Satyanarayan Nuwal: From sleeping on railway platforms to building the Rs 35,800 crore Solar Industries

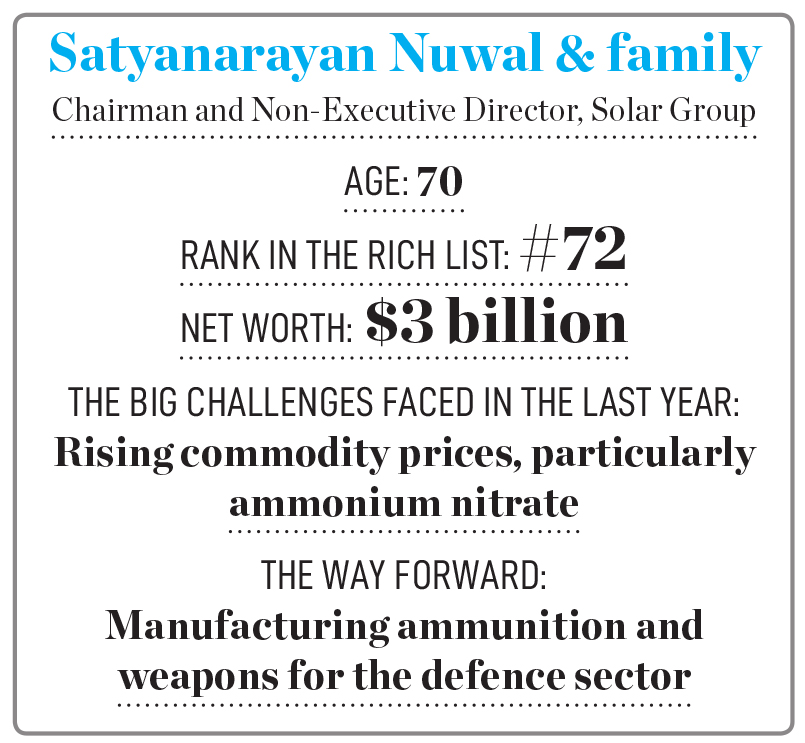

Nuwal has made Solar Industries into a leading industrial and ammunition manufacturer. At 70, he debuts on the list of India's 100 richest, and he is looking to take giant strides in defence manufacturing

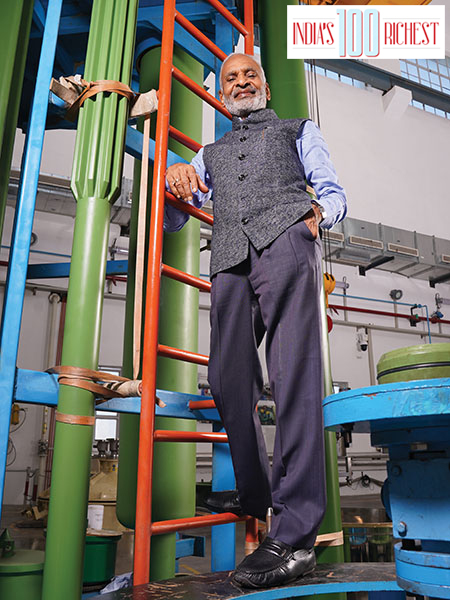

Satyanarayan Nuwal, Chairman, Solar Industries

Image: Mexy Xavier

Satyanarayan Nuwal, Chairman, Solar Industries

Image: Mexy Xavier

Satyanarayan Nuwal generally prefers speaking in Hindi. English was never his first or second language, and Nuwal had dropped out of school after class 10. However, when the reclusive billionaire decided to sit down for an interview with Forbes India, self-admittedly a little worried about the conversation, he was certain about one thing—he was going to speak in English, a language, he admits, he doesn’t know very well. He even lined up a few of his officials in case he found it difficult to put across his views. That perhaps speaks volumes about the grit and tenacity of the 70-year-old who has made it a habit of taking on challenges and never giving up without a fight.

Nuwal is chairman of the ₹35,800-crore (market capitalisation) Solar Industries, a Nagpur-headquartered industrial explosives and ammunition manufacturer, that he founded in 1995. The company has a presence across 65 countries and is the largest manufacturer of industrial explosives and explosive initiating systems in India today.

Solar Industries began as a supplier of explosives to state-owned coal mines and as a consignment agent for the chemical company ICI (Imperial Chemical Industries) before deciding to foray into manufacturing its own explosives by the turn of the millennium. Then, a little over a decade ago, it decided to foray into India’s lucrative defence sector, which has now been given a massive impetus by the government’s Make in India initiative. Currently, Solar Industries makes everything from explosives and propellants to grenades, drones and warheads, among others.

