The Great Indian FDI Conundrum

Our politicians think our problems come from being connected with the world. But Pankaj Ghemawat says, in reality, we are too little connected to the world

The United Progressive Alliance government is fond of telling us that India’s weakening macroeconomic indicators—a falling rupee, a declining stock market, rising bond yields—are the result of being tied to a weak global economy and factors external to India. But if you were to ask Pankaj Ghemawat, Anselmo Rubiralta Professor of Global Strategy at IESE Business School in Barcelona, Spain, India is not as globally connected as we think it is.

Ghemawat has constructed a broad index of international integration, the DHL Global Connectedness Index, which was first released in November 2011. Its 2012 version was released a few months ago and it shows India closer to the bottom. “This index extends beyond trade to incorporate capital, information and people flows as well, and covers 140 countries that account for 95 percent of the world’s population and 99 percent of its GDP,” says Ghemawat.

India ranks 119 out of 140 countries on the depth of global connectedness. “When it comes to trade intensity, India still ranks among the bottom 25 percent. As far as capital connectedness is concerned, it is closer to the median,” says Ghemawat.

Capital connectedness is calculated from measures of foreign direct investment (FDI) and foreign portfolio equity investment into the stock market of the country concerned. India’s decent performance on capital connectedness is primarily on account of the huge money that has come into the Indian stock market from abroad in the last decade and big outward FDI flows in the form of overseas acquisitions by Indian corporates.

If one looks at just inward FDI, the performance is dismal. As Ghemawat puts it, “In terms of inward FDI stock expressed as a percentage of GDP, India comes in the bottom 10 percent.”

FDI flows into India have also fallen in three of the last four years. For 2012-13, FDI fell by 21 percent to $36.9 billion, government data shows. The United Nations Conference on Trade and Development, in a recent release, said that FDI inflows to India fell by 29 percent to $26 billion in 2012.

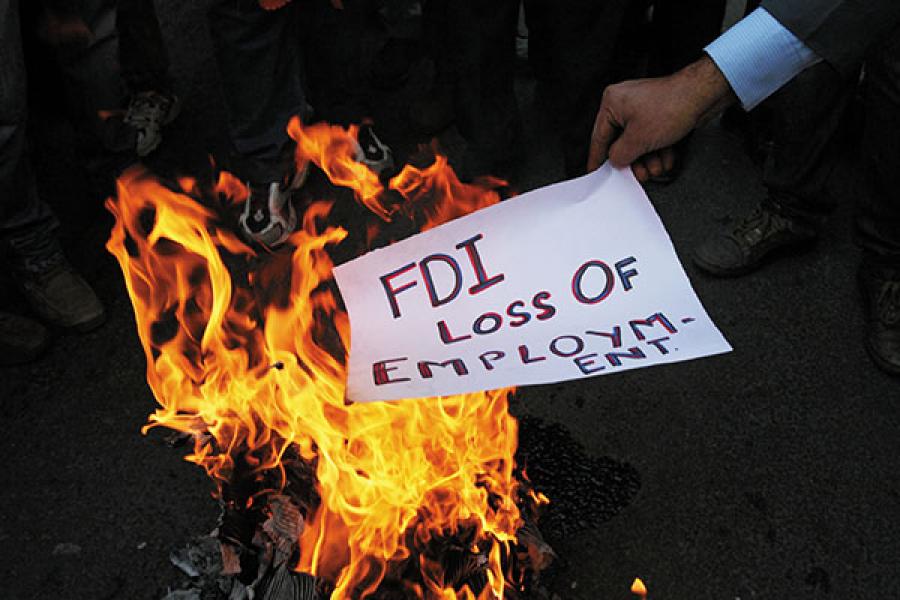

The government, faced with an unsustainable current account deficit (CAD), has been trying to encourage FDI into the country to firm up the rupee. Last year in September, the government opened up FDI in multi-brand retailing with the rider that each state can decide whether it wants companies like Walmart. Towards the middle of July 2013, the government relaxed FDI norms in 12 sectors, including telecom, insurance, asset reconstruction, petroleum refining and stock exchanges.

But since last September not a single dollar has come into the retail sector. “One reason is that investors are not sure whether the policy will continue as and when a new government comes in. Also, letting states set their own rules on such an international economic policy matter is basically unheard of elsewhere,” says Ghemawat.

He feels there is a lot that India can learn from China on this front. China started opening up its retail sector to FDI in 1992, initially with various restrictions, but ultimately allowing 100 percent FDI in 2004. This benefited them with foreign players bringing in new management practices along with supporting technology and investment capital. And we shouldn’t forget the complementarity for foreign retailers between sourcing from China (contributing to China’s export boom) and selling there.

Ghemawat argues that much of the fear about FDI in retail is exaggerated, because even with full liberalisation, foreign retailers would hardly come to dominate the Indian market. “Retail is a very local business, where an intimate understanding of customers, real estate markets, and so on, is essential to success.” He cites a recent estimate that 40 foreign players account for only about 20 percent of organised retail in China, to suggest that foreign and domestic retail could thrive side by side in India.

“Foreign retailers don’t always win out against domestic rivals,” he adds. “Electronics retailers Best Buy from the US and Media Markt from Germany shut down their stores in China in the last few years. They couldn’t compete with local rivals Gome and Suning, which had greater domestic scale and business models attuned to the Chinese market. Home Depot also exited China in 2012. But Chinese consumers gained anyway—competition against foreign retailers spurred locals to improve customer service, one of their weak points.”

