Do not chase perfection in spontaneous communication: Matt Abrahams

The Stanford Graduate School of Business lecturer explains why good enough is great when it comes to speaking in the moment, focus is critical, and attention the most precious commodity in the world

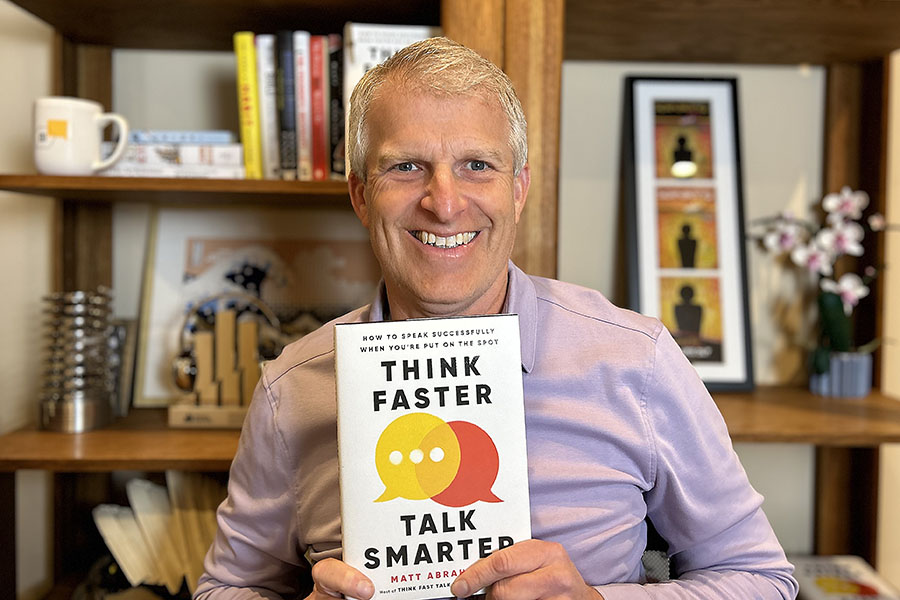

Matt Abrahams is an author and a lecturer in organisational behaviour at the Stanford Graduate School of Business.

Matt Abrahams is an author and a lecturer in organisational behaviour at the Stanford Graduate School of Business.

Matt Abrahams is a lecturer in organisational behaviour at the Stanford Graduate School of Business. He hosts Think Fast, Talk Smart: The Podcast and is the author of Think Faster, Talk Smarter: How to Speak Successfully When You’re Put on the Spot. In an interview with Forbes India, he unpacks the nuances of spontaneous speaking—the need for structure and focus, perks of listening deeply, ways to fight anxiety, and so on. Edited excerpts:

Q. Why is spontaneous speaking a scary proposition for most of us?

If you think about it, most of our communication happens in the moment. It’s not a planned presentation or a scripted pitch or a meeting with agenda. It’s everything we do day to day—giving feedback, making small talk, introducing yourself, apologising, and even answering questions. It’s scary because we don’t feel prepared, and we feel a lot of pressure to do it right immediately. This is a topic that has been a part of my life for as long as I can remember. My last name is Abrahams. Starting with ‘Ab’, I was always called on first in school.

About nine years ago, the deans at Stanford Graduate School of Business asked me to help with a problem. Many of our amazingly bright students were having trouble answering cold calls when a professor called on them. They knew the answer, but were struggling to formulate their thoughts. They asked if I could create content that would help. So, I combined my experience as well as did a deep dive into several fields of study—psychology, anthropology, neuroscience, and improvisation—and came up with a methodology which is in the book.

Q. Dry throat, sweaty hands, pounding heart, and so on—our bodies respond in unpredictable ways when nerves get the better of us. How best can we check the anxiety spiral?

I would argue it’s not unpredictable at all. In fact, close to 85 percent of people who get nervous speaking in front of others respond in similar ways. It’s the fight or flight response. There are many things we can do to manage our innate anxiety. It’s about managing symptoms and sources. Symptoms are the things we physiologically and mentally experience. We can manage them by taking deep belly breaths like you do in tai chi or yoga, and make exhalations twice as long as inhalations. We can do things like taking some sips of warm water to get rid of our dry mouth and reactivate our salivary glands. We can also address some of the sources of anxiety—for example, we can focus on the present rather than worrying about not achieving the goals we set out to achieve when we communicate. We can do that by doing something physical like walking around the building, counting backwards from one hundred by a challenging number like 17, listening to a song or playlist, or saying a tongue-twister.

