Carving Up the Internet

Google and Verizon want network neutrality to end in the wireless world, so they can charge more to prioritise certain services. That idea may not be as evil as the world thinks

What we today call the Internet is a by-product of the US Army’s work, originating in the 1960s, to build themselves a robust and fault-tolerant communications network. And it was the US Army’s priorities and motives once again which led to another peculiar by-product we take for granted: “Network neutrality”.

Illustration: Minal Shetty

Illustration: Minal Shetty The term refers to the freedom for Internet-based services like Web sites or applications to connect to their users around the world without any controlling entity like ISPs, governments or telecom companies discriminating against or placing unnecessary restrictions on them. It is this freedom that allows a user to surf almost anything from any part of the world.

Google is a great example of a company that was built with the help of these principles.

Which is why it surprised and angered many when on August 8, Google announced a “joint policy proposal” with Verizon, an American ISP and telecom company, which in effect drove a splintered stake through the heart of network neutrality.

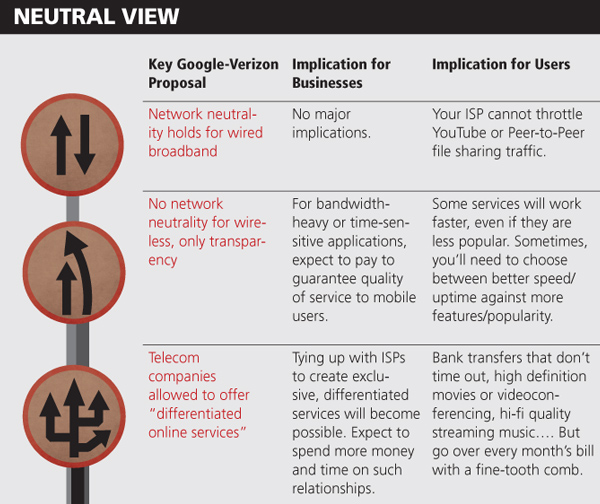

The two of them voluntarily proposed a legislative framework for the US market that broadly implied three things: Network neutrality ought to be guaranteed for wired broadband networks; it should not be for wireless networks; and that telecom companies should be allowed to offer prioritised Internet-based services for their customers.

Google’s surprising decision to exclude net neutrality from wireless airwaves was a belated admission of the fact that the future of the Internet is mobile, where it is not as strong as on the wired Internet, and that wireless operators still control things there to a large extent even today.

On the Internet, journalists, bloggers and individual users let it rip, criticising Google for selling out on the very principles that allowed it to become a success. Wired magazine, one of the Internet’s leading torch-bearers and Google’s staunchest supporters, called it a “carrier-humping, net neutrality surrender-monkey” in disgust.

But Google’s decision was more an admission of the economic reality the Internet has evolved into, than a radical departure from its principles.

Not All Packets are Created Equal

The concept of network neutrality is fused at the hip with another one: “Packet Equality”.

Due to the choices made by the US Army while building the predecessor of the Internet, the ARPANET, information is sent and received in the form of discrete “packets”. Basically, the data — any kind of data — is broken up into blocks (packets) and sent over the Internet. These packets are reassembled at the recipient’s end.

Telecom networks had to treat all packets more or less the same way, because there was no saying which ones could be lost and would then need to be resent.

This equality of packets found its way into the Internet too. So packets from your banking transaction, YouTube video, work email or online game are treated equally en route to you. Congestion is a natural result, to avoid which ISPs and telecom companies must constantly add more bandwidth capacity so packets don’t get clogged.

“All packets being equal flies in the face of quality of service. For instance VOIP packets should have more precedence than email, due to its timing urgency. Or higher security banking packets, which should not be dropped. Reducing everything to the least common denominator is not the way forward,” says Ashish Gupta, a Ph.D in Computer Science from Stanford University and co-founder of venture capital firm Helion.

In the real world we are accustomed to being prioritised almost everywhere — roads, restaurant queues, air travel, department stores. The criteria for this prioritisation ranges from money to job titles, urgency, security or loyalty. For instance, your road travel time will be very different if you’re in a large truck, an ambulance, a Ferrari or an auto-rickshaw. And if you’re willing to pay to drive on a private toll road, it will differ even more. SMSes sent to you by your friend are delivered faster than those sent by a real estate broker or restaurant.

Now precisely because the Net is different, it has given rise to so many innovative companies. This is why entrepreneurs are concerned about the imminent collapse of network neutrality. They fear fat purses rather than big brains will rule the roost once this happens.

Is This the End of Disruptive Innovation?

Start-ups fear they will need to pay telecom companies fat sums to guarantee fast speeds for their customers, or risk being seen as slow and ineffective. In the same manner, truly disruptive innovations could be nipped in the bud by incumbents with deep enough pockets to prioritise their own service so that it is delivered much faster.

There is a way to reconcile this fear. The right of a “Web” entrepreneur to reach his customers at a low cost cannot exist in opposition to the right of the telecom company to earn a profit on its investments in a reasonable time frame. A huge imbalance between the two will sooner or later either lead to a collapse of telecom companies or to a correction in the pricing equation. Telecom companies and ISPs are saddled with billions in debt used to lay cables and build networks, the plumbing that “creates” the Net.

There is a way to reconcile this fear. The right of a “Web” entrepreneur to reach his customers at a low cost cannot exist in opposition to the right of the telecom company to earn a profit on its investments in a reasonable time frame. A huge imbalance between the two will sooner or later either lead to a collapse of telecom companies or to a correction in the pricing equation. Telecom companies and ISPs are saddled with billions in debt used to lay cables and build networks, the plumbing that “creates” the Net.“It makes sense for ISPs tired of just being a pipe to reach out to guys like Google and Amazon who are making much more money by riding it,” says Gupta. He also says competition and pressure from media and regulators is likely to keep service providers from fleecing everyone left, right and centre.

In India for instance, with both competition and regulation being extremely intense, it’s unlikely that any telecom company can get away with blatant disregard for network fairness. “At this point our focus is limited to the USA. We are certainly not of view to import it to other countries due to each one’s different market, political and legal frameworks,” says Richard Whitt, senior policy counsel with Google.

Meanwhile, entrepreneurs must acknowledge that if the Internet is a new and wondrous channel to reach and serve customers, somebody ought to be compensated for maintaining that in great condition. Unlimited growth opportunities at dirt-cheap costs do not exist for too long.

“Nothing is perpetually commoditised in the world. No reason why that should not be true in the bandwidth world too,” says Gupta.

(This story appears in the 10 September, 2010 issue of Forbes India. To visit our Archives, click here.)

Post Your Comment