Tata Motors 2.0

How Guenter Butschek's transformational strategy is working almost three years after he slipped into the hot seat at India's largest automaker

“ When I joined three years ago… it was clear that we needed to change the strategic direction.

Guenter Butschek, CEO & MD, Tata Motors Worldwide

In February 2016, barely a month after he took over at Tata Motors, India’s largest automaker, Guenter Butschek was poised to show the world, and his company, that he meant business.

Tata Motors’s new launch, the Zica, a hatchback that the company had showcased at the Auto Expo in New Delhi that month, was ready to be rolled out. But it had the same moniker as the global mosquito-borne virus that was killing infants or causing congenital abnormalities.

As Tata Motors went looking for an alternative name, it gave Butschek some extra time and breathing space. But, instead of sitting idle, the German used the time to appraise the product and slip in improvements. “We anyway had the time because of the renaming, [so I thought] it was a good time to bring quality improvement as well as spread the message across the organisation that quality control will be stringently applied to all future products,” he told Forbes India in Jodhpur in early December 2018, where he and his team were showcasing the company’s latest offering, the Harrier, a compact SUV.

Today, Tiago, the rechristened Zica, is one of the largest selling vehicles for Tata Motors, with sales of nearly 8,000 units a month. But, more importantly, Butschek’s focus on quality, even in the last mile, conveyed to the 59,000 employees of the Mumbai-headquartered company why the Tata Group had turned to him to lead Tata Motors. Butschek has a reputation for restructuring companies to improve productivity and profitability; this was shown between 2002 and 2005 when he was president and CEO of Netherlands Car BV, a joint-venture between Daimler and Mitsubishi Motors Corporation. (In 2012 Dutch coach maker VDC acquired the company and renamed it VDL Nedcar.) And he was here to do that to Tata Motors as well.

Between 2006 and 2016, Tata Motors’s domestic passenger vehicle business was struggling. Of course, there had been glorious moments, such as the acquisition of Britain’s Jaguar Land Rover (JLR) for $2.3 billion in 2008, and the launch of Nano, the world’s cheapest car, in 2009. But there were plenty more to offset the positives: The company faced the wrath of farmers in West Bengal’s Singur over the Nano manufacturing plant in 2006, in addition to the company’s steady decline in market share, and the failure of the Nano. Then, in 2014, CEO Karl Slym committed suicide after which the company didn’t have a CEO for over two years.

“When I joined three years ago, our product portfolio was possibly not the most attractive one. We were not known to lead launches. Some even concluded that we had an outdated portfolio, while others were consistently bringing in modern products,” says Butschek. “We were under huge pressure because of lots of new launches by rivals. At the same time, we saw huge pressure on the contribution margin. Even Ebitda was negative. It was clear we needed to change the strategic direction. You needed to take a call on whether the business is sustainable and viable.”

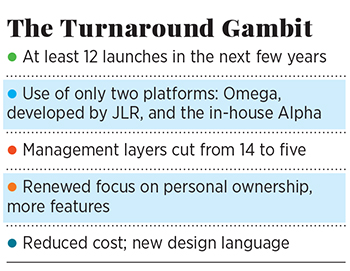

For Butschek, that translated into what he calls Turnaround 1.0 during FY18, aimed primarily at the commercial vehicle segment, with some trickle-down effect on passenger vehicles. It pertained mostly to structural changes in the organisation. In 2018, he kicked off Turnaround 2.0, under which the company is attempting a recovery in its fortunes through newer models, cost reductions, wider integration with JLR, and making the business more self-funded and profitable.

