Donations to religious organisations in India runs into crores. But how transparent is the management?

From Rs 10-20 to gold and silver jewellery, copper, donations to temples and other religious organisations in India amounts to crores of rupees but there is no clear account of how it is being utilised

Donations to places of worship and religious institutions can amount to several thousand crores in India, often overshadowing the wealth of business conglomerates

Image: Shutterstock

Donations to places of worship and religious institutions can amount to several thousand crores in India, often overshadowing the wealth of business conglomerates

Image: ShutterstockWalking through the narrow and crowded lanes of Varanasi in Uttar Pradesh (UP), the chiming of temple bells and chants of ‘Har har mahadev’ are constants. Proclaimed by Unesco as one of the oldest living cities in the world, Varanasi, also known as Benaras and Kashi, is known for its 84 ghats and more than 3,000 temples; Unesco has also chosen it as a city of music. Walking past a wedding and a funeral procession, within 15 minutes of each other, is quite usual here. After all, one of the holiest cremation grounds and one of the most important places of worship—Manikarnika Ghat and Kashi Vishwanath temple, respectively—are situated right next to each other.

Most devotees inside the temple donate ₹10-20, or more, in the donation box, with many believing their prayers will come true; some others think it will be used to help someone. Philanthropy is rooted in India’s history and culture, with traditions such as daan, seva, zakat, tithe and langar cutting across religions and regions. Everyday donors might not have large resources at their disposal, but they still contribute in small ways.

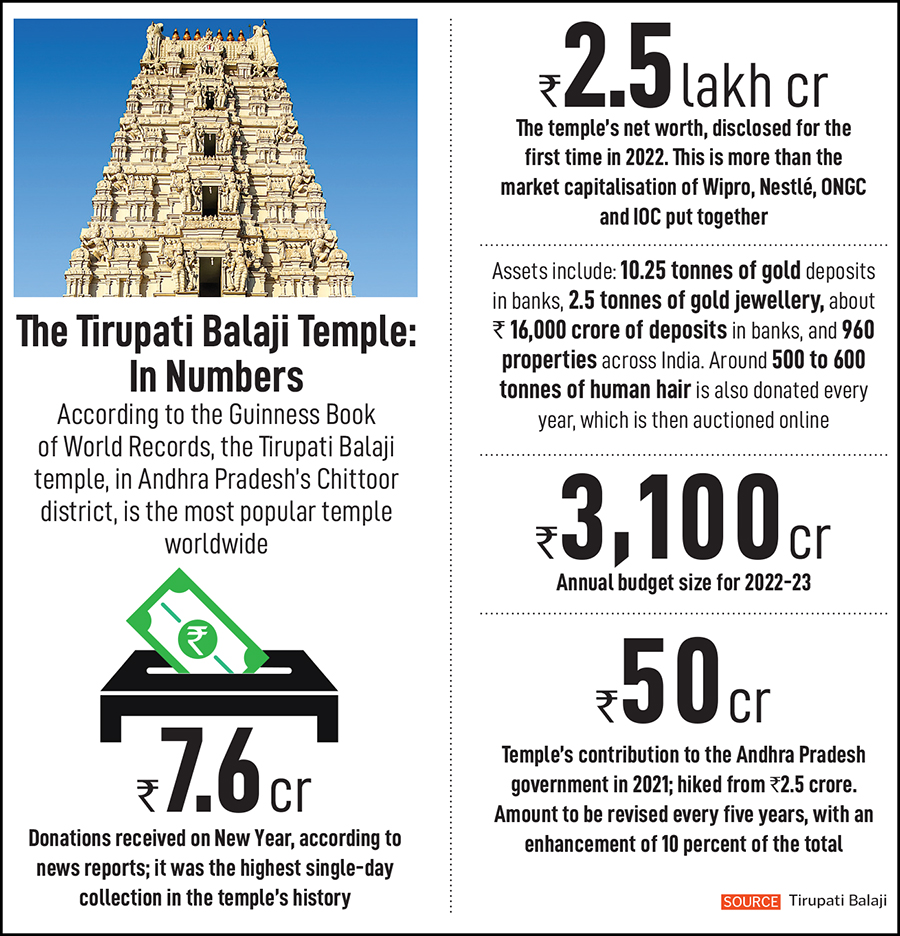

Donations to places of worship and religious institutions—daily amounts, however small, dropped into collection boxes, and big-ticket offerings such as jewellery made of gold and silver—can amount to several thousand crores in India, often overshadowing the wealth of business conglomerates. Although most donations are made in good faith, transparency remains a concern.

