Mad Over Donuts: Lord of the glazed rings

A decade of frenzied euphoria, an intense scramble for a bigger bite, and recoiling of a flurry of doughnut brands have paved the way for an unlikely winner. Interestingly, the maddest about doughnuts has managed to survive, flourish, and make money

Tarak Bhattacharya, Executive Director & CEO at Mad Over Donuts.

Image: Mexy Xavier

Tarak Bhattacharya, Executive Director & CEO at Mad Over Donuts.

Image: Mexy Xavier

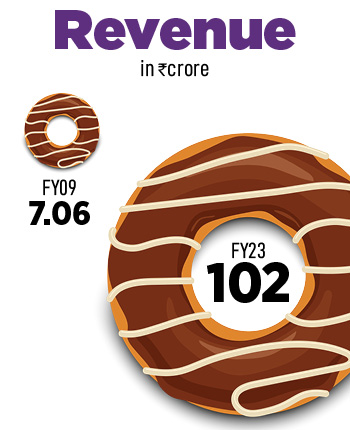

Mumbai, August 2013. Tarak Bhattacharya was a bit edgy. It had been a little over five years since the doughnut brand from Singapore—Mad Over Donuts (MOD)—opened its account in India. The first store came up in March 2008 at Noida, some 25 kilometres from Connaught Place, the heart of Delhi, and by the first half of 2013, the brand had plodded along to two dozen outlets across Delhi-NCR, Mumbai, Pune and Bengaluru. Though sedate, the journey was commendable for a raft of reasons.

Third, doughnut had too many desi competitors in mithai, desserts and yes, chocolates. Given the not-so-sweet market realities, Bhattacharya should have had a glazing look on his face. Back in August 2013, he was looking a bit pale. “I was just anxious,” recounts the chief executive officer who joined MOD in 2011. “I was not scared.”

Well, Bhattacharya had all the reasons to be worried, and scared. The big daddy of doughnuts—Dunkin Donuts—did something unthinkable in India. Over a year into the country, the Indian master franchise of Dunkin Donuts—Jubilant FoodWorks—rolled out burgers: Classic and smoked chicken, potato hash brown burger and spicy veg. A brand globally known for doughnuts was about to sell burgers! What this meant for rivals was one simple thing: More footfalls, more stickiness and more business for Dunkin, which bared its aggressive intent by racing to 14 outlets in Delhi-NCR and Chandigarh in just a little over 12 months.

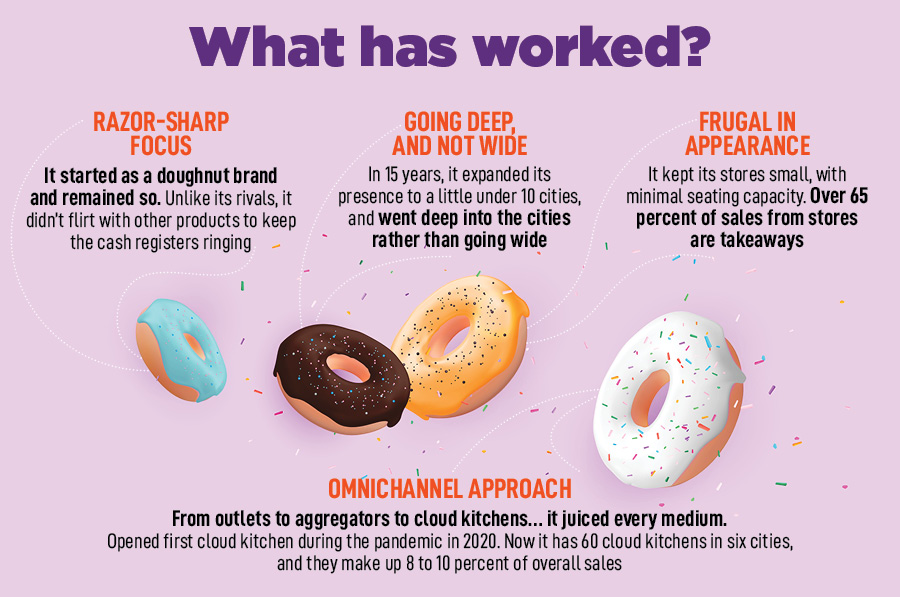

MOD, in contrast, was 24 in 65 months, and Bhattacharya was still committed to the product and Indianisation by rolling out kaju katli, motichoor, and gulab jamun-flavoured doughnuts. “A doughnut brand must persist with doughnuts, right?” he asks. Though the rapid pace of expansion of the rival American giant was alarming, Bhattacharya preferred to look at the topping: The market was expanding, more people were trying doughnuts, and the product had a fighting chance to be more than just niche. There was another reason to be perturbed, though. Another American doughnut goliath—Krispy Kreme—had set foot in the country in January 2013, and planned a brisk ramp-up: 80 outlets in five years. Then there was a clutch of other doughnut brands—The Donut Baker, which had opened stores in Bengaluru; Donut Empire and Donut Factory—which wanted a bigger bite of the market. MOD, it seemed, was getting ringed on all sides.

Also read: Can Papa Johns take on big daddy Domino's?

Three years later, MOD was dunked on by the much bigger American rival. During the last quarter of 2016, Dunkin Donuts was reportedly at 77 stores in 23 cities. MOD, on the other hand, was 48, and confined to Delhi-NCR, Mumbai, Pune and Bengaluru, and was no longer the biggest brand. “For seven years, 2013 till 2020, we didn’t expand horizontally,” says Bhattacharya, who was still a purist in terms of offering, and had internalised the reality that doughnuts were at best a snack item, and one could try multiple ways to increase the occasion for snacks, but couldn’t compete with burger, pizza or biryani in terms of ticket size or frequency of orders.