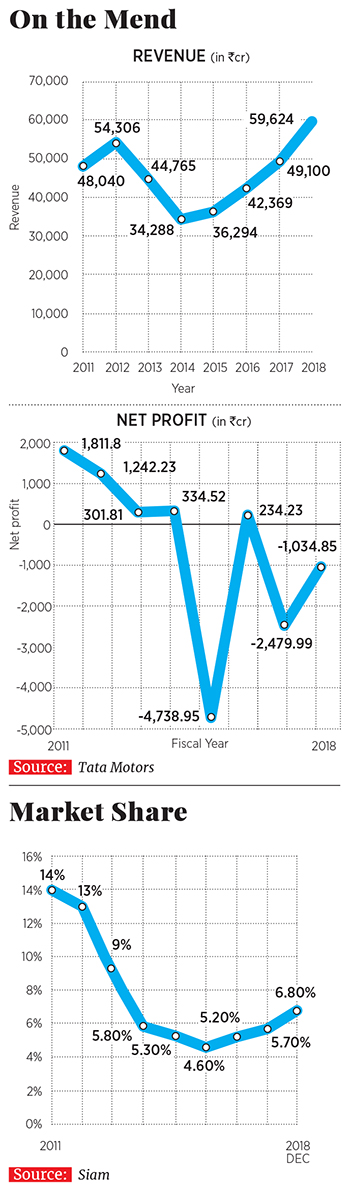

The results have already begun to show. Today, even as JLR accounts for about 78 percent of Tata Motors’s revenue, the company has increased its share in the domestic passenger vehicles market from 4.6 percent in 2016 to 6.8 percent in December 2018. A decade ago, Tata Motors held more than 13 percent, largely helped by iconic models such as the Indica and the Sumo.

“This is what you can expect from Tata Motors in future,” Butschek says. “Products that are leading in design and performance, and which will take you through your life cycle as a customer of Tata Motors.”

What was wrong?

What necessitated a course correction for Tata Motors? A rollercoaster ride for its domestic business for a little more than a decade.

In 2008, as the global financial crisis gained steam and JLR was looking for suitors, Tata Motors swooped in with $2.3 billion, joining the global big league. The purchase was followed by the much-anticipated launch of Nano in 2009, a vehicle that the company’s erstwhile Chairman Ratan Tata called “people’s car”. Back then, the company had a domestic market share of around 14 percent; while it was less than the 17 percent of 2006, models like Indica, Manza and Safari helped keep the wheels rolling.

From there, it went downhill. “There were many factors,” says Butschek. “We had issues about complacency, quality, cost, and missing products. For example, we did not even address 50 percent of the market because we had no product. We invited the competition to take our space, and it had nothing to do with changes in the regulatory environment. It was just our inability to take quick actions and to translate changes into a proper product.”

The period also saw turbulence within the senior management: Between 2008 and 2016, there was the unexpected resignation of one CEO, Carl-Peter Forster, and the death of another (Slym).

Deepesh Rathore, director at consulting firm Emerging Markets Automotive Advisors, explains the faulty product portfolio. “They had one platform [Indica], on which they developed three other models [Indigo, Marina and Indigo CS], with half-decent engines. Their quality levels were bad, and they had moved into the taxi market, making them irrelevant to personal buyers. In the taxi space too, they were beaten by Maruti, Hyundai and even Honda, as Uber and Ola came in.”

There were also serious concerns about the quality of the cars, says Arun Malhotra, former managing director at Nissan, and a veteran at Mahindra & Mahindra, and Maruti Suzuki. “If not for JLR and the commercial vehicles doing well, any other automobile company would not have been able to survive,” he says. “Many dealers left them during those times.”

The competition too was heating up, as Mahindra became one of the top three manufacturers, with a series of launches like XUV500 in October 2011. “The competitors gave a much better product, with improved features,” says Puneet Gupta, associate director of Automotive Forecasting at IHS Markit. “The Tatas had not kept up and reinvented themselves.”

The Harbinger of change

In 2016, after looking for a CEO for two years, Tata Motors finally appointed Butschek, who was previously the COO at Airbus, where he focussed on industrial strategy, global operating systems, supply chain, and launches. The 57-year-old’s task was to improve Tata Motors, particularly since JLR had a separate managing director who reported directly to the board.

Butschek began by bringing in radical changes, which included “six relevant angles of attack”. ‘Angles of attack’ is a phrase used in the aeronautical industry and refers to the angle between an aircraft wing and the direction of the wind, which helps in lifting the aircraft. For Tata Motors, the six angles meant top-line cost reduction, improvement of core processes, customer centricity, new technologies, business models and partnerships, and a lean and accountable organisation.

