Tushar Mittal: Journey from an enterprising boy to an insatiable entrepreneur

A village boy from Rajasthan fights formidable odds and manages to turn the tables on adversity with his bootstrapped venture Studiokon Ventures (SKV). Can Tushar Mittal now get a seat at the table with his VC-backed Officebanao?

Tushar Mittal, founder and CEO of Officebanao

Image: Amit Verma

Tushar Mittal, founder and CEO of Officebanao

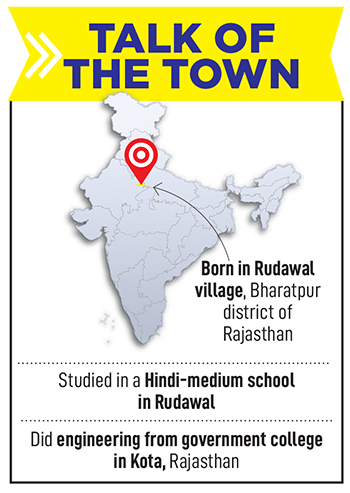

Image: Amit Verma Rudawal, Bharatpur, Rajasthan. The ‘agonising’ Friday was back to haunt the village boy. It was a day when Tushar Mittal found himself helpless, and emotionally torn between his moral duty and dream. On one side was his industrious father who ran a small kirana store in a remote village, and on the other hand was the burning desire of the 12-year-old to be in school every day. “Aaj dukaan pe baith jaa [take care of the shop today],” was the command from the second-generation shop owner who used to go to Jaipur—the capital city of Rajasthan was some 200 km from Rudawal village in Bharatpur district—once in 30 days to buy his monthly quota of ration. “He wanted me to take care of the store on the last Friday of every month,” recalls Mittal. “Kuch seekhega nahin school jaake [you will learn nothing at school],” was the assessment of the man whose kirana store was the only shop in the village.

A young Mittal gave in to his duty, and unpacked his bag. Though he was aware of the monthly ritual—and also the fact that there was some element of truth in what his father uttered about the quality of education in the school—he eagerly looked forward to his daily learning. The fact that he had to walk a few kilometres every day to attend the government school was never a deterrent. The fact that most of the time the teachers used to bunk their classes never dampened the enthusiasm of the young learner. And the fact that even English used to be taught in Hindi was not a bummer for Mittal. “My uncle always used to tell me that I can change my destiny through studies,” recalls Mittal, who ran away from his home after finishing senior secondary. Reason: He wanted to study.

A little help from his relatives landed him at a coaching institute in Kota. The father relented, took an education loan from a PSU bank, and the rebel boy started preparing for the engineering entrance. He failed in his first attempt to clear IIT, and lack of financial resources preempted any move to continue with his studies for another year. “I got admission in a government engineering college in Kota,” says Mittal, who opted for civil engineering. To make ends meet, he started working with local contractors on a part-time basis and also ran a canteen in Kota. This was, however, not the first time that the young boy was exhibiting his enterprising side. During his school days, he used to borrow money from his father, buy comics from the nearest town, and then rent them to his friends. “I even bought a cycle, and gave it to my friends on rent,” he recounts.

A little help from his relatives landed him at a coaching institute in Kota. The father relented, took an education loan from a PSU bank, and the rebel boy started preparing for the engineering entrance. He failed in his first attempt to clear IIT, and lack of financial resources preempted any move to continue with his studies for another year. “I got admission in a government engineering college in Kota,” says Mittal, who opted for civil engineering. To make ends meet, he started working with local contractors on a part-time basis and also ran a canteen in Kota. This was, however, not the first time that the young boy was exhibiting his enterprising side. During his school days, he used to borrow money from his father, buy comics from the nearest town, and then rent them to his friends. “I even bought a cycle, and gave it to my friends on rent,” he recounts.

A few years later, in 2005, Mittal didn’t have any money to pay rent when he landed in Delhi. After finishing engineering, he wanted to join National Institute of Construction Management and Research (NICMAR).