In 2022, donations made to the Kashi Vishwanath temple increased fivefold, to more than ₹100 crore, and footfalls increased 12 times, to 7.35 crore, over the previous year, said Sunil Kumar Verma, CEO of Kashi Vishwanath Dham, in an earlier media report. Apart from cash, devotees donated 60 kg gold, 10 kg silver and 1,500 kg copper; around ₹50 crore was donated in cash, of which 40 percent was donated online. Ever since the Kashi Vishwanath Corridor—a pathway connecting the temple to the bank of the Ganga—was inaugurated in December 2021, the temple has seen a surge in donations, added Verma. Since 1983, all donations are collected by the UP government.

OP Shukla, an auditor of the Kashi Vishwanath Temple Trust who has been handling the temple’s accounts for 23 years, says donations are used for the maintenance and development of the temple and to feed over 500 destitutes every day. “Over the years, the inflow of donations has only increased. The UP government has appointed five trustees and one chair on the board, to run the temple. A minimum of ₹2 crore is collected from the donation box every month,” he says.

However, Kulpati Tiwari, 72, a former chief priest of the temple, who served for over three decades says since the government took charge of the temples, priests have stopped getting paid. “There is no proper calculation of where the money is being used. Universities, schools, orphanages and health care facilities should be opened using this money,” says Tiwari, who claims to have written to the prime minister and president regarding the issue, but has not received any response. He believes the money from donations should ideally be used for priests and the betterment of society, but the government doesn’t bother to address these problems, and instead it has all become a business run by politicians.

Also read: Radhika Bharat Ram: Empowering girls with education, agency

Given to God, but in human hands

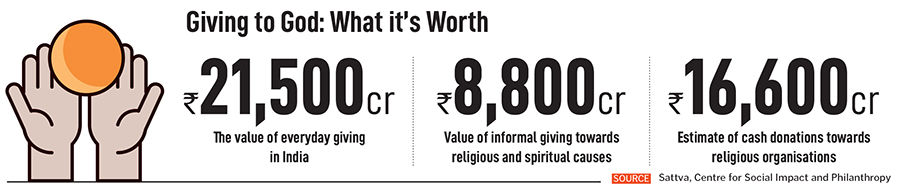

According to a 2019 report by Sattva Consulting, a social impact consulting firm, everyday giving—ways in which people give their time and money—in India is valued at about ₹21,500 crore, and giving towards religious and spiritual causes is worth ₹8,800 crore. A 2020-21 report by the Centre for Social Impact and Philanthropy (CSIP) at Ashoka University says religious organisations (cash donations of ₹16,600 crore, constituting 70 percent) and beggars (₹2,900 crore, constituting 12 percent) are the most preferred recipients of household giving. Family and friends constitute 9 percent (₹2,000 crore), non-religious organisations 5 percent (₹1,100 crore), and household staff 4 percent (₹1,000 crore). Among households, 64 percent contribute to religious organisations, with the most common motivation being family traditions that encourage giving on special or auspicious occasions.For certain families in India, especially the middle-class, giving to religious organisations is a priority because we are a deeply religious society, says Neera Nundy, co-founder of philanthropy foundation Dasra.

The net worth of Tirupati Balaji temple (left), disclosed for the first time in 2022, was ₹2.5 lakh crore

Image: Arun HC/ UIG via Getty Images

The net worth of Tirupati Balaji temple (left), disclosed for the first time in 2022, was ₹2.5 lakh crore

Image: Arun HC/ UIG via Getty ImagesShe adds that there are different outcomes of being a religious society. One outcome is that it comes from a deep set of values that can be very strong, as it helps build a good society. Another outcome is that in some religions, there is a mandate or expectation of giving back to the community or the religion in some form. For instance, religions such as Sikhism, Islam and Christianity encourage giving 10 percent of one’s annual income away as daswandh, zakat or tithe, respectively.

“If so much charity is made in the name of religion, there needs to be a way to build more accountability, because people are giving with a deep faith in God. There is a lot of trust built into religious institutions. And maybe it’s not our part to ask, but ultimately, it’s in the hands of humans. So, it’s like human to humans. We should be holding each other accountable. Is this money ultimately addressing the injustices that occur? I think closing the loop is something we need to work on so that it doesn’t take away from the faith to ask for transparency and accountability,” says Nundy.

