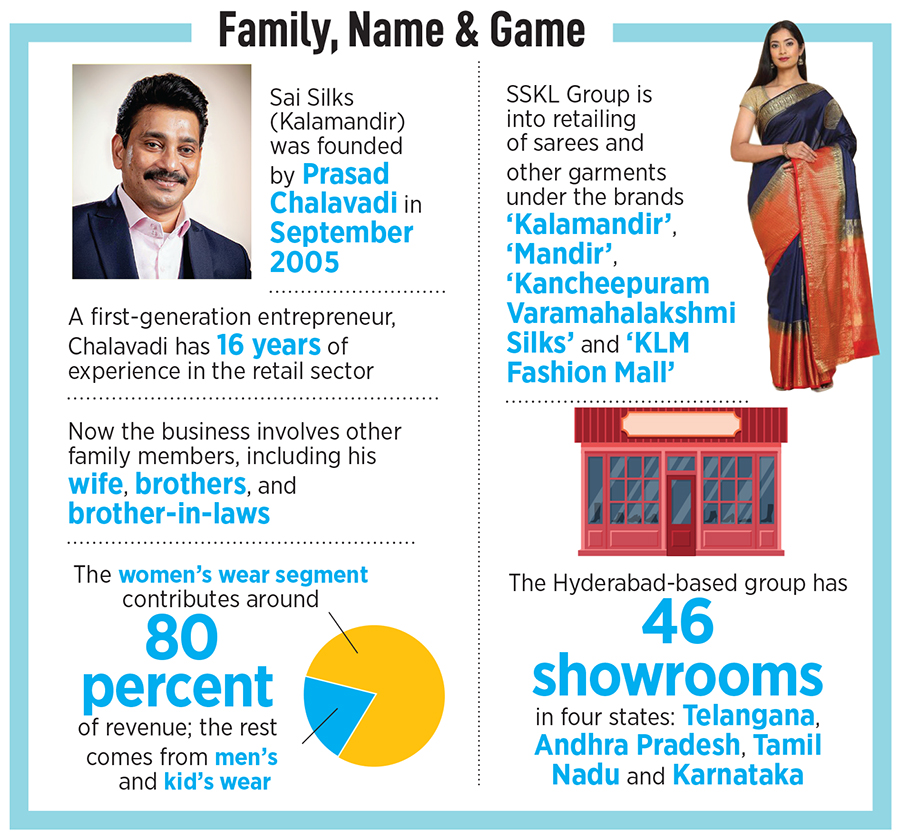

Chalavadi has built Sai Silks (Kalamandir) into a formidable brand across South India, with 46 showrooms in four states: Telangana, Andhra Pradesh, Tamil Nadu and Karnataka. Now his love for the six yards is taking him to the IPO market

Team Sai Silks (Kalamandir), from left: Durgarao Chalavadi, whole-time director, head operations (Karnataka); Kalyan Srinivasa Annam, whole-time director & head of advertisement projects; Venkata Rajesh Annam, senior VP-operations (Andhra Pradesh); RB Bharadwaj, senior VP-IT & ecommerce; Mohan Chalavadi, senior VP-operations (Telangana); Jhansi Rani (seated), head-retail; Annam Subash, head of sourcing; Prasad Chalavadi, founder & managing director Image: Vikas Chandra Pureti for Forbes India

Team Sai Silks (Kalamandir), from left: Durgarao Chalavadi, whole-time director, head operations (Karnataka); Kalyan Srinivasa Annam, whole-time director & head of advertisement projects; Venkata Rajesh Annam, senior VP-operations (Andhra Pradesh); RB Bharadwaj, senior VP-IT & ecommerce; Mohan Chalavadi, senior VP-operations (Telangana); Jhansi Rani (seated), head-retail; Annam Subash, head of sourcing; Prasad Chalavadi, founder & managing director Image: Vikas Chandra Pureti for Forbes India

October 2005, Hyderabad. Prasad Chalavadi starts the show with a request. “If you want to see the magic, then please follow the instructions,” says the man from Vijayawada. An excited bunch of around dozen young women and men—including a few employees in a 3,213 square feet outlet where the show was being organised—stayed glued to the gestures of the 37-year-old, and nodded their head in approval. Chalavadi came from a family business of spices, went to Dubai and the US after finishing his college and MBA, armed himself with software programming courses, and worked with an IT firm for a few years. He then came back to India in 2003 and hosted his maiden show two years later.

After a few more steps, Chalavadi pauses and scans the reactions of the onlookers. He then gets into the penultimate act with a few more dos and don’ts. First, ensure that the saree doesn’t entangle with the petticoat. Second, use pins to tie, but don’t use too many as the fabric gets spoilt. Lastly, walk a few steps to get a feel of the saree. “Be confident. Magic happens when confidence seamlessly merges with the saree,” he says. The crowd applauds and disperses, a few consumers walk in to buy sarees from the ‘Kalamandir’ store, and Chalavadi, who founded Sai Silks (Kalamandir) in 2005, calls his store manager after finishing his demonstration. “It’s only when you go through the extra yard, you get six yards of love, beauty and grace,” he says.