Coming back to data from the Indian market, Ghemawat notes a factoid from the 2013 Economist Corporate Network Asia. The nominal GDP of India grew by 12.6 percent in 2012. In comparison, the sales of MNCs (mainly Western) in India grew by only 6.3 percent. “While this could be viewed as positive regarding Indian firms, a difference of such a big magnitude is probably reflective of a lack of openness.”

There are multiple reasons for India’s poor showing on these indicators. India regularly figures in the bottom tier of countries in terms of the extent to which its policies promote trade. In the World Economic Forum’s 2012 Global Enabling Trade Index, India figures in the bottom tier. On market access parameters in particular, it figures third from last on a list of 132 countries. Ghemawat also cites the OECD’s FDI restrictiveness index which he has inverted into the FDI Friendliness Index. “India again figures among the bottom 10 percent of 50 countries in terms of the extent to which it encourages FDI.” No amount of ministerial cajoling of potential foreign investors is likely to outweigh the impact of such protectionist policies.

When it comes to the supply of transport, energy and ICT (information, communications technology), India is 84th on the list. This lack of infrastructure is the single biggest hindrance to doing business in India, feels Ghemawat. This has also kept foreign investors away.

Given India’s weak health and basic education infrastructure (where it is 101st on the list), India remains low on productivity, which is an important factor for any foreign investor.

In the World Bank’s ranking of countries on Ease of Doing Business, India ranks 132; and stands at 173 for the ease of starting a new business.

The spate of recent scams also has not helped the way India is viewed abroad. There is significant evidence to show that corruption hampers trade. Says Ghemawat: “According to one study, an increase in corruption levels from that of Singapore to that of Mexico has the same negative effect on inward foreign investment as raising the tax rate by over 50 percentage points.” India stood at 94th position in Transparency International’s 2012 Corruption Perception Index. “Given this, tackling corruption has to be a priority,” adds Ghemawat.

The moral of the story is that although India is much more open than it used to be 20 years ago, there is a lot that still needs to be done. Ghemawat says, “There is a strong positive correlation across countries between the depth of a country’s global connectedness and measures of its prosperity, such as its GDP per capita and its ranking on the UN’s Human Development Index. To be sure, correlation is not the same as causation, but statistical analysis indicates that after controlling for initial income levels, countries with deeper global connectedness have tended to grow faster than less-connected countries.”

The point is further buttressed by the list of countries that top the 2012 DHL Global Connectedness Index. These countries are the Netherlands, Singapore, Luxembourg, Ireland, Switzerland, the United Kingdom, Belgium, Sweden, Denmark, and Germany. In the recent past some of these countries have been caught up in the aftermath of the financial crisis, but it’s important not to let recent growth rates overshadow measures of current prosperity, on which all of these countries far surpass India.

Ghemawat gives the example of the Indian information technology sector. “Ask this simple question to yourself: ‘Would Indian IT companies have been as globally competitive if we had protected them from international competition?’ The answer of course is no. But that is the case with the business services sector. There is a huge protective moat around it. This, despite the fact that the sector has a huge potential to create jobs.”

And he backs his argument with numbers. “Although some services (like haircuts) will always be delivered locally, liberalising trade in services alone could boost global GDP by 1.5 percent.” In India’s case, opening up business services—which can be outsourced over greater distances—is even more important, given that we don’t trade much with our neighbours. “For example, Indian trade with Pakistan, according to one study, is only 2 to 4 percent of what it might be under friendlier circumstances. The rest of India’s neighbours are relatively small and poor, presenting limited opportunities compared with, for example, the benefits China realised by tying into Japanese and Korean production networks.

It is neither exaggerated nor xenophobic to say that one of India’s key structural problems is that it is located in a difficult neighbourhood,” says Ghemawat.

Countries tend to trade the most with their neighbours. Ghemawat explains, “All else being equal, if you cut the distance between a pair of countries by half, their trade volume will go up almost 200 percent. Add a common border, and trade rises another 60 percent. That’s why more trade happens within world regions than across them, and the US’s top export destinations are Canada and Mexico.”

In India’s case, at least over the short-to-medium term, trading primarily with neighbours won’t be workable (though Ghemawat does urge India to take the lead on regional integration in South Asia). Hence, India will be forced to focus on distant markets. One exception he notes is how, recently, China became India’s biggest trading partner, overtaking the United States. But Ghemawat feels that caution is in order. “India runs a huge trade deficit with China and exports mainly primary products there: Cotton, copper and iron ore account for nearly one-half of the total. Given the limited progress the US has made in rebalancing its trade with China, it’s hard to see what India might accomplish within any reasonable timeframe,” he says. Trade deficit is the difference between imports and exports.

Ghemawat also feels that India has a lot to gain by encouraging trade within states. “I have been trying unsuccessfully for years to get hold of data on trade between Indian states,” he says. “India has a lot to gain by encouraging and increasing trade between states. As the former chairman of Suzuki once put it to me, what India needs is not external trade liberalisation but internal trade liberalisation. And I heard Ratan Tata say something similar about the need for more integration and fewer barriers within India. For a large country, the potential gains from internal trade are typically much larger than those from international trade,” Ghemawat concludes.

(This story appears in the 20 September, 2013 issue of Forbes India. To visit our Archives, click here.)

-

Ayush

AyushIndia can reach great heights if only we can stop bickering among ourselves over petty matters and for once decide over things as one nation. It has the potential, resources, manpower, space and economic power. All it lacks is a will to achieve greatness.

on Sep 21, 2013 -

Jacob

JacobFDI in retail should have been limited to 10-25% not 51%. Allowing 51% in 2013 is too big a step for the tabloid media to handle.

on Sep 12, 2013