The economic potential of women self-help groups

Leveraging the potential of women self-help groups for economic revival calls for bridging the digital divide, building scalable programmes, and creating targeted interventions for the most vulnerable

Jugni says she is “as illiterate as a buffalo”, speaking in Hindi as she lays out a plastic mat next to a farm where a few goats are tied to trees. She belongs to the Garasia tribe in the Sirohi district of Rajasthan, and is meeting with five other members of her self-help group (SHG) in July after a gap of four months. Their functioning had come to a complete halt during the lockdown, and there was a lot of work to do. “We could not go to the market to sell our produce, and used to give it to a middleman who collected it from our homes. So the bhindi [okra] we used to sell for ₹20 a kilo went for as low as ₹7 per kilo during the lockdown,” she says, over a video call on a borrowed smartphone. She owns a feature phone, and is just warming up to virtual meetings. Jugni, one of the founding members of the Chetna Rani Mahila SHG, says she has come a long way from getting women to save ₹10 each week to be able to get electric supply to their fields two decades ago. Today, the 13 women in her group are able to save up to ₹80,000 a year and take small loans from local cooperatives for their farming and animal husbandry ventures. Their financial literacy, visible in the meticulous accounts maintained in notebooks, has been learnt entirely through experience. Digital knowledge never seemed like a priority, until now, and Jugni is willing to learn, if adapting to change is what it takes to survive in the wake of the pandemic. “Most people have a feature phone and a bank account in these villages. Only a few members in about 150-odd women’s groups out of 500 in this area are educated and own a smartphone. After the movement of SHGs was severely restricted during the lockdown, we are working towards piloting a digital literacy project among these 150-odd groups in August,” says Richa Audhichya, a social activist who works with local women SHGs through her organisation Jan Chetna Sansthan. “It’s time, because these women can’t stop just because there is uncertainty due to the pandemic.”

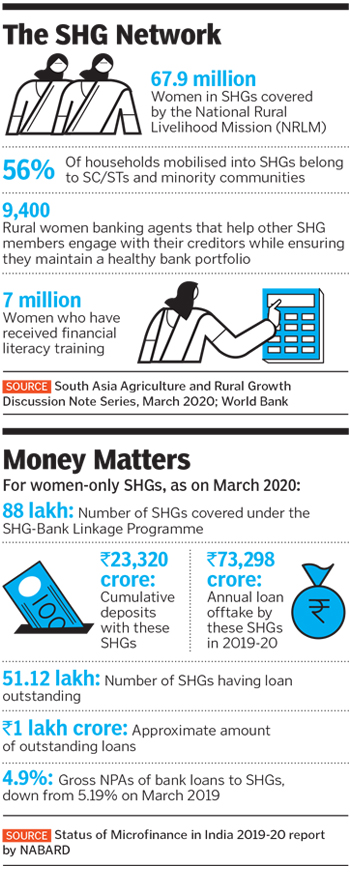

India’s network of rural SHGs—where women from similar socio-economic backgrounds pool in their savings and manage their credit interests with the principles of solidarity and mutual interest—has grown over the years, enabling women to be enterprising, take risks, earn financial independence and seek greater participation in the decisions taken in their homes and villages. India has over 68 million women working as part of SHGs, and like most industries and sectors they are turning the Covid-19 challenge into an opportunity.

“The government, through the National Rural Livelihood Mission [NRLM], has given them a capitalisation support of ₹10,200 crore, and these SHGs have also earned bank credit of over ₹2.9 lakh crore,” says Alka Upadhyay, additional secretary, Union Ministry of Rural Development (MoRD). She points to the low non-performing asset (NPA) rates of women-led SHGs to emphasise that they can play a critical role in India’s economic rebuilding story. According to the National Bank for Agriculture and Rural Development (Nabard), the gross NPA rate for women-led SHGs is around 4.9 percent as of March 2020, which is half the rate of NPAs in banks.

