Toasting the humble beginnings, grit and a burning desire to excel of small-town founders

The latest issue of Forbes India takes the small-town to startup saga forward, into the digital age, by shining a light on a clutch of new-age entrepreneurs with origins in Indian villages and towns

“Sam Walton’s first store was a second-rate store in a second-rate town in what no one would have classified as a first-rate state.”

That line from Giants of Enterprise: Seven Business Innovators and the Empires they Built by Harvard Business School Professor Richard S Tedlow sums up succinctly the Walmart founder’s strategy to build the retailing chain across small-town America. The ‘second-rate town’ was Rogers, in Arkansas, with a population of some 8,000 back in 1962.

As Walton himself wrote in his autobiography Made in America: “As an old-time small-town merchant, I can tell you that nobody has more love for the heyday of the smalltown retailing era than I do.” The Wal-Mart strategy was, as Walton put it, “simply to put good-sized discount stores into little one-horse towns which everybody else was ignoring”.

That Walton may have been born away from the urban outposts—Kingfisher, Oklahoma—and that his family of farmers moved from one small town to another in his early years may have something to do with his dime-store outlook. That think-small vision is responsible for Wal-Mart today being worth over $400 billion and racking up $573 billion in revenue in 2022 with operating cash flows of $24.2 billion.

Back in India, Mumbai, Bengaluru, Hyderabad and Gurugram may be where India’s top industrialists are based; but many first-generation entrepreneurs have had village/small-town origins that played a key role in their relentless pursuit of growth.

Dhirubhai Ambani, for instance, spent his formative years in Chorwad, a coastal village near Junagadh and Somnath in Gujarat, before moving to Aden in Yemen when in his teens; and eventually returned to India to flag off his entrepreneurial journey that began with textiles. Elsewhere, Prathap C Reddy, pioneer of the corporate hospital chain Apollo, was born into a farming family in the village of Aragonda, in Chittoor, Andhra Pradesh.

In this fortnight’s edition, Rajiv Singh takes the small town to startup saga forward, into the digital age, by shining a light on a clutch of new-age entrepreneurs with origins in Indian villages and towns.

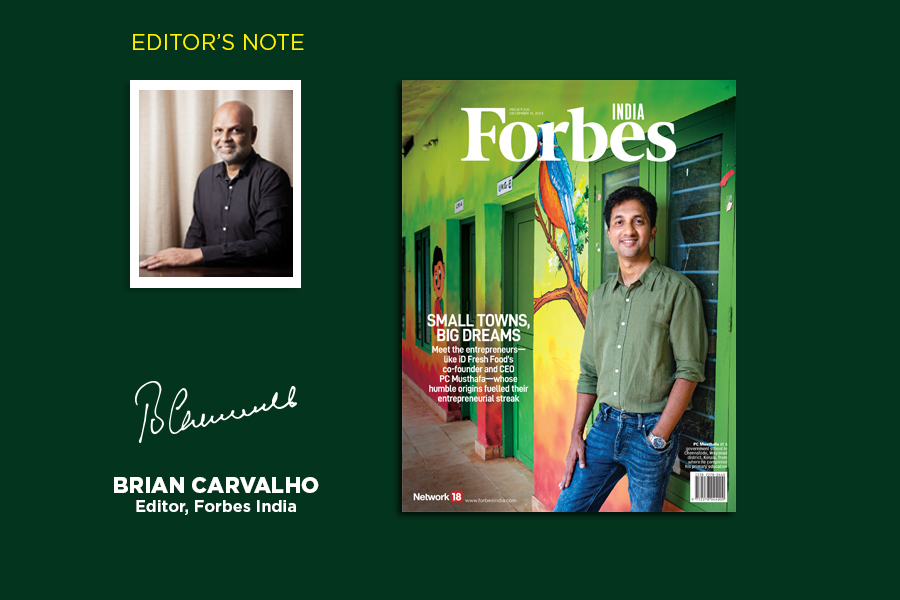

On the cover is PC Musthafa, founder & CEO of a company that’s become synonymous with idli and dosa batter, iD Fresh Food. Born in the scenic village of Chennalode in Kerala’s Wayanad district, Musthafa grew up without roads, electricity and schools; he had to travel six kilometres for a primary education out of the village. The founder of a company that last raised ₹507 crore (in 2022) tells Singh about the early difficult days: His father earned daily wages of ₹12 working 13 hours on a ginger farm; and his mother would skip a meal to ensure food on the table for him and his three siblings.

Those tough days hold Musthafa in good stead as he expands into new markets and categories, even as iD Fresh continues to lose money. “The village way of life gives you values, humility—and jugaad,” he says. For more on the iD Fresh journey from Wayanad to international markets like the US and the UK, turn to ‘A Batter Option’.

This issue is packed with many more stories of humble beginnings, grit and a burning desire to excel. Consider, for instance, the serendipitous food foray of Agra-born Vishal Jindal. A hedge fund manager in 2012, Jindal was devouring kebabs and tandoori chicken on a visit to his birthplace. It’s in the city renowned for its local delicacies that he hit upon the idea of starting a pan-India kebab and biryani chain. Result? An investor turned entrepreneur and a venture called Biryani By Kilo was born. For more on that recipe, go to ‘Rice and Spice’.

Brian Carvalho

Editor, Forbes India

Email: Brian.Carvalho@nw18.com

Twitter ID: @Brianc_Ed

(This story appears in the 15 December, 2023 issue of Forbes India. To visit our Archives, click here.)