The trigger was his three-month internship at a big, multinational construction company during his college stint. Mittal noticed that the engineers who were armed with a degree from NICMAR had an edge over others in salaries as well as professional stature. He borrowed money from his friends and relatives, came to Delhi and stayed at Nizamuddin Railway station for a few days.

The trigger was his three-month internship at a big, multinational construction company during his college stint. Mittal noticed that the engineers who were armed with a degree from NICMAR had an edge over others in salaries as well as professional stature. He borrowed money from his friends and relatives, came to Delhi and stayed at Nizamuddin Railway station for a few days.

After the professional course, Mittal discovered another bitter reality. Though a campus placement landed him a job at DLF, he didn’t stand a chance among his peers who came from hallowed institutions, had a privileged background and flaunted their fluency in English. “They got laptops and desk jobs, and I was made to run in the fields,” rues the civil engineer who struggled with his communication skills. “I thought that the language barrier in the city will never let a village boy shine,” he says. “I felt dejected.”

The curse, though, turned out to be a blessing in disguise. The field job helped Mittal get his hands dirty, learn the tricks of the construction business, and build trust with vendors, contractors and other stakeholders in the industry. There was another plus. The young professional used to work late to ensure that he had an edge over his colleagues. The office used to get vacant by 7 pm, but Mittal’s day ended after midnight.

He had two more reasons to spend more time in office. The first was to literally keep his cool. “I didn’t have an air-conditioner [AC] in my one-room flat,” he says. “Working late in office meant spending some time in AC,” he smiles. The second was to fend off the pressure from his family and a bunch of lenders. A ₹17,000 monthly salary was not something that his father expected from his lad who defied him and refused to take care of the kirana store. “Itney toh mere se hi le leta [you could have easily taken this amount from me] was the recurrent cold jibe from his dad. Mittal was also juggling to manage the bank loan and money borrowed from a clutch of friends and relatives to continue his education. All had exhibited exemplary patience. But Mittal’s job at a big brand like DLF gave them a false impression about the ‘handsome’ salary package. “They all wanted their money as soon as possible,” he says.

He had two more reasons to spend more time in office. The first was to literally keep his cool. “I didn’t have an air-conditioner [AC] in my one-room flat,” he says. “Working late in office meant spending some time in AC,” he smiles. The second was to fend off the pressure from his family and a bunch of lenders. A ₹17,000 monthly salary was not something that his father expected from his lad who defied him and refused to take care of the kirana store. “Itney toh mere se hi le leta [you could have easily taken this amount from me] was the recurrent cold jibe from his dad. Mittal was also juggling to manage the bank loan and money borrowed from a clutch of friends and relatives to continue his education. All had exhibited exemplary patience. But Mittal’s job at a big brand like DLF gave them a false impression about the ‘handsome’ salary package. “They all wanted their money as soon as possible,” he says.

Hard work brought in its wake some unforeseen opportunities. One of the project managers made an untimely exit, a large contract got stuck, and consequently the project got delayed. Mittal was picked up as the Man Friday and asked to prove himself. And he proved his mettle in a remarkable way by delivering the project in two weeks. Soon, the unofficial crisis man was in huge demand.

Meanwhile, Mittal was busy calculating ‘demand and supply’ of a different kind. A little over one-and-a-half years into the job, Mittal resigned. He spotted something that the others couldn’t.

Meanwhile, Mittal was busy calculating ‘demand and supply’ of a different kind. A little over one-and-a-half years into the job, Mittal resigned. He spotted something that the others couldn’t.

“That something was a huge demand, poor supply and a big opportunity,” he says, alluding to the dynamics of the office construction industry in 2008. The segment was overwhelmingly unorganised, there was a stark absence of professionals and the demand for office interiors in top cities as well as tier 1 towns was picking up at a furious pace. Mittal decided to take the plunge into entrepreneurship.