“SHG women have been proving to banks that they are serious customers, and based on how this network has demonstrated its capabilities during Covid-19, it makes sense to nudge them towards a higher-order economic activity by making available more community funds and credit linkages. Digitising the SHG channels is another big step in this direction” says Upadhyay.

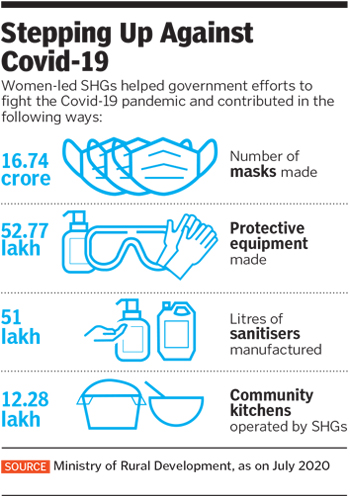

She is referring to how the SHGs led by women supported the government with essentials to fight the pandemic. According to the MoRD, since March, women have made about 17 crore masks, 53 lakh protective equipment and 51 lakh litres of sanitisers. Leveraging their skill sets and using technology to connect with each other and deliver in record time during the lockdown, these SHGs are now helping governments address issues faced by migrant labourers in their respective states.

For instance, Ruby Khatun (25)from the Maheshpur village in Jharkhand, a member of the Barkat Mahila SHG who runs a grocery store for a living, worked tirelessly through the lockdown and after. As the chief bookkeeper of all the SHGs in her village, she helped women undertake digital bank transactions, health or vehicle insurance and mobile recharge payments. As part of the state’s helpline, she helped over 50 migrant workers reach home.

“I used to take calls at all times of the day and night, listening to migrant labourers who were stranded and wanted to come back home. I used to arrange food for them through our community kitchens. There are seven SHGs in our village and each is working to get each other back on our feet. I have created WhatsApp and social media groups for all of them to stay informed and connected,” she says.

Kumar Vikash, an official from the Jharkhand State Livelihood Society, tells Forbes India that over 7,000 community kitchens run by women SHGs in Jharkhand served 4 crore meals between April and June.

They invested a total of about `38 crore in the rural economy by procuring vegetables and groceries from local farmers and vendors, and the government paid them `10 per plate of food made in the community kitchens. After the lockdown, they are collecting data through a mobile app launched by the state from the 7 lakh-odd migrant labourers who have returned to Jharkhand, getting details about their skills sets, salary, knowledge of agricultural work, eligibility to social security schemes etc.

“If government officials are able to sit in Ranchi and ensure last-mile coverage of villages in the Saranda forest in West Singhbhum, it is due to the institutionalised system of SHGs,” Vikash says. He explains that many of these women are taking fresh loans to start small-scale enterprises, given that their husbands, who were migrant labourers, have returned and want to remain in the village. “These groups are key in helping us create local livelihood opportunities and get the rural economy back on track.”

Chinks in the Armour

India’s network of rural SHGs—where women from similar socio-economic backgrounds pool in their savings and manage their credit interests with the principles of solidarity and mutual interest—has grown over the years, enabling women to be enterprising, take risks, earn financial independence and seek greater participation in the decisions taken in their homes and villages. India has over 68 million women working as part of SHGs, and like most industries and sectors they are turning the Covid-19 challenge into an opportunity.

“The government, through the National Rural Livelihood Mission [NRLM], has given them a capitalisation support of ₹10,200 crore, and these SHGs have also earned bank credit of over ₹2.9 lakh crore,” says Alka Upadhyay, additional secretary, Union Ministry of Rural Development (MoRD). She points to the low non-performing asset (NPA) rates of women-led SHGs to emphasise that they can play a critical role in India’s economic rebuilding story. According to the National Bank for Agriculture and Rural Development (Nabard), the gross NPA rate for women-led SHGs is around 4.9 percent as of March 2020, which is half the rate of NPAs in banks.

“SHG women have been proving to banks that they are serious customers, and based on how this network has demonstrated its capabilities during Covid-19, it makes sense to nudge them towards a higher-order economic activity by making available more community funds and credit linkages. Digitising the SHG channels is another big step in this direction” says Upadhyay.