Q. Why should we strive to be just mediocre?

Many of us, in our communication, especially when spontaneous, want to do it right. However, there are better ways and worse ways, but there is no one right way to communicate. The pressure we put on ourselves really makes it unlikely that we will do our best. We can use an analogy here: Think of your brain as a computer. If you are running lots of apps or have lots of windows open, your computer’s bandwidth is being stretched and it can’t run efficiently. Your brain’s the same way—if you are intensely judging and evaluating and trying to do it right, then you have less bandwidth to actually do it well at all. So, maximise mediocrity—just get it done. It actually helps us be more focussed on the connection we are striving for in our communication rather than the perfection. So, if you are in the moment, answering a question, just focus on answering a question rather than trying to give the right answer. Just give your feedback rather than striving for the best feedback.

Also read: Digital communication is the new power skill: Erica Dhawan

Q. Are heuristics bad?

Heuristics are necessary. These are shortcuts we leverage to help us make quick, important decisions. However, when we lock ourselves into a heuristic way of thinking, especially in spontaneous situations, we can actually restrict what’s possible in the moment. For example, imagine you and I leave a meeting, and you asked me how I thought you did. Using heuristic thinking, I lock myself into my feedback heuristics and give you all the things that didn’t go well or could have gone better. But if I had been more open—less locked into my feedback heuristic—I might not have missed that what you really wanted was support. By giving you constructive feedback, I might actually be acting against the support that you need. So creativity is limited because we are not in the moment, paying attention to what’s needed—our heuristics blind us.

Q. How can you build ‘structure’ into in-the-moment speaking situations?

‘Structure’ is critical. It’s a logical connection of ideas. The most common structure people are familiar with includes problem, solution, benefit. This structure is very common in advertisements. You start by explaining a problem, next give a solution as a way of improving upon a current challenge, and then provide the benefit that comes as a result. Our brains are wired to process structured information, not lists. So, by using structure we make it easier on our audience to understand, remember, and relay our messages. We should practise different types of structure

Q. What’s the F-word of spontaneous speaking?

The F-word is ‘focus’. Many of us, as we speak in the moment, take our audience on a journey of our discovery and what it is we are saying as we are saying it. In other words, we just list and ramble. Focus is critical. Attention is the most precious commodity in the world. If we ramble, we lose our audience’s attention. The best ways to focus your message is to focus on salience and relevance of your content for your audience. Beyond relevance, you need to have a clear goal—what you want your audience to know, feel, and do. The goal can help you prioritise what it is that you are saying. And finally, you need to focus on the language you use; remove complex language, acronyms, and jargon.

Q. Are better listeners necessarily better communicators?

I think so. If you want to be a better writer, you have to read a lot. If you want to be a better communicator, then you have to listen and practise communicating. Listening helps you tune into what is needed in the moment. We can all get better at listening by focusing on the bottom line, not the top line. Most of us just listen to the gist of what somebody is saying rather than listening to the heart of what is being said. We need to focus, be present, and give ourselves permission to really listen not just to what is said but how it is said and the context in which it is said.

Q. Tips for handling impromptu questions, say during a job interview…

When you are answering questions, especially for a job interview, you should be thinking about potential themes you want to get across before you enter the situation. And you should come up with support for each of those themes in advance. Let’s say my theme is that I want to suggest that I am a good product manager. Then, I come up with examples and stories of how I managed projects and some data of my success as a product manager. And I have those ready. So, when the question comes, I simply answer it in a structure.

There’s a great structure I like for answering questions called ADD—answer the question, give a detailed example, and then describe the relevance. So, if someone asks what skill you bring to this job, I might say I am an expert and a really well-seasoned product manager. In my last project, I managed a team of 25 people across multiple continents, and we finished the project in less time and saved more money than any other project that year. So, I gave an answer, a concrete example, and then I explained the relevance.