First, the company decided to shift its entire product offering on to two platforms (a design architecture that includes the underfloor, engine compartment and the frame of a vehicle): Omega, developed by JLR and used in its wildly popular models Discovery; and Alpha, which was developed in-house. The company intends to develop over 12 products in the next few years on these platforms, reducing development and manufacturing costs, unlike earlier when there were multiple platforms for various models. Among its coming launches, Harrier will be based on the Omega platform, and a new hatchback, expected by mid-2019, on Alpha.

“You can go for the design solution of a new architecture and then you can stretch it to a certain extent,” Butschek says. “You reach the limits and you need to ask yourself, would I like to be in a segment above it? We had been working on the Alpha architecture, which roughly covers vehicles from 3.7 to 4.3 metres. But we said we also need to be in the segment above 4.3 m, not because this is where the volumes are but because this is where we start building the brand and offer customers an opportunity to grow with us.”

Then, there were the complicated layers of management that Tata Motors was infamous for. There were, Butschek says, 14 layers that affected overall productivity. The company brought that down to five, to ensure a lean structure and faster communication. “In some ways, it is good to have a foreigner come in and do this,” says a former managing director at a rival car company. “Unlike Indians, they can get rid of people, and ensure a leaner organisation.”

Perhaps, it were these attempts at bringing in a change that led to speculation of his own exit. Rumours about Butschek’s future in the company started doing the rounds after the man who appointed him, Cyrus Mistry, was booted out of Tata Sons in October 2016. But Butschek put all doubts to rest in August 2017 when he called the rumours “extremely annoying”. “The fact that I was recruited by the previous Tata Sons leadership has nothing to do with my loyalty to Tata Sons and Tata Motors,” he had said. “I came to India purely on a professional agenda.”

The Turnaround

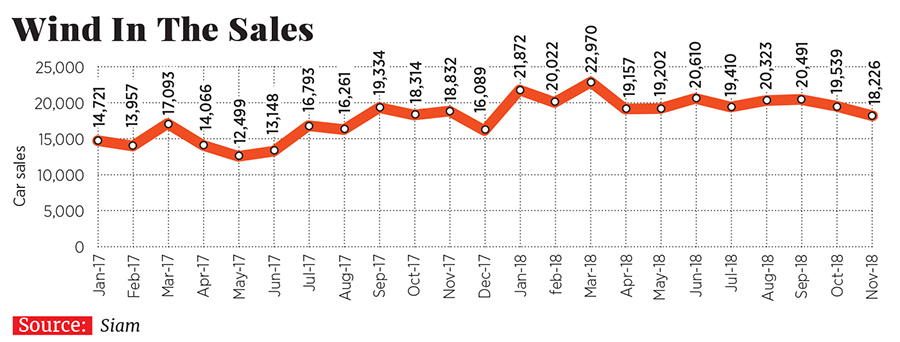

Since the turnaround strategy was put in place in 2017, the company has seen sales figures go remarkably north. Between April 2017 and March 2018, Tata Motors sold a total of 184,743 passenger vehicles, a growth of 19 percent over 155,260 units sold year-on-year. Between April and November 2018, cumulative passenger vehicle sales growth in India stood at 142,137 units, a growth of 24 percent over the same period in the last fiscal.

“If you look at Tata Motors over the past few years, Tiago and Tigor have been able to win back the numbers that Indica lost earlier,” says Rathore of EMAA. “But the big difference has been Nexon, and between April and November 2018, it sold 26,000 units more than it did in the same period in 2017. That’s a significant leap.”

Then, in a shift away from the taxi segment, Tata Motors began to cater to individual consumers. Mayank Pareek, president of Tata Motors Passenger Vehicles and a 20-year veteran of Maruti Suzuki, has been instrumental in making this possible.

Says Rathore, “They have successfully moved away from the taxi space to the personal ownership space. For a while the company was irrelevant, and now they are seeing a comeback. In the long term, personal ownership is important for the company, and what has really worked for them is the coming of Pareek and new-generation products.”

“I believe a car is not sold in the showroom,” Pareek says. “It is sold at the dining table. Everybody who is buying a car considers 2.6 cars on an average, and one of those 2.6 cars should be ours. After that, we will ensure that things are fine.”