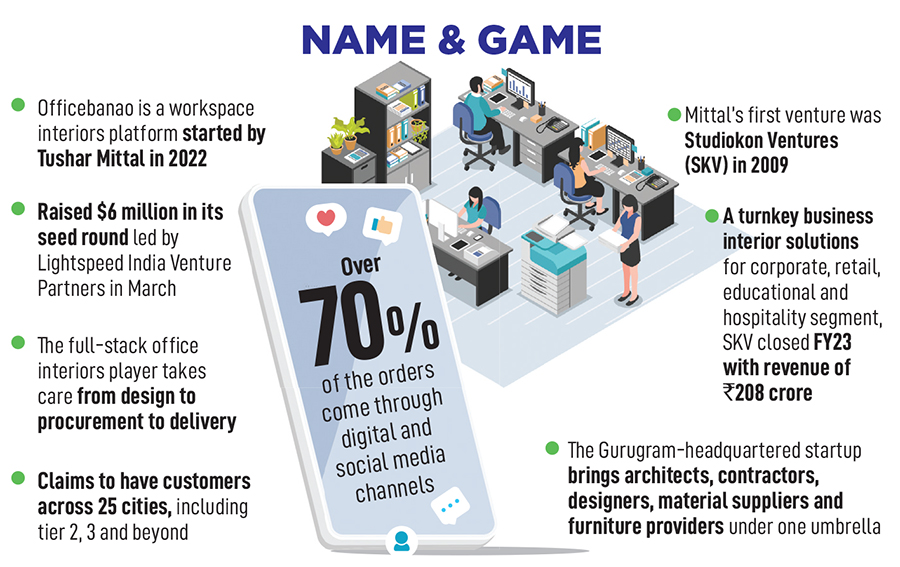

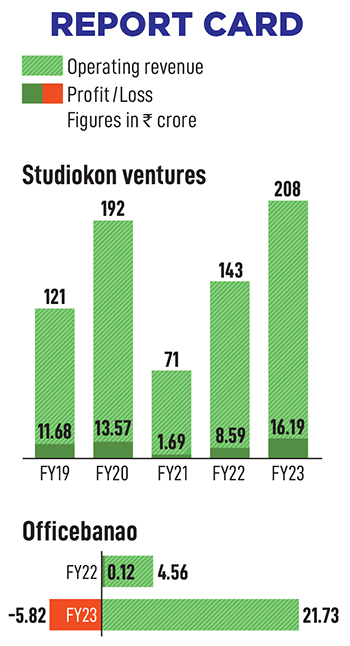

It proved to be disastrous though. Mittal stitched two failed partnerships in over a dozen months. The sad part was not the failure, but the breach of trust. Conned by his partners, and shaken by the bitter experience, Mittal went solo in 2009 and rolled out Studiokon Ventures (SKV). A bootstrapped firm, SKV provided turnkey business interior solutions to corporates, retailers, and educational and hospitality institutions. The business had a promising start and Mittal earned ₹10 crore in the first year. Over the next few quarters, SKV gathered steam and kept expanding at a furious pace. By 2015, the bootstrapped company was close to the ₹100-crore mark and remained profitable.

Then came the turning point. For years, Mittal lived with an unwarranted guilt of not having education from a world-class institution. The opportunity came in 2016 when he got to know about the executive education programme of Harvard.

He enrolled himself, immersed himself in the course, and was set to face an unintended fallout in India. The business, which was in an auto pilot and growth mode, kept bagging big projects, especially from a battery of MNC players. This called for hefty investments and meeting a flurry of tight financial deadlines and protocols.

SKV slipped on most counts, and the business suddenly faced a working capital deficit of ₹80 crore. To salvage the situation, Mittal disposed of an office in Gurugram, and his wife Swati sold all her jewellery and dipped into her life savings.

