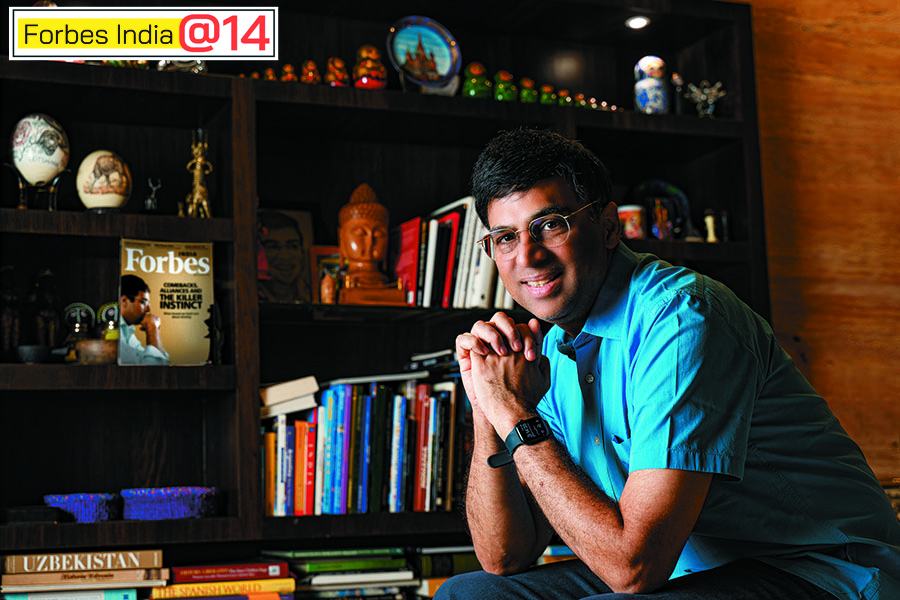

Indians no longer want to just play chess; they want to be the best: Viswanathan Anand

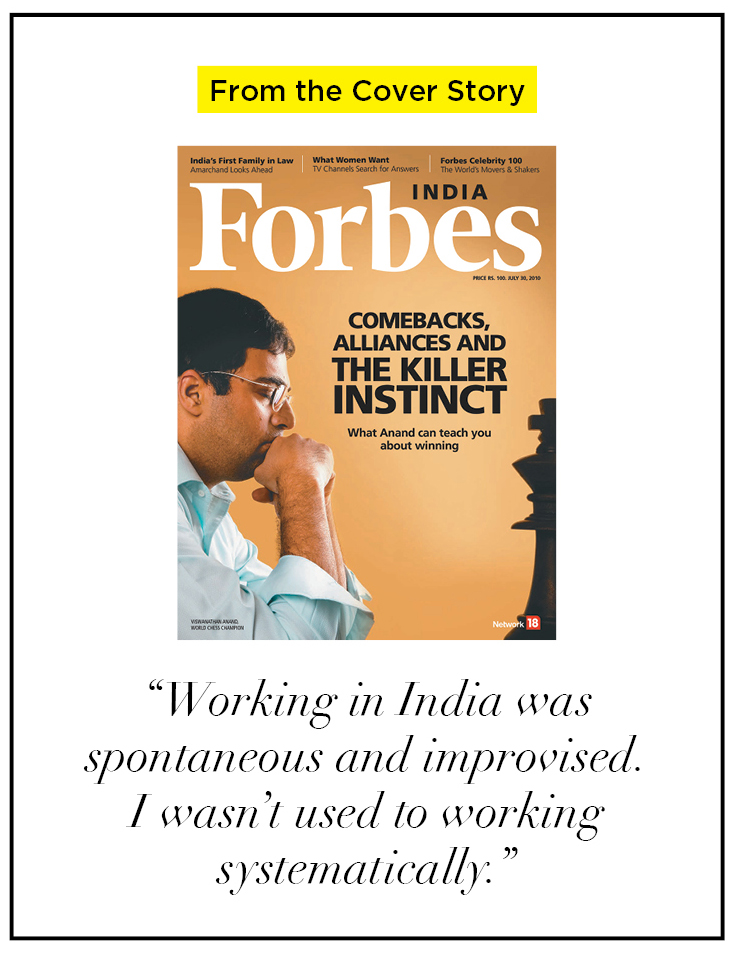

Viswanathan Anand, India's first Grandmaster and our cover personality in 2010, has bounced back from setbacks and mastered the art of winning. The five-time World Champion, who is now at the forefront of mentoring the next generation to the top, reflects on how India has come to be recognised as a global chess powerhouse

India’s first Grandmaster, Viswanathan Anand

India’s first Grandmaster, Viswanathan Anand

Before I became India’s first Grandmaster (GM), the biggest barrier was probably mental. No one had become a GM and it had a climb Everest kind of feel to it.