She is referring to how the SHGs led by women supported the government with essentials to fight the pandemic. According to the MoRD, since March, women have made about 17 crore masks, 53 lakh protective equipment and 51 lakh litres of sanitisers. Leveraging their skill sets and using technology to connect with each other and deliver in record time during the lockdown, these SHGs are now helping governments address issues faced by migrant labourers in their respective states.

For instance, Ruby Khatun (25)from the Maheshpur village in Jharkhand, a member of the Barkat Mahila SHG who runs a grocery store for a living, worked tirelessly through the lockdown and after. As the chief bookkeeper of all the SHGs in her village, she helped women undertake digital bank transactions, health or vehicle insurance and mobile recharge payments. As part of the state’s helpline, she helped over 50 migrant workers reach home.

“I used to take calls at all times of the day and night, listening to migrant labourers who were stranded and wanted to come back home. I used to arrange food for them through our community kitchens. There are seven SHGs in our village and each is working to get each other back on our feet. I have created WhatsApp and social media groups for all of them to stay informed and connected,” she says.

Kumar Vikash, an official from the Jharkhand State Livelihood Society, tells Forbes India that over 7,000 community kitchens run by women SHGs in Jharkhand served 4 crore meals between April and June.

They invested a total of about `38 crore in the rural economy by procuring vegetables and groceries from local farmers and vendors, and the government paid them `10 per plate of food made in the community kitchens. After the lockdown, they are collecting data through a mobile app launched by the state from the 7 lakh-odd migrant labourers who have returned to Jharkhand, getting details about their skills sets, salary, knowledge of agricultural work, eligibility to social security schemes etc.

“If government officials are able to sit in Ranchi and ensure last-mile coverage of villages in the Saranda forest in West Singhbhum, it is due to the institutionalised system of SHGs,” Vikash says. He explains that many of these women are taking fresh loans to start small-scale enterprises, given that their husbands, who were migrant labourers, have returned and want to remain in the village. “These groups are key in helping us create local livelihood opportunities and get the rural economy back on track.”

Chinks in the ArmourExperts point out that while there has been progress, policies and interventions for SHGs need to align more closely with community needs on the ground, and implementation must be tracked such that it reaches the bottom 10 percent of people who are the most vulnerable sections of society. An example is one of the announcements in the economic stimulus package by Finance Minister Nirmala Sitharaman in May that included doubling collateral-free loans to women SHGs from ₹10 lakh to ₹20 lakh. While the directive extends to women SHGs on paper, the average ticket size of loans taken by these women is just around ₹1.80 lakh.

“It doesn’t actually impact them very much since SHG loans are relatively small. What is likely to happen is that even slightly larger requests from this cohort not be prioritised [by banks], because it is not part of the directive and nobody is counting the targets on that. So it’s an invisible space that these women fall into as a result,” says Gayatri Acharya, lead economist at the World Bank, which is co-financing the NRLM.

Her view is seconded by M Srikanth, associate professor and head, centre for financial inclusion and entrepreneurship at the National Institute of Rural Development and Panchayat Raj (NIRDPR). He believes there is a need to understand the psyche of women who become members of SHGs.

“Most of these women are below the poverty line, so they come together as a group, mobilise savings and access finance from banks to start a traditional business. Gradually, when they cross the poverty line, have brick-and-mortar homes and other basic lifestyle amenities, they mostly won’t be interested in taking their businesses to the next level and become big-scale entrepreneurs,” he says. “So they do not want financial availment of ₹10 lakh and ₹20 lakh.”

Upadhyay admits that the average loan ticket size and threshold of collateral-free loans in the policy announcement is inconsistent, but says that it is part of the government’s long-term plan to enable women SHGs to create larger, more sustainable and self-sustaining enterprises.

“As I recall, and I could stand corrected on the figure, about 30 percent of SHGs take loans between ₹5 lakh and ₹10 lakh. This is part of our vision of creating large regional women-led producer collectives that will help them leverage better marketing possibilities and create high-value economic enterprises,” she says, explaining that around 86,000 producer groups have already started functioning. Between this year and next, the government plans to build at least 60 successful collectives that start with an SHG base but break-even due to the scale of their operations and do not require government support anymore.