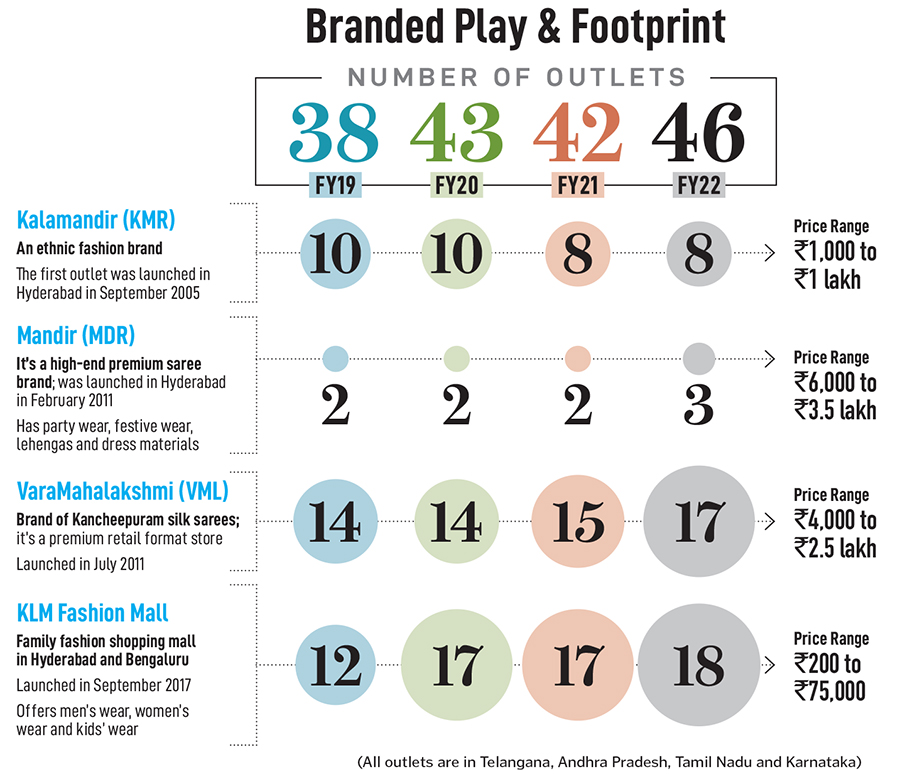

Fast forward to July 2022. Chalavadi is getting ready to see how far his love for the six yards can take him. Sai Silks (Kalamandir), which closed FY22 with an operating revenue and profit after tax of ₹1,129.32 crore and ₹57.67 crore respectively, has filed the draft red herring prospectus (DHRP) for an initial public offering (IPO) of around ₹1,200 crore. The move makes Sai Silks (Kalamandir) the first saree retailer in India to go public. The company, which operates under four brands—Kalamandir, Mandir, VaraMahalakshmi and KLM Fashion Mall—gets over 65 percent of the revenue from sarees. It has 46 outlets across Telangana, Andhra Pradesh, Tamil Nadu and Karnataka, and has played its cards well to cater to every segment of the society.

Chalavadi explains the various branded pillars—he calls them pleats—of his company. Kalamandir, which started in 2005 and now has eight outlets, targets the middle and upper middle class by selling sarees within a price band of ₹1,000 to ₹1 lakh; Mandir, which was rolled out in 2011 and has three outlets, caters to the super-rich. The price range for sarees starts from ₹6,000 and goes up to as much as ₹3.5 lakh.

Then there is the ethnic silk sarees brand VaraMahalakshmi, which is meant for festivals, weddings and occasional wear, and has a price range of ₹4,000 to ₹2.5 lakh. And the fourth and the youngest ‘pleat’ is KLM. Started in 2017, it’s a value-fashion brand for the family. “It is for the masses,” says Chalavadi, founder and managing director of Sai Silks (Kalamandir).

Then there is the ethnic silk sarees brand VaraMahalakshmi, which is meant for festivals, weddings and occasional wear, and has a price range of ₹4,000 to ₹2.5 lakh. And the fourth and the youngest ‘pleat’ is KLM. Started in 2017, it’s a value-fashion brand for the family. “It is for the masses,” says Chalavadi, founder and managing director of Sai Silks (Kalamandir).But why an IPO? Chalavadi laughs. Back in 2005, he recalls, most of his friends, well-wishers and even the ones who didn’t know him asked an almost similar question: Why sarees? Some found the move baffling. “How can a software guy sell sarees?” they wondered. Others took a dig. “The guy has gone crazy,” they said. And a few turned prophetic. “Wait for some time. This guy will shut down,” they predicted.