Meanwhile, the CEO stayed relentless in extensive sampling of doughnuts: From traffic signals, schools, colleges, malls and markets. “Trials helped a lot in getting stickiness,” he underlines, adding that the brand was also religious in regularly rolling out ‘flavour festivals’ to interact with consumers, which had an unintended benefit: Feedback. MOD rolled out bite-sized doughnuts to satiate the cravings of its users.

Though lavish in trials, MOD remained frugal in its approach. Bhattacharya experimented a lot with the size of the stores to figure out the best cost efficiency and operational structure. From a signature store of 1,000 sq ft in Noida—and he stayed away from the temptation to open a battery of signature and opulent stores—the store sizes kept fluctuating from 800 sq ft, 600 sq ft, 440 sq ft and 145 sq ft. By the end of 2019, the brand had 65 stores, and a dominant share of sales was happening in the form of takeaway from the outlets. Bite-sized product, bite-sized format and bite-sized content… Bhattacharya was gladly dunked in his doughnut world.

And then came Covid in the first quarter of 2020. Stores were shut, discretionary spending came to a screeching halt—doughnuts were an indulgence and not a necessity—and business dipped. Cloud kitchens, interestingly, came as a silver lining. MOD opened the first in 2020, and over the next three years, it spread to six cities—Mumbai, Delhi, Pune, Bengaluru, Chennai, Ahmedabad—with 60 outlets. “They (cloud kitchen outlets) now contribute 8 to 10 percent of the revenues,” he claims. Cloud kitchens, he adds, not only helped the brand survive the crisis—they formed around 50 percent of revenue during the pandemic years—but also helped it expand its footprint without spending expensive dollars in opening stores. By the end of last year, MOD had 140 stores, out of which 60 were cloud kitchens. It became the biggest in size in India, reclaimed the crown, and continued with its crisp growth.

Meanwhile, the doughnut story took a brittle turn for a host of players. Let’s start with Dunkin Donuts, which globally dropped ‘Donuts’ from its branding, and focussed sharply on coffee. The impact was seen in India, where Dunkin progressively tumbled in count, reach and diverse and unrelated product offerings. From 77 outlets and 23 cities in the first quarter of 2017, Dunkin shrunk to 21 outlets and 11 cities by the end of the second quarter of FY24. In fact, 11 of the 21 stores now reflect the brand's coffee-first identity. Krispy Kreme too tempered down its ambitions and settled for a small presence in Bengaluru. A bunch of other upstarts either shuttered or became inconsequential in presence. Doughnuts became a difficult nut to crack for all.

The performance of MOD, reckon branding and marketing experts, has to be evaluated against the context of how it stayed away from the mad scramble to open outposts across scores of cities in a short span of time. “Doughnut is not dosa or idli or samosa,” says Ashita Aggarwal, professor of marketing at SP Jain Institute of Management and Research. It will always have its consumers, but the frequency would be restricted. Anybody opening a doughnut shop in India and thinking that it can make quick and big money is unrealistic. “You can’t just sell burgers or fries or pizzas under the doughnut brand to make money,” she says, adding that the business of doughnuts is only meant for those who have loads of patience and stay true to the product. “The fact that MOD realised the folly of matching the firepower of its rivals shows the maturity of the brand in accepting its limitations,” she says. “It played to its strength.”

The performance of MOD, reckon branding and marketing experts, has to be evaluated against the context of how it stayed away from the mad scramble to open outposts across scores of cities in a short span of time. “Doughnut is not dosa or idli or samosa,” says Ashita Aggarwal, professor of marketing at SP Jain Institute of Management and Research. It will always have its consumers, but the frequency would be restricted. Anybody opening a doughnut shop in India and thinking that it can make quick and big money is unrealistic. “You can’t just sell burgers or fries or pizzas under the doughnut brand to make money,” she says, adding that the business of doughnuts is only meant for those who have loads of patience and stay true to the product. “The fact that MOD realised the folly of matching the firepower of its rivals shows the maturity of the brand in accepting its limitations,” she says. “It played to its strength.” The road ahead, though, is challenging. With new-age consumers curbing their instincts for fried, sugar, salt and junk foods, MOD will have to get back to the drawing board to devise a different product and marketing strategy to woo new users. “Anything with too much sugar is a socially ostracised category,” says Harish Bijoor, advertising and marketing guru who runs an eponymous brand consulting firm. “A focussed approach has paid off for MOD, which didn’t flirt with other products.”

Bhattacharya, for his part, reckons that the brand will continue to stick to doughnuts. “Doughnut was always our superhero, and it will remain this way,” he says. Commenting on the state of competition, the CEO underlines that it’s no fun running alone. “The problem is there is no number 2, 3 and 4. That’s the biggest challenge as well,” he confesses. With an established and profitable business model, Bhattacharya underscores that the brand will expand in a calculated manner. “The market has not shrunk. The fact that we grew shows that there is enough headroom for growth,” he says, adding that the brand too had its share of mistakes in terms of opening unviable outlets. “But we were quick to shut them down and course correct,” he says. One can’t be too aggressive in the business of doughnuts. “It has to be sweet, and not too sweet,” he signs off.

Post Your Comment