How Mohit Dubey's hustle and adaptation moves Bharat with Chalo

Influenced by the constraints of growing up in a small town and disciplined by a regimented way of life in a boarding school, Mohit Dubey learnt to relate to the plight of millions. In Chalo, he has built a bus tracking and ticketing platform for Bharat and India

Mohit Dubey, Cofounder and CEO, Chalo

Image: Akashdeep Varma for Forbes India

Mohit Dubey, Cofounder and CEO, Chalo

Image: Akashdeep Varma for Forbes India1983, Harshud, Madhya Pradesh. Mohit Dubey was standing in a queue for an hour. There were many who were patiently waiting in the serpentine row for over two hours. “The sight of the neatly-lined up water buckets was fascinating,” recalls Dubey, who was nine years old then. With no water supply in Harshud, tankers used to come twice a week on Monday and Thursday. This Monday, they got delayed. The young boy, though, had little to complain about. The screeching noise of the railway track, which was close to the place where the tankers got parked, and constant chatter of the ones sweating it out in the line, kept Dubey hooked. “I used to talk and mingle a lot,” he recounts.

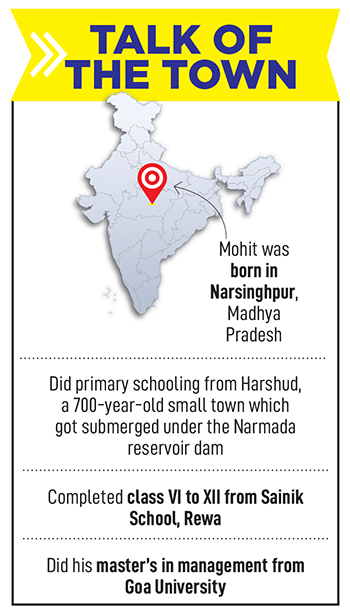

What also kept the boy busy was putting in extra hours in studies. Born in Narsinghpur in Madhya Pradesh, Dubey’s family shifted to Harshud, from where he completed his schooling till class V. “You start valuing things much early in life if you are born in a place that doesn’t have water,” says Dubey, who used to cycle six kilometres one way to reach school. “Electricity, too, was a luxury and privilege,” he says, adding that his father gave education a top priority. He was employed in an agricultural department of the state, and wanted his son to have a bright academic future.

Future definitely was the only reason why Dubey’s father decided to put him in Sainik School. Residential schools affiliated to CBSE and run by the defence ministry, Sainik Schools were slowly being looked up to as a ticket to a bright future. The one in Rewa had better infrastructure, offered impressive opportunities and boasted highly qualified teachers than what Dubey had access to till then. The boy started a new innings in class VI. “I am doing what is best for you,” the father told his son about the apparently harsh decision of exposing him to the hostel way of life at a young age. “Remember, when you grow up, you too must do what is best for you and society,” was his life-changing advice.

Future definitely was the only reason why Dubey’s father decided to put him in Sainik School. Residential schools affiliated to CBSE and run by the defence ministry, Sainik Schools were slowly being looked up to as a ticket to a bright future. The one in Rewa had better infrastructure, offered impressive opportunities and boasted highly qualified teachers than what Dubey had access to till then. The boy started a new innings in class VI. “I am doing what is best for you,” the father told his son about the apparently harsh decision of exposing him to the hostel way of life at a young age. “Remember, when you grow up, you too must do what is best for you and society,” was his life-changing advice.

Dubey’s life, indeed, was about to change dramatically. “Suddenly I was on my own,” recounts Dubey, who started getting a hang of an independent and regimented way of life. From competing with boys from the top cities to standing up to the rowdy ones who would bully him because of his short height, Dubey was learning a new way of life. “I lived with two options at the hostel for seven years,” he says, alluding to his stint at boarding schools. “Either I had to eat, or I was free to stay hungry,” he smiles, referring to lack of choice in the mess unlike home where he was pampered by his mother.

Fast forward to 2001. Dubey again had tryst with two choices. The software programmer had just got his prized US visa, and decided to spend three months with his in-laws in Bhopal before joining his overseas job. During the period, he joined a small company which provided citizen-centric services to villagers such as getting a birth certificate and a copy of land records. During one of his visits to a remote hamlet, he discovered a shocking side of the countryside: People didn’t have access to doctors; one had to wait for hours to get a bus; and many died because they couldn’t reach the city hospitals on time. Dubey dumped his US dream. “Dying due to lack of health care access is outrageous,” he said to himself, and decided to take a stab at telemedicine to solve rural India’s woes.