The company has also developed India’s first-of-its-kind weaponised drones and loitering munitions (suicide drones) that it intends to provide for the Indian armed forces. “It is my passion to build up our defence business,” says Nuwal. “It is also our moral responsibility to the country. For any country, if you are not strong in security or defence, it is very difficult to sustain.”

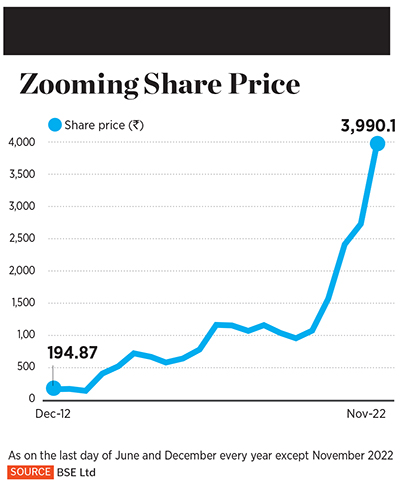

That foray into defence, along with its dominant market share in the industrial explosives market, has meant that the company’s market capitalisation has grown by some 1,700 percent in a decade—from ₹1,765 crore in 2012 to over ₹35,000 crore as of November 2022. In the process, Nuwal, whose family holds a 73 percent stake in the company, has seen his wealth swell to $3 billion, making him India’s 72nd richest person on the 2022 Forbes India Rich List.

That foray into defence, along with its dominant market share in the industrial explosives market, has meant that the company’s market capitalisation has grown by some 1,700 percent in a decade—from ₹1,765 crore in 2012 to over ₹35,000 crore as of November 2022. In the process, Nuwal, whose family holds a 73 percent stake in the company, has seen his wealth swell to $3 billion, making him India’s 72nd richest person on the 2022 Forbes India Rich List.“I can only say it’s Almighty’s grace,” Nuwal says about featuring on the list. “We have seen so many companies and so many people who have gone to the top level, and sometimes after five or 10 years, they come down. Then you don’t remember if they were there or not. It all depends on the Almighty and hard work.”That ability to remain nonchalant, and perhaps cauti

ous, comes from having begun with nothing after he was forced to leave his hometown in search of a better future for his family.

Also read: The rupee may be weaker, but the rich are richer

Finding his Opportunity

The rise to the top wasn’t easy for Nuwal, who has lately begun sporting a well-trimmed beard and a Nehru jacket. It’s the quintessential rags-to-riches story—he has slept at railway stations because he couldn’t afford to pay for a stay and dabbled in multiple businesses before finding a firm footing in a line of business that hasn’t produced many billionaires in the country.“I belong to a very small town,” says Nuwal, who grew up in Bhilwara, Rajasthan, where his father worked for the government as a patwari (village accountant). After class 10, Nuwal spent a year with his gurudev in Mathura, while also trying his hand at small businesses. “More than education, I was interested in doing business,” he concedes.

After returning to Bhilwara following his stint in Mathura, over the next seven years Nuwal dabbled in numerous businesses, including manufacturing ink for fountain pens, a leasing business and a transport company. “At 18, I started a small business for chemicals and trading, but somehow I could not become successful,” he says. By 19, Nuwal got married. “Up to 1976-1977, I struggled in business, and finally I went to Chandrapur in Maharashtra in 1977,” he continues. Nuwal had moved there since a relative had worked at Western Coal Fields Limited.

In Chandrapur, Nuwal would often sleep at railway stations since he couldn’t afford to pay for accommodation. “I did not lose my confidence,” he says. “I wasn’t disappointed… I was very confident.” There, Nuwal met Abdul Sattar Allah Bhai, who owned an explosives licence and a magazine, but wasn’t actively pursuing the business. Back in the 1970s, India was still in a Licence Raj regime which meant that magazine licences were tough to come by. “Explosives were in shortage then and I came to know that although he had a licence, he wasn’t doing the business,” recalls Nuwal, who agreed to pay him ₹1,000 to rent the magazine. Magazines are places where ammunition and other explosives are stored. “He agreed to rent on a consideration of ₹1,000 per month, but I did not even have that,” says Nuwal. “I went back after a day and requested him. He told me, ‘Don’t worry beta, you can pay me quarterly’.”

In Chandrapur, Nuwal would often sleep at railway stations since he couldn’t afford to pay for accommodation. “I did not lose my confidence,” he says. “I wasn’t disappointed… I was very confident.” There, Nuwal met Abdul Sattar Allah Bhai, who owned an explosives licence and a magazine, but wasn’t actively pursuing the business. Back in the 1970s, India was still in a Licence Raj regime which meant that magazine licences were tough to come by. “Explosives were in shortage then and I came to know that although he had a licence, he wasn’t doing the business,” recalls Nuwal, who agreed to pay him ₹1,000 to rent the magazine. Magazines are places where ammunition and other explosives are stored. “He agreed to rent on a consideration of ₹1,000 per month, but I did not even have that,” says Nuwal. “I went back after a day and requested him. He told me, ‘Don’t worry beta, you can pay me quarterly’.” Over time, as people became aware that Nuwal’s magazine was available to rent, deposits began swelling, as clients were looking for ammunition storage, particularly for use in coal mines. Manufacturing of ammunition back then was largely done by ICI, and by 1984, Nuwal expanded his business to become a consignment agent, becoming one of the largest dealers in the explosives business in India by the 1990s.