Experts agree that the focus on personal ownership is helping the company regain lost ground. It has also helped that Nexon, Tata’s compact SUV, recently got a five-star rating from Global NCAP at the latest round of crash tests; it became the first made-in-India, sold-in-India model to register this high a score.

Over the past few years, Pareek has also gone around creating 24 vehicle modular units that comprise components such as engines and infotainments. “We divided the car into 24 modules, and decided we needed to reduce the cost by half across each,” he says. Pareek would then travel to Pune, where the company has its design and manufacturing facilities, every week to monitor the situation and cost reductions. “The amount of cost-saving we are doing now is more than five times higher than what the company has ever done.”

Says Malhotra, “The company is on a turnaround path and has been doing well in the hatchback segment. But pricing could be a cause for worry. Companies like Maruti Suzuki have been making profits on every car. But, as far as Tata goes, they have been in the penetrative pricing zone, which needs to change.”

Meanwhile, the commercial vehicle business, where the company was losing market share, has also seen a rebound. Between April and October 2018, the company expanded its market share in medium and heavy commercial vehicles, which include trucks and buses, to a three-year high of 51 percent, according to Siam. In FY17, the share was 49.2 percent. This comes at a time when commercial vehicle sales have seen a slowdown.

Much of the improvement in the company’s new offerings, such as the Harrier, is also partly thanks to Tata’s close working relationship with JLR. “This combination is something we need, and it was clear that such a route would be faster than going for iterations or developing our own architecture,” says Butschek. “The future of Tata Motors is going to be two architectures that are versatile.”

Then, there is the company’s new design language, evident from the Harrier and the Nexon. The company has three design studios—in Pune, Turin (Italy), and Coventry (the UK). Pratap Bose, the head of design at Tata Motors, says, “Customers are looking at newer options. And we are keen on following through. There’s no point in raising the bar and expectations and then not delivering.”

That’s something the company is trying work on. In February 2018, when it announced plans to launch the Harrier, there wasn’t much expectation, given Tata Motors’s reputation of not producing products it showcased. For instance, in 2009, it showcased the Prima, a concept luxury sedan, which never went into production; the same happened with the Pixel, a small car showcased in 2011. “If I speak about product development, the focus is on three attributes: Cost, time and the quality,” says Rajendra Petkar, CTO, Tata Motors. “The coordinated approach, as a team, is now paying off. Who would have believed that we would’ve launched the Harrier so soon.”

Yet, despite all these changes, Tata Motors is still a long way from making a full recovery. For one, Maruti Suzuki accounts for half the cars sold in the country, while Hyundai India accounts for a little more than 15 percent.

“There has been an overall infusion of energy into the [Tata Motors] brand,” says Gupta. “The dealers are excited, unlike before, and they have been able to create excitement. Suppliers now want to work with Tata. But there will also be intense competition in the coming years with KIA and MG Motors, among others, coming into India.” This means Tata Motors will have to hasten its turnaround to gain a foothold in the Indian market, currently the world’s fourth largest automobile market.

While the company is still to reach a position where it will have significant sway over pricing, it has begun to show early signs of doing so. Since January 2018, it has initiated three price hikes, and is expected to raise prices from 2019, signalling its ability to begin dictating prices in a competitive economy. “If they want to take on Hyundai India and Maruti Suzuki, they will have to sell many thousand units more than what they sell at the moment,” reckons Malhotra. “They will also have to take a relook at their pricing strategy.” The Harrier, meanwhile, is expected to be priced between `14 lakh and `18 lakh, which will help it bring considerable volumes. It will be competing in the compact SUV segment with Hyundai’s Creta, Renault’s Duster and Jeep’s Compass.

So where does Tata Motors go from here? “It’s an all-around performance improvement at Tata Motors, which has been initiated by the transformation, and which has been significantly accelerated by the turnaround that is now part of the DNA. It’s no longer something top-down, but deeply rooted in the organisation.”

It may be too early, but Tata Motors seems to have gotten the engine revving, again.

(This story appears in the 18 January, 2019 issue of Forbes India. To visit our Archives, click here.)

Post Your Comment