In those days, it was much harder to be a GM, since you had to compete against other GMs to become a GM. And the world supply of GMs back then was far more limited. One had to organise special tournaments to play GMs, and those had a far stronger playing field than today. So, we had to take every chance we got.

My big break came in 1987 when I won the world junior championship, the first Asian to do it. And the next year I became a GM. Once that happened, the possibilities really opened up for me to take up chess as a serious career. The tournament organisers would look after my expenses and I would also get invitations to play at very good tournaments like the Tata Steel event in The Netherlands.

Around mid-1990, I qualified for the Candidates, the contest which decides the challenger for FIDE’s elite world championships. That was the ultimate breakthrough because, from then on, I started going to the absolute best tournaments. So you might consider the GM as the stepping stone to this world.

Also read: Electronics manufacturing sector needs to be self-reliant and invest heavily in R&D: Sunil Vachani

I was fortunate to become a GM at a time when training wasn’t absolutely essential to becoming one. Computers didn’t exist back then. In 1987, after I won the World Junior, I saw the first database programme had appeared. And I got my first computer only after a couple of months after becoming the GM. Nowadays, training, coaching methods tilt the field a lot and you’re unlikely to become a GM unless you are able to invest in these things.

But I didn’t think the lack of infrastructure or the awareness about chess were handicaps for me because I was getting stronger by playing against better players. It forced me to keep making the tweaks necessary to improve. And it helped me put off formal coaching till very late—after the Candidates—because improvising made you resilient.

What also changed along the way was the attitude of other GMs. I met Anatoly Karpov in 1988, and he spoke to me like a colleague. Same with Garry Kasparov, with whom I even shared a manager. The world of chess accepted me and it was game-changing.

Within India, the real impact was felt in the chess ecosystem as it got a lot of people, especially the group just behind me that comprised the likes of Dibyendu Barua, Pravin Thipsay etc, excited at the possibility of becoming a GM. Barua became India’s second GM just three years later.

But even in 2000, we were only at six GMs. It was a slow climb, but a climb alright as we started to hear anecdotal stories about how even school tournaments were running out of chess sets and clocks. These were the very first signs of a chess wave. But even then, the world didn’t recognise India as a rising power in chess. That came in the last 10-15 years where the organisers of a number of open tournaments in Europe suddenly realised that one-tenth of the participants were from India.

A few years ago, I launched the Westbridge Anand Chess Academy, starting with players who had become GMs under the age of 14. And there were already five of them. No wonder we already have 82 GMs.

I suspect that absolute acceptance of India’s prowess in chess came in the last 10 years, where more and more Indian youngsters were present in tournaments. And as these kids started to play top players and defeat them, especially in the last five to six years, people started to acknowledge India as a powerhouse. Even Magnus Carlsen, the world champion who has thrice been defeated by teenager R Praggnanandhaa, has said the next World Champion could probably be from India. Before, such statements would refer to me, now it refers to one of the others.

I suspect that absolute acceptance of India’s prowess in chess came in the last 10 years, where more and more Indian youngsters were present in tournaments. And as these kids started to play top players and defeat them, especially in the last five to six years, people started to acknowledge India as a powerhouse. Even Magnus Carlsen, the world champion who has thrice been defeated by teenager R Praggnanandhaa, has said the next World Champion could probably be from India. Before, such statements would refer to me, now it refers to one of the others. In India, one wave has facilitated the next. The first generation of youngsters, who took to the game right after me, typically joined public sector companies, banks—that was valuable support because it meant financially they were stable. A lot of them went on to start coaching centres and, slowly, activities for those who wanted to play chess started increasing. Through these, the earlier generation was also able to pass on its expertise to the next.

So, when I started the academy with Westbridge Capital, the idea wasn’t just to get Indians to play chess, but to see how we can get Indians to the very top. Because, by now, only that is aspirational. We’ve set our sights higher because once you have a World Champion, you can’t get too excited about achievements below that level.

When I hit the top 10, I suddenly realised I needed to work with the best trainers. At that point, it could only be done in personal sessions. So I travelled to Europe often, I started living there partly since I needed a base in Europe. Indian players don’t have to do this anymore. Travel has become easier, they’ve developed friendships across distances, and coaching methods in India have risen to a point where they can be called world-class. Now we have kids from other countries learning from Indian coaches.

When do we hit 100 GMs? It could happen very fast. We were rooting for 75 during the Olympiad in July-August to time it with the 75th anniversary of Independence, and we are already at 81. So, it might just go very fast. Maybe in the next year and a half?

(As told to Kathakali Chanda)

(This story appears in the 16 June, 2023 issue of Forbes India. To visit our Archives, click here.)

Post Your Comment