“She played a big part in saving the business,” says Mittal. The business came back on track in 2017, clocked a revenue of ₹121 crore in FY19 and was on track to breach the ₹200-crore mark.

Then came another twist. Armed with his Harvard learnings, and the teachings of his professors, Mittal decided to amp up his entrepreneurial game by several notches. The trigger, he explains, was the motivational push by one of the professors at Harvard.

Then came another twist. Armed with his Harvard learnings, and the teachings of his professors, Mittal decided to amp up his entrepreneurial game by several notches. The trigger, he explains, was the motivational push by one of the professors at Harvard.

“Anybody can make money, but a founder has to build a brand and leave a legacy,” his mentor drilled the point into his disciple’s mind. The teacher made Mittal face some searing questions: Do you see a similar trajectory for SKV? Can you build it into a ₹10,000-crore company? Can your name be synonymous with trust in the construction business? Once back in India, Mittal decided to launch Happy Monday towards the latter half of 2019. A managed office space venture which offered flexible workspaces to global and Indian corporates, Happy Monday had a brisk start.

Within months, though, Happy Monday had an unhappy ending. The pandemic came calling in March 2020, offices shut down, and Mittal was forced to pull the plug on the venture.

The next 12 months tormented the entrepreneur who struggled to stop the slide in the main business of SKV. The revenues dipped from ₹192 crore in FY20 to ₹71 crore in FY21. Profit too slipped from ₹13.57 crore to ₹1.69 crore during the same period.

Things were uncertain, the future looked gloomy, and the entrepreneur was hunting for an elusive light at the end of the long tunnel. Unfortunately, it was pitch dark.

Years ago in Rudawal, a young boy was struggling to finish his school work. For many hours a day, the village usually remained pitch dark. “The electricity supply was erratic,” recalls Mittal, who tells us that something else was gloomy on another front.

The kirana business mostly happened on credit, it was normal for the payment cycle to get delayed, and his father grappled to keep operations and the venture intact. There was a devastating fire one year. The house and the shop got gutted. His father had to start from scratch.

Also read: How Sibabrata Das and Atomberg's smart appliances are standing up to goliaths

Also read: How Sibabrata Das and Atomberg's smart appliances are standing up to goliaths

“He worked hard and never complained,” recalls Mittal. Cribbing, his father used to underscore, makes one lazy and takes one’s eyes off the problem. “You must face it, not evade it,” was his advice to his son.

Back in 2020, Mittal was bravely staring at the problem. He cut his expenses, curtailed the expansion plans, and waited for the bitter macro and micro environment to settle down. And things did start to normalise. The revenues bounced back from a low of ₹71 crore to a high of ₹143 crore in FY22. The same year, Mittal decided to revisit his grand plans of building a brand and creating a legacy, which he couldn’t with Happy Monday. He started Officebanao, a workspace interiors platform that takes care from design to procurement to delivery.

Officebanao has a unique playbook. The Gurugram-headquartered startup brings architects, contractors, designers, material suppliers and furniture providers under one umbrella. In March, it raised a funding of $6 million in seed round which was led by Lightspeed India Venture Partners, and over the next few months it expanded its play across 25 cities, including tier 2, 3 and beyond. “SKV reinforced my self-belief that a village boy can do anything,” says Mittal. “Officebanao will use the tech template to build a brand and take it across the country.”

Founders from the hinterland, reckon industry observers, have led a strapped life in terms of resources. “You give them an inch, and they will convert it into a metre,” contends Sushil Sharma, founder of Marwari Catalysts, a Jodhpur-based startup accelerator that has been backing founders from small towns over the last few years. “Their hunger to succeed is insatiable because they have nothing to lose. All they want to do is to prove themselves,” he says.

Mittal, for his part, just wants to prove one thing. “When life gives you lemons, make lemonade. This is what I have been doing,” he signs off.

(This story appears in the 15 December, 2023 issue of Forbes India. To visit our Archives, click here.)

Post Your Comment