Experts suggest that increasing government procurement from SHGs will also help them scale up. A case in point is how the State Rural Livelihood Mission (SRLM) in Kerala, called Kudumbashree, coordinated with other government departments to encourage high-value public sector contracts to firms owned by SHG members.

One example, according to the South Asia Agriculture and Rural Growth Discussion Note Series, March 2020, published by the World Bank, is how the social welfare department in Kerala procures a dietary supplement called Nutrimix for its anganwadis (community health centres). It is provided as part of the take-home ration under the Integrated Child Development Services (ICDS) scheme to children between six and 36 months of age. “Today, 242 Kudumbashree-units—owned and operated by more than 2,000 women—supply Nutrimix to 33,000 aanganwadis across Kerala, with a collective annual turnover of over ₹100 crore,” the document states.

Credit Where it’s Due

“It doesn’t actually impact them very much since SHG loans are relatively small. What is likely to happen is that even slightly larger requests from this cohort not be prioritised [by banks], because it is not part of the directive and nobody is counting the targets on that. So it’s an invisible space that these women fall into as a result,” says Gayatri Acharya, lead economist at the World Bank, which is co-financing the NRLM.

Her view is seconded by M Srikanth, associate professor and head, centre for financial inclusion and entrepreneurship at the National Institute of Rural Development and Panchayat Raj (NIRDPR). He believes there is a need to understand the psyche of women who become members of SHGs.

“Most of these women are below the poverty line, so they come together as a group, mobilise savings and access finance from banks to start a traditional business. Gradually, when they cross the poverty line, have brick-and-mortar homes and other basic lifestyle amenities, they mostly won’t be interested in taking their businesses to the next level and become big-scale entrepreneurs,” he says. “So they do not want financial availment of ₹10 lakh and ₹20 lakh.”

Upadhyay admits that the average loan ticket size and threshold of collateral-free loans in the policy announcement is inconsistent, but says that it is part of the government’s long-term plan to enable women SHGs to create larger, more sustainable and self-sustaining enterprises.

“As I recall, and I could stand corrected on the figure, about 30 percent of SHGs take loans between ₹5 lakh and ₹10 lakh. This is part of our vision of creating large regional women-led producer collectives that will help them leverage better marketing possibilities and create high-value economic enterprises,” she says, explaining that around 86,000 producer groups have already started functioning. Between this year and next, the government plans to build at least 60 successful collectives that start with an SHG base but break-even due to the scale of their operations and do not require government support anymore.

Experts suggest that increasing government procurement from SHGs will also help them scale up. A case in point is how the State Rural Livelihood Mission (SRLM) in Kerala, called Kudumbashree, coordinated with other government departments to encourage high-value public sector contracts to firms owned by SHG members.

One example, according to the South Asia Agriculture and Rural Growth Discussion Note Series, March 2020, published by the World Bank, is how the social welfare department in Kerala procures a dietary supplement called Nutrimix for its anganwadis (community health centres). It is provided as part of the take-home ration under the Integrated Child Development Services (ICDS) scheme to children between six and 36 months of age. “Today, 242 Kudumbashree-units—owned and operated by more than 2,000 women—supply Nutrimix to 33,000 aanganwadis across Kerala, with a collective annual turnover of over ₹100 crore,” the document states.

Credit Where it’s DueUpadhyay says the MoRD does not believe in the subsidy regime for SHGs anymore, and is working toward strengthening bank credit linkages to make the process more transparent, and the groups more economically independent in the longer term.