“We were growing our business, but in the 1990s, the government gave manufacturing licences to smaller companies due to a shortage of business,” Nuwal says. “After 1992, small companies set up their units and competition began to grow.” The billionaire, who then traded mostly with ICI, and large firms like IBD, and Ideal Chemicals (now known as Gulf Oil), realised that their monopolistic mindset could backfire in the long run, leaving him stranded.

“Big companies were in other businesses,” says Nuwal. “I thought if we needed to grow, it was not worth it to carry out the trading business. We set up our small-scale manufacturing unit in Nagpur in 1996.” That meant that Nuwal had to give up his rights as a consignee for ICI. “I knew it was very risky for me,” he says.

Also read: Romesh Wadhwani: Building up, and giving away

Solar Industries’ defence plant in Nagpur. In July this year, the company became the first indigenous supplier of boosters for the Brahmos missiles

Solar Industries’ defence plant in Nagpur. In July this year, the company became the first indigenous supplier of boosters for the Brahmos missilesStepping up to Glory

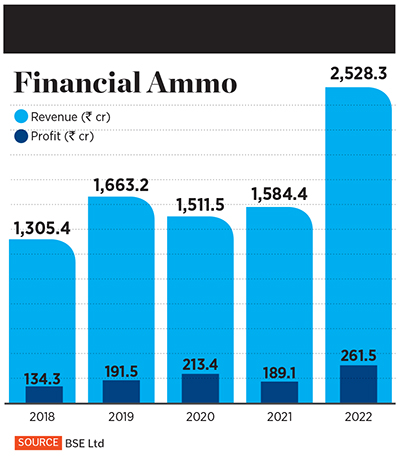

Nuwal raised ₹60 lakh through loans and other savings, and set out to manufacture slurry explosives. Soon, the company also forayed into manufacturing detonators and bulk explosives. Among his single biggest client over the years has been India’s state-controlled Coal India, which uses Solar Industries’ explosives for its mines. “Within 10 years, we became the largest manufacturer of explosives in the country,” claims Nuwal. About 70 percent of the bulk explosives are used in coal and other metal mines in the country, in addition to exports.By 2006, the company decided to go public when its turnover was ₹78 crore with a net profit of around ₹11 crore. The money was largely used to set up 13 manufacturing plants and expand the business. Since then, Solar Industries has expanded its manufacturing facilities to 29 cities across nine states, in addition to six overseas units in Zambia, Ghana, Nigeria, Turkey, Tanzania and South Africa. The company is currently setting up manufacturing bases in Australia, Thailand and Indonesia.

By 2010, Solar Industries was the first private company to get a licence from the government to make explosives for warheads for India’s defence forces. “Our country was heavily dependent on imports,” says Nuwal. “Since we had experience in explosives, we could go into ammunition later.”

By 2010, Solar Industries was the first private company to get a licence from the government to make explosives for warheads for India’s defence forces. “Our country was heavily dependent on imports,” says Nuwal. “Since we had experience in explosives, we could go into ammunition later.” Around the same time, Nuwal, the wily entrepreneur, also realised that sooner or later ammunition will have to be manufactured in the country. He set about building capacity to expand into ammunition, including grenades and medium and large caliber ammunition, in addition to high energy explosive (HMX) and HMX compounded products, propellants and warheads.

“So, it was very risky… there was no plan by the government to give complete ammunition to the private sector due to security factors,” explains Nuwal. “But somehow I decided that if we can manufacture a good product, at a globally competitive price, the government has to change its thinking.” The move was rather bold, especially since India was heavily reliant on imports, and manufacturing of defence equipment was largely carried out at nine state-owned companies and 40 ordnance factories under the ministry of defence.

“The Ordnance Factory was a monopoly, and we had two big players in BDL and BEL,” says Nuwal. “There was no chance for anybody to come up in the private sector. But I decided we should. We got our first industrial licence in 2015 for ammunition,” says Nuwal. Since then, for the first time in India’s defence history, Solar Industries became the first private company to win an ammunition order for the supply of multi-mode hand grenades (MMHG) worth some ₹450 crore, to be delivered over two years.