Fast forward to 2001. Dubey again had tryst with two choices. The software programmer had just got his prized US visa, and decided to spend three months with his in-laws in Bhopal before joining his overseas job. During the period, he joined a small company which provided citizen-centric services to villagers such as getting a birth certificate and a copy of land records. During one of his visits to a remote hamlet, he discovered a shocking side of the countryside: People didn’t have access to doctors; one had to wait for hours to get a bus; and many died because they couldn’t reach the city hospitals on time. Dubey dumped his US dream. “Dying due to lack of health care access is outrageous,” he said to himself, and decided to take a stab at telemedicine to solve rural India’s woes. The idea was to connect distant villages with district hospitals. The problem, though, was that few believed in his idea. For three years, Dubey made futile attempts to convince government officials and politicians, but to little avail. Rejections didn’t bother him. The reason to overcome the fear of rejection was his formative upbringing, and stint at the boarding school. From being rejected by seniors to becoming a part of the group, to being denied extra pocket money, to being not able to clear the IIT entrance… Dubey had a long innings of ‘nays’ in his life. Meanwhile, after his telemedicine venture didn’t get the green light, two years later, he co-founded CarWale, an automotive classified portal in 2005.

The idea was to connect distant villages with district hospitals. The problem, though, was that few believed in his idea. For three years, Dubey made futile attempts to convince government officials and politicians, but to little avail. Rejections didn’t bother him. The reason to overcome the fear of rejection was his formative upbringing, and stint at the boarding school. From being rejected by seniors to becoming a part of the group, to being denied extra pocket money, to being not able to clear the IIT entrance… Dubey had a long innings of ‘nays’ in his life. Meanwhile, after his telemedicine venture didn’t get the green light, two years later, he co-founded CarWale, an automotive classified portal in 2005.Also read: Shailesh Kumar's shoe-string upbringing and the curious case of CABT Logistics

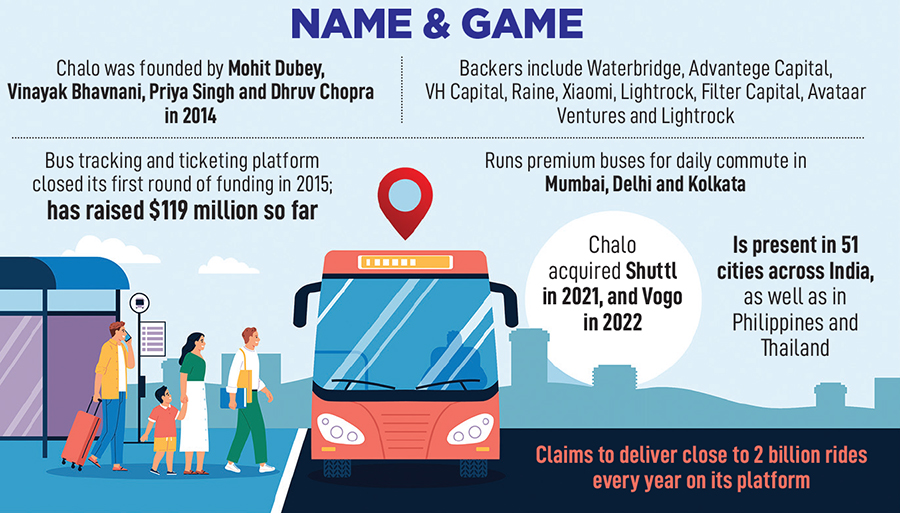

Cut to 2020. Dubey was into his sixth year of his second entrepreneurial gig. And this time, the entrepreneur listened to his heart and co-founded intra-city bus tracking and ticketing platform Chalo in 2014. Six years later, Covid disrupted the travel and hospitality sectors, and many founders like Dubey. Revenues vanished, investors panicked, and Chalo was left stranded. Over the next few quarters, as the pandemic eased a bit and travel came back on track, Dubey tried knocking on the doors of over three dozen funders. “Nobody was interested. All rejected,” he says.

Back in 2014, ‘rejection’ haunted the entrepreneur who was taking a bold step. By 2013, Dubey realised that cars were not the best vehicles to reach out to the masses. Car penetration, which was one car for 100 Indians in 2008, had laboured to two cars per 100 Indians in five years. A reason for the muted growth in car ownership in cities was largely due to the mushrooming services of Ola and Uber which had made city slickers stay away from buying cars. “Indian mobility is definitely not cars,” he concluded. Buses had the wheels that moved Bharat. In terms of business too, buses made sense. The sector was six times bigger than the taxi segment, and presented a $20-billion opportunity.