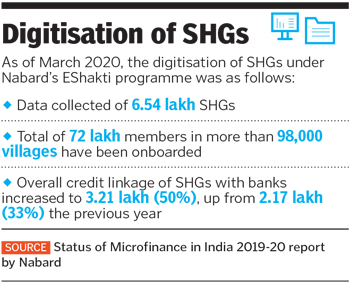

At the core of this plan is digital and financial inclusion through the EShakti and the SHG-Bank Linkage Programme (SHG-BLP) led by Nabard, which is trying to empower SHGs through technology. Nandini Ghose, deputy general manager at Nabard, who works on the EShakti programme, says it is present in about 254 out of the 700 districts in the country, and the fifth phase of the programme will start soon.

“We collect financial data every month that banks can access to view the credit history of a particular SHG. The banks can then take a decision based on the grading of the SHG and sanction loans through the portal itself. This makes the process hassle-free and less time-consuming,” she says. Ghose says they also collect demographic data of groups and individual members, covering metrics such as benefits women receive from existing social security schemes, how many times they have taken loans, outstanding amounts, repayment patterns, and loans availed from community-based institutions.

According to Acharya, in the long term, individual records being digitised and accessible will enable women with healthy credit histories to opt out of SHGs. “Right now, it is the group-based payment records that make banks feel confident, but eventually we hope that the individual woman is empowered to understand what she needs to do in order to effectively engage with banks, and banks have enough confidence to lend directly to her,” she says.

Banks are also engaging with rural communities by appointing women as banking correspondent sakhis who will liaison with SHGs, which experts view as both an employment source and a confidence-building space for other women to be part of the banking ecosystem.

There are approximately 9,400 women bank sakhis in India. Sushma Devi is one such banking correspondent from a remote village in Bihar’s Aurangabad district, whose monthly earnings through commissions have been around ₹8,031. During the lockdown, she worked from 8 am to 8 pm every day, providing banking transaction support to people, and also personally visiting homes of people who were old or unwell. In the month of April, she made 1,967 transactions worth approximately ₹81 lakh.

Sushma is part of a network of 1,085 bank sakhis in the state, who collectively did transactions worth ₹435 crore even through the lockdown, says D Balamurugan, an Indian Administrative Service (IAS) officer who is the CEO of Jeevika, the implementation agency for the NRLM in Bihar.

“Right now, the bulk of the SHG transactions still happen on paper, but we are testing a mobile application with 5,000 women on a pilot basis to take the process completely online,” he says.

Acharya, however, says while private banks are showing inclination to work with women banking agents, field surveys indicate that “women continue to be poorly represented in the banking correspondent agent network compared to men, even though women form over 54 percent of the Pradhan Mantri Jan Dhan Yojana account holders”. Women represent only 8 percent of all banking correspondents in the country.

The MoRD has, therefore, engaged with banks to train, appoint and support women banking correspondents, and has set an ambitious target of deploying 1 lakh SHG members by 2023-24. Another focus is to ensure that the women use and engage with their bank accounts regularly so that they don’t remain dormant. “That is an essential part of the ongoing financial inclusion story,” Acharya says.

A Silver Lining

At the core of this plan is digital and financial inclusion through the EShakti and the SHG-Bank Linkage Programme (SHG-BLP) led by Nabard, which is trying to empower SHGs through technology. Nandini Ghose, deputy general manager at Nabard, who works on the EShakti programme, says it is present in about 254 out of the 700 districts in the country, and the fifth phase of the programme will start soon.

“We collect financial data every month that banks can access to view the credit history of a particular SHG. The banks can then take a decision based on the grading of the SHG and sanction loans through the portal itself. This makes the process hassle-free and less time-consuming,” she says. Ghose says they also collect demographic data of groups and individual members, covering metrics such as benefits women receive from existing social security schemes, how many times they have taken loans, outstanding amounts, repayment patterns, and loans availed from community-based institutions.

According to Acharya, in the long term, individual records being digitised and accessible will enable women with healthy credit histories to opt out of SHGs. “Right now, it is the group-based payment records that make banks feel confident, but eventually we hope that the individual woman is empowered to understand what she needs to do in order to effectively engage with banks, and banks have enough confidence to lend directly to her,” she says.

Banks are also engaging with rural communities by appointing women as banking correspondent sakhis who will liaison with SHGs, which experts view as both an employment source and a confidence-building space for other women to be part of the banking ecosystem.