The company also has orders for making propellants for the Akash missile, a medium-range surface-to-air missile, and the Pinaka, a multiple rocket launcher, used by the country’s defence forces, as well as for pyrotechnics, which helps initiate the explosion, and igniters, which provide the spark for the ammunition. In July, Solar Industries became the first indigenous supplier of boosters for the Brahmos missiles, a medium-range missile that can be fired from submarines, ships, aircraft or land.

Solar Industries has a current order book of nearly ₹4,000 crore and in the last fiscal turned revenues of ₹3,948 crore. Around 40 percent of its revenue comes from exports with the defence sector expected to contribute some 18 percent in the coming months.

India accounts for 3.7 percent of the global military spending, making it the world’s third-largest military spender. By 2025, the government wants to reduce its dependence on imports significantly and plans to build a sector with a turnover of $25 billion. So far, 351 companies have received 568 defence industrial licenses from the government as part of that initiative; of these, 113 have announced commencement of production.

Also read: Dasari Uday Kumar Reddy—the billionaire founder who swears by his 4 am regime

Strong, Stronger, Strongest

In August, India’s defence acquisition committee (DAC) cleared Solar Industries to compete in bids to manufacture two versions of the Pinaka rockets. The company was the first private sector company to qualify for manufacturing the rockets. “In the ammunition business, you need a lot of patience,” says Nuwal. “Whatever technologies you have, it takes time with trials and approvals.” Already, Armenia has signed a deal to import rockets and missiles from Solar Industries.The company has also submitted proposals to manufacture two High Mobility Long Range Precision Rocket Systems, Maheshwarastra 1 and Maheshwarastra 2, under the Make II category of the Make in India initiative. Under the Make II initiative, companies build prototypes of equipment and systems without funding support from the government. Maheshwarastra 1 will be a Multi Barrel Guided Rocket Launch System with a range of 150 km while Maheshwarastra 2 will have a range of 250 km.

“The Brahmos missile costs around ₹40 crore, but our missile price is only ₹8 crore,” claims Nuwal. “Where the Brahmos warhead is 250 kilos, ours is 375 kilos. The only difference is that Brahmos has a seeker. We can also deploy the seeker which costs ₹3 crore.” Nuwal is also building two weapons, which he claims are first-of-their-kind, that detect mines and destroy them.

Check out the complete lndia's 100 Richest 2022 list

Then, there is a counter-drone system, named Bhargavastra, which can destroy up to 16 drones in seven seconds, and deploy 64 missiles through its system. The company has already tested the mechanism. “If we should go fast, we need to invest from our end,” says Nuwal. “Within two years, we will complete making counter-drones.”

Nuwal is gearing up to invest some ₹600 crore towards developing the three programmes. Avinash Chandra, former chief of DRDO, and Manjit Singh, a former director of Terminal Ballistic Research Laboratory, among others, have joined the group to assist him in his mission. The company is currently the only one to cross annualised production of 300,000 MT of explosives.

That rapid pace of growth has also meant that Nuwal is now looking to potential startups, especially in the unmanned aerial vehicle segment and defence segment, to expand growth. In 2019, the company made an angel investment in Skyroot Aerospace, which became the first Indian private company to demonstrate the capability to build a homegrown rocket engine and successfully test-fired an upper-stage rocket engine.

In April, the company also acquired a 45 percent stake in ZMotion Autonomous Systems Private Limited, which manufactures the weaponised unmanned aerial vehicle. “The company has taken a strategic decision to make an investment in North India-based explosive manufacturing company (RECL) after making recent investments in Skyroot and Zmotion to increase the product portfolio for various high-end applications and enhance geographical footprints,” brokerage firm ICICI Direct wrote in a recent report. “Going forward, the management projects an inflationary environment and consequential policy rate tightening measures to impact the global demand,” the report adds.

“However, the government’s thrust on housing and infra, rising coal demand, and Atmanirbhar Bharat promoting towards indigenisation of defence products will enable the company to achieve the expected annual growth guidance. Defence continues to be a catalyst to the company’s top-line growth, and to escalate the progress, the company has taken the initiative to penetrate the field of drones, embracing both offensive and defensive roles of these equipment.”

All that means is that Nuwal is keeping himself busy at work. While his son Manish, CEO and managing director of Solar Industries, executes his father’s vision, and looks after day-to-day operations, Nuwal’s schedule often sees him travelling to Delhi for seeking permissions and developing the business. He also makes it a point to travel back to Bhilwara—from where it all began—thrice a year.

“My 96-year-old mother is still there,” Nuwal says. “And she is certainly proud of what we have done so far.”

At 70, Nuwal has only tapped the tip of the iceberg when it comes to defence manufacturing. There are tremendous avenues in the sector, especially considering India’s geopolitical situation, and he is only getting started.

(This story appears in the 15 December, 2022 issue of Forbes India. To visit our Archives, click here.)

Post Your Comment