In September, Malini Bhattacharjee, an associate professor at Azim Premji University, conducted a qualitative study on ‘Sacralising the Secular: Philanthropy in Christian, Hindu and Islamic Organisations’. She tells Forbes India the religious organisations she spoke to are very adaptive. “The dichotomy that we have in our minds is that there are a set of secular organisations and there are a set of religious organisations. This dichotomy is diluted to an extent that religious organisations are as much into transparency, bookkeeping, maintaining records and providing receipts for subscriptions as secular organisations. They’re very professional, their bureaucracy and their bookkeeping are completely up to speed,” she says.

Most of the respondents that Bhattacharjee interviewed believed that the work their organisations did were free of any agenda and did not discriminate amongst the beneficiaries.

“They also believe that their work is superior to that of secular organisations, because it comes from a place of spirituality, trying to purify one’s soul, and earning good karma. They believe it is their USP that helps them project themselves as more legitimate and prominent partners in philanthropy.”

The manner in which religious organisations are managed is different for different religions. According to a public interest litigation (PIL) filed by BJP spokesperson Ashwini Upadhyay in the Supreme Court, state governments control the management, income and assets of many temples and gurdwaras. However, mosques and churches in India have no such government controls. The PIL pressed for the right of Hindus to manage their religious places without government interferences, like Christians and Muslims.

Most devotees donate to religious places hoping that their prayers will come true and that the money will be used to help the needy

Image: Shutterstock

Most devotees donate to religious places hoping that their prayers will come true and that the money will be used to help the needy

Image: ShutterstockIn response, the Supreme Court, last September said, “Since all temples’ earnings are from people, they may well go back to them by way of setting up colleges and universities.” The court raised doubts over the necessity of revisiting the 1863 Religious Endowments Act, which facilitated temples to cater to the “larger needs of the society”.

“The PIL seems like a precursor to bringing about a Uniform Civil Code which is debatable. So far, as Article 14 is concerned, the Religious Endowments Act, 1863, is per se not violative of it, as Hindus form a class of persons. And, constitutionally, there’s no bar on the state to make similar laws for other religions,” says Nandita Surollia, an advocate at the Gujarat High Court, adding that minority religions like Christianity and Islam are run by the heads of religious organisations, while there is a law for Hindu endowments. She says that, to create parity, all religious organisations should be governed by the same law for proper checks and balances. “I feel some reasonable regulation must be made over all religious places in India to curb misuse of funds and bring about parity,” Surollia tells Forbes India.

The generation gap

Ruchi Jain, 47, is a social worker who has formed a community of people who help underprivileged children, take care of their education, deliver ration to deprived families, look after cows, and build and take care of Jain temples. She, along with other community members, have built eight Jain temples in Pune. “I am not doing this for anyone else; I am doing this charity for myself and collecting good karma. We Jains believe in karma, because at the end of this life all we are going to take with us are our good deeds. I pass on the same values to my children and I ensure they celebrate their wins or any auspicious day by first donating somewhere and partying later,” says Jain, who spends around ₹12-15 lakh every year towards religious and other philanthropy.

This sentiment, however, is not universal among younger generations. For instance, Nimisha Zaveri, 37, who is co-founder of Ahmedabad-based jewellery store Papilior and mother of two children, says she has grown up in an environment where she saw her grandparents and parents donating money to religious organisations. The concept has never resonated with her and hence she decided to donate in other ways—such as funding the education of needy children. She intends to imbibe the same values in her children.

Yash Vidhani, 27, a senior manager with Urban Company, says growing up in a Hindu society, he has seen his parents being spiritual and worship different Gods at different phases in their lives, and over time, their learnings developed on the concept of spirituality. Now his parents support an NGO that is into spiritual causes and giving back to society. “Personally, I don’t believe in idol worship. Till 18, I was confused about the existence of God, but today I believe this universe is governed by some sort of energy and in order to feel that energy, I have been doing vipassana.”

Others that Forbes India spoke to reflect this shift in beliefs. While some will happily continue the legacy of donating to religious organisations, others said they would do it only to make their parents happy, but will not pass it on to the next generation. Some more said they would rather switch to giving back to society and see the outcome in front of themselves, like donating to NGOs.

Nundy of Darsa explains, “If the elders ask young people to give to religion, it will continue; it may come from the values side of things, which is important. But the amazing part is, young people don’t have a problem, especially millennials, in asking for accountability. I think we could leverage young people to have those uncomfortable conversations.”

(This story appears in the 10 March, 2023 issue of Forbes India. To visit our Archives, click here.)

Post Your Comment