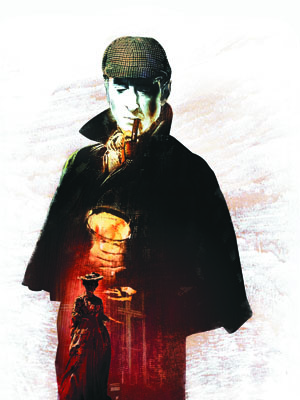

The Woman Of Sherlock Holmes

It is possible that Sherlock Holmes was not above love and sex

The first thing that most novices of the stories of the world’s greatest detective, Sherlock Holmes, ask is whether he was real or fictional. With that question settled decisively (he was very much a real person in the flesh and blood of Victorian vintage, for those who like to believe so), we shall turn our attention to the second thing that the dilettantes pose: Did he ever fall in love, marry or have sex? Alas, there is no one-word reply to this query and one must dive deep into the crevices between the lines of those 56 short stories and four novels of Sir Arthur Conan Doyle to answer it once for all.

The stories work on multiple layers. On the most superficial level is the declaration by the busy detective that he has no time or inclination for female company. In fact, he seems to nurture several of that era’s stereotypes about women. “Women are never to be entirely trusted — not the best of them,” he tells Watson in The Sign of Four. He avows not to marry because a wife would be a drain on his brain. So, you can’t be faulted for coming away from your first reading him, thinking Holmes avoided women.

But as you read him again, and again, an entire new world of romance, sex and even perversion opens up. You suddenly know why so many adults are addicted to the Holmes canon. All the sexual symbolism stashed away in seemingly innocuous mentions comes alive. You realise how the Holmes-Watson pair never fails to scan over the assets of almost every woman that walks into 221B, Baker Street. You discover that it is a nude Lady Frances Carfax, perhaps a sexual slave, that Holmes rushes to lift up from a deadly trap. You find that there are at least 15 stories around adultery and Holmes is sympathetic to many of its champions. You wonder why he keeps a framed picture of a homosexual soldier and an unframed one of an American preacher who stood in the most famous adultery trial in the 19th Century. Explore further and you find Freudian mnemonics of violent sex (The Cardboard Box or The Engineer’s Thumb).

But it is not before several more readings that you discover Sherlock Holmes’ lover. Irene Adler.

Christopher Redmond’s book In Bed With Sherlock Holmes finds Adler a riveting study of the Victorian femme fatale — alternatively described by her society as a high-class tart and a fine woman of class and an intellect matching that of Holmes. Holmes is beaten only four times in his career, thrice by men and once by a woman. In A Scandal in Bohemia, Adler not only defeats him but walks by his house in disguise and greets him good night. To him ever afterwards, she would be The Woman. Holmes declines a prize from the king of Bohemia, preferring to keep Adler’s photo as a souvenir. Several Sherlockians have suggested he had an affair with her though they can’t agree whether it was before A Scandal or during 1891-94, when Holmes let the world believe he was dead and travelled as far as Tibet.

But it would have been unfair to expect the adventurous Adler to be a housewife to Holmes. That role went to the noncanonical Mary Russell, the Jewish-American girl in Laurie R. King’s The Beekeeper’s Apprentice. As the detective retires in the Sussex Downs to keep bees, he is joined by this orphan, intelligent woman who soon becomes his accomplice and eventually his wife.

(This story appears in the 19 February, 2010 issue of Forbes India. To visit our Archives, click here.)

-

Riju Ganguly

Riju GangulyThis exercise of finding "extra" meanings in the canon by reading-between-the-lines have been attempted on several occasions already. But it must be remembered that Holmes & Watson (not Sherlock & John) WERE Edwardian gentlemen who actually thought & acted in the manner in which they had been portrayed by Sir Arthur, and NOT as perceived now.

on Jul 19, 2011