Chalavadi was neither surprised nor shocked. “It’s human nature. All like to bet on winning horses,” he says. Back in 2005, he was seen as a new kid on the block. “He has entered the race but will never be able to run,” opined a saree retailer who had been working with a legacy brand for decades.

Chalavadi remained unfazed. His belief in science, data and numbers helped him stay focussed. “I was emotional when I opened the first two stores,” he recalls. But after that, emotion took a backseat. The business, he underlines, is all about managing inventory and cash flow. “If you master these two, then you are sorted,” he says. The first-generation entrepreneur started rewiring the orthodox saree business.

For ages, the saree industry was largely unorganised, relying heavily on an intricate network of relationships among weavers, employees and retailers, and dominated by a few regional saree brands with their pockets of influence.

Chalavadi, after analysing the loopholes and weaknesses, turned geeky. “We started tracking movement of every product from production to the sales counter,” he says. Machine learning and artificial intelligence were used to anticipate and predict demand of thousands of stock-keeping units (SKUs), and take stock of the ageing of the products. “I put proper systems and software in place,” he says.

His ‘saree with software’ strategy seems to be paying off. In its recent note, ratings agency CARE outlines what has worked for the retailer from Hyderabad. The business operations of the company, the note underlines, have benefited from the promoters’ long-established track record and the vast industry network developed over the years. Further, it is financially backed by its promoters who regularly infuse funds to support the company’s growing scale of operations, the note underlines.

With other family members such as Chalavadi’s wife, brothers and in-laws now part of the business, the organisation has a defined structure and role for all.

The entrepreneur is now betting big on a promising future. What gives Chalavadi hope is the resilient nature of the business. As long as the institution of marriage exists, sarees will remain in business, he says. Depending on their social and economic standing, people will uptrade and downtrade, but will keep buying sarees. “It’s an evergreen business,” he says. Even in the wake of cyclical economic patterns—take, for instance, the 2008 global financial meltdown—or a black swan event like the Covid-19 pandemic, the demand will rebound.

The numbers seem to back the claims made by the saree retailer. From a high of ₹1,175.46 crore in FY20, the operating revenues did tumble to ₹677.14 crore in FY21, but there was a sharp uptick during the next fiscal. “I strongly believe there is a very bright future for the saree business,” says Chalavadi, adding that the company has been diversifying over the last few years. “We are no longer a saree-only company,” he says.

Chalvadi’s wife, Jhansi Rani, who looks after retail, marketing, sales, administration and human resources at the business, chips in with her take. “Saree is an emotion. I don’t see it as a product,” she says. Jhansi Rani has also been an integral part of the team assigned with sourcing of products, and maintaining relationships with vendors from different parts of the country. “His [Chalavadi’s] passion for the business is unmatched,” she says.

For brand experts, the success of Sai Silks (Kalamandir) has to do with the innovative selling model devised by Chalavadi. Retail industry of any kind is used to two kinds of format, says Harish Bijoor, who runs an eponymous brand consulting firm. First is the kirana style of retailing, where the retailer or the salesman is sitting behind the counter. Second is the modern retail format which is a do-it-yourself model. “Prasad rolled out assisted selling,” he says. The in-store consumer experience, having a vast range of sarees at an unbeaten price is what helped him carve an edge over rivals and grow quickly in 17 years.

The challenges, however, remain. One of the big ones is pointed out by CARE. The retail business has low-entry barriers and is highly competitive due to the presence of innumerable unorganised players. The industry is extremely varied, with a hand-spun and hand-woven sector at one end of the spectrum, and the capital-intensive sophisticated mill sector at the other. The ecommerce industry is also expanding at a rapid pace in the country and poses a threat to the brick-and-mortar retail business, says the note by CARE.

The second challenge might come from legacy players. In its key markets of Telangana, Andhra Pradesh and Karnataka, the company faces intense competition from RS Brothers group, Chandana group, JC Brothers group, Kalanikethan Silks and Nalli, the note adds. Geographical concentration of revenues and presence could pose a challenge.

Kalamandir's first outlet was launched in Hyderabad in September 2005

Kalamandir's first outlet was launched in Hyderabad in September 2005Bijoor points out another potential issue. “Another Sai Silk can emerge in three years or so,” he says. The company, therefore, not only needs to continuously stay ahead of the curve and innovate with fashion, but it must also feel the consumer pulse. “It has to consistently play a sharp differentiated game,” he says.

Chalavadi, for his part, says that he is well-prepared. “I have built a viable business model and will ensure it always remains so,” he says, adding that the biggest plus for the company has been its financial discipline. Does he fear failure? Chalavadi smiles. “If you are worried about failure, then you will never succeed,” he says, adding that every individual will have to go through the phase of failure. “But what matters is how you come back and what you learn,” he says.

(This story appears in the 12 August, 2022 issue of Forbes India. To visit our Archives, click here.)