There was another reason to board the bus. Dubey was influenced by Peter Thiel. The German-American billionaire entrepreneur and venture capitalist once talked about two kinds of businesses: One with competition, and one without. Dubey yearned for two things: A business without competition, and a venture which touched the lives of millions in smaller cities, towns and villages. Chalo ticked all the boxes, and Dubey decided to shift gears from cars to buses. Friends, colleagues, experts and industry observers found the idea outrageous. “Can buses make money?” was the big question.

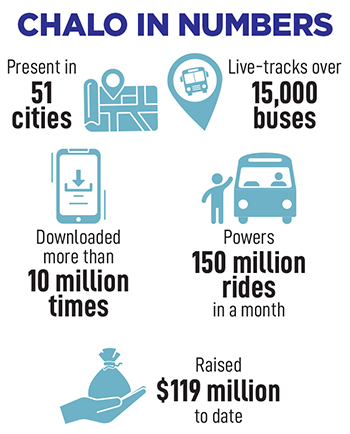

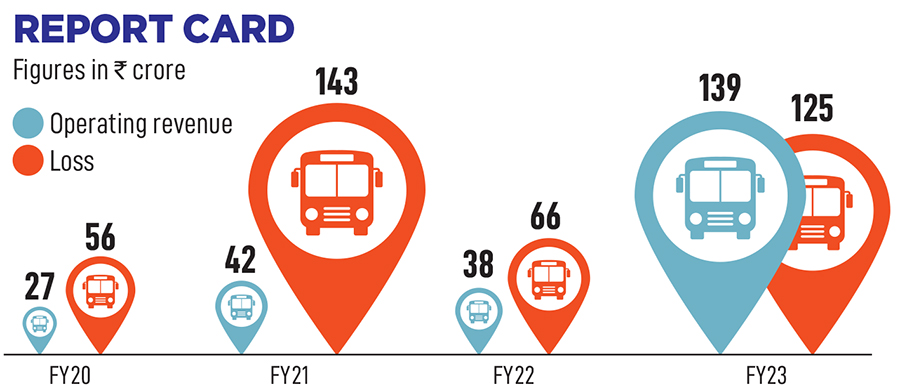

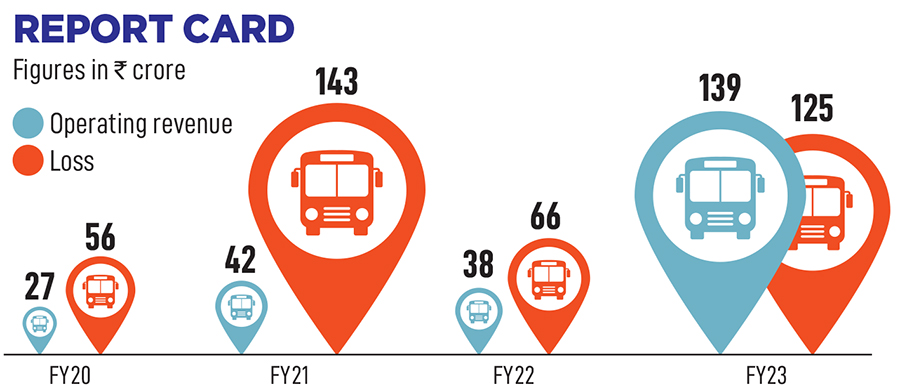

Nine years into the bus ride, Dubey has the answer. Chalo increased its operating revenue from ₹27 crore to ₹139 crore in FY23. A big factor aiding a jump was a slew of acquisitions over the last few years: Shuttl in 2021, and Vogo in 2022. Overall, Chalo has raised $119 million so far from a clutch of backers such as Waterbridge, Advantege Capital, VH Capital, Raine, Xiaomi, Lightrock, Filter Capital, Avataar Ventures and Lightrock. The startup is present across 51 cities and towns, as well as has an overseas presence in Philippines and Thailand. “We deliver close to 2 billion rides every year on our platform,” claims Dubey.

Industry observers are not surprised with the diverse trajectory of Dubey: From cars to buses. “Most of the founders from small towns solve real-world problems that are closer to the environment,” says Anisha Singh, founder of She Capital. “They are not only more optimistic but also more resourceful.”

Dubey, meanwhile, shares his best resource: Learnings from small towns. “It made me fearless. I don’t fear failure and rejection,” he says, adding that he keeps himself balanced by staying rooted to his background. The upbringing, he underlines, also had an impact on the way the entrepreneur builds his team. “I don’t look for degrees and pedigree. I look for hustlers and people who can adapt,” he says. Small town, Dubey reckons, gives you wings. “But only the ones with immense self-belief can discover them,” he says. The founder, it seems, has loads of them.

(This story appears in the 15 December, 2023 issue of Forbes India. To visit our Archives, click here.)

Post Your Comment