There are approximately 9,400 women bank sakhis in India. Sushma Devi is one such banking correspondent from a remote village in Bihar’s Aurangabad district, whose monthly earnings through commissions have been around ₹8,031. During the lockdown, she worked from 8 am to 8 pm every day, providing banking transaction support to people, and also personally visiting homes of people who were old or unwell. In the month of April, she made 1,967 transactions worth approximately ₹81 lakh.

Sushma is part of a network of 1,085 bank sakhis in the state, who collectively did transactions worth ₹435 crore even through the lockdown, says D Balamurugan, an Indian Administrative Service (IAS) officer who is the CEO of Jeevika, the implementation agency for the NRLM in Bihar.

“Right now, the bulk of the SHG transactions still happen on paper, but we are testing a mobile application with 5,000 women on a pilot basis to take the process completely online,” he says.

Acharya, however, says while private banks are showing inclination to work with women banking agents, field surveys indicate that “women continue to be poorly represented in the banking correspondent agent network compared to men, even though women form over 54 percent of the Pradhan Mantri Jan Dhan Yojana account holders”. Women represent only 8 percent of all banking correspondents in the country.

The MoRD has, therefore, engaged with banks to train, appoint and support women banking correspondents, and has set an ambitious target of deploying 1 lakh SHG members by 2023-24. Another focus is to ensure that the women use and engage with their bank accounts regularly so that they don’t remain dormant. “That is an essential part of the ongoing financial inclusion story,” Acharya says.

A Silver LiningSrikanth of NIRDPR believes that necessity is the mother of invention, and even if women themselves have no digital knowledge, “they will either learn, or get the work done through their children, who are more well-versed with technology. Over a period of time, just like their financial literacy has improved with experience, their digital literacy will also improve”. Women are taking small but steps that are significant to them. Sangita Devi in Bihar, for example, was used to conventional paper procedures and physical work for many years. She has now warmed up to digital transactions and virtual training sessions and meetings. During the pandemic, she focussed specifically on maternal and child health, as she believes that financial stability is linked to good health. “The lockdown forced all of us to stay home, so I used to guide people over the phone and through WhatsApp and other communication apps. I learnt how to conduct virtual meetings via Zoom and Google, and in turn reached over 500 other SHG members,” she says.

Acharya says the use of technology in agriculture can also be a game changer for women SHGs. The growing number of women-led agri-tech startups globally and in India, increase in the use of precision-farming technologies by women farmers and shifting of social norms that discouraged them to be formally recognised as farmers or entrepreneurs, among other factors, are steps in the right direction.

“The specific requirements for women, and rural women in particular, would need to be understood and addressed by such technologies so that they aren’t exclusionary,” she says.

According to her, innovations coming from poorer states like Bihar and Jharkhand open up possibilities for SHGs in other states to follow suit. “It needs good policy at the state level, champions who will push it through, and investments from the Centre and the banks in particular, especially to resolve issues in banking software,” she says. “That sort of rural digital backbone has to be invested in, and that kind of investment must come from the relevant sectors and stakeholders.”

Acharya says the use of technology in agriculture can also be a game changer for women SHGs. The growing number of women-led agri-tech startups globally and in India, increase in the use of precision-farming technologies by women farmers and shifting of social norms that discouraged them to be formally recognised as farmers or entrepreneurs, among other factors, are steps in the right direction.

“The specific requirements for women, and rural women in particular, would need to be understood and addressed by such technologies so that they aren’t exclusionary,” she says.

According to her, innovations coming from poorer states like Bihar and Jharkhand open up possibilities for SHGs in other states to follow suit. “It needs good policy at the state level, champions who will push it through, and investments from the Centre and the banks in particular, especially to resolve issues in banking software,” she says. “That sort of rural digital backbone has to be invested in, and that kind of investment must come from the relevant sectors and stakeholders.”

(This story appears in the 14 August, 2020 issue of Forbes India. To visit our Archives, click here.)

Post Your Comment