Welspun's BK Goenka: Spinning solutions

Balkrishan Goenka has been facing challenges since the time he founded Welspun in 1985. The turnaround he has scripted is testament to his indomitable will

Backward integration, a process by which a company produces parts of its supply chain itself, is a strategy that many Indian conglomerates have employed successfully to gain size and scale. But for some business houses like Balkrishan (BK) Goenka’s Welspun Group, it has proved to be a bane rather than a boon.

An adverse order passed by India’s markets regulator Sebi, banning some promoter entities of Welspun from participating in the capital markets due to alleged stock manipulation, added to the company’s problems. (The charges against these entities were vacated by the regulator in March 2012.)

But 50-year-old Goenka, chairman of the Welspun Group, is no stranger to challenges in business. His baptism by fire happened when he chose to move away from the family business of milling food grains to create his own textile manufacturing setup in 1985, when ‘Made in India’ was a concept with little acceptance in the West.

Years later, when he realised the futility of his group’s attempt to move out of its core area of textiles and pipes, Goenka decided to cut losses and correct the conglomerate’s course by selling assets and exiting ventures that were a drag on business. Cut to 2015, and the result of the restructuring that has happened at Welspun over the last four years has resulted in a leaner business with a healthier balance sheet, a better debt profile, encouraging earnings growth at the textiles business and the promise of better times ahead for the steel pipes division.

The momentum at the group, which has businesses like textiles and steel pipes that rank among the top three in the world, has not gone unnoticed and is being rewarded handsomely by investors. For instance, since September 22, 2013, Welspun India Ltd (WIL)—the textiles company that manufactures terry towels and home linen—has seen its share price multiply almost 14-fold from Rs 61.75 (on September 22, 2013) to Rs 832.20 per share (on September 22, 2015). In the same period, Welspun Corp Ltd (WCL), which makes steel pipes, has seen its stock climb 262.2 percent from Rs 31.10 to Rs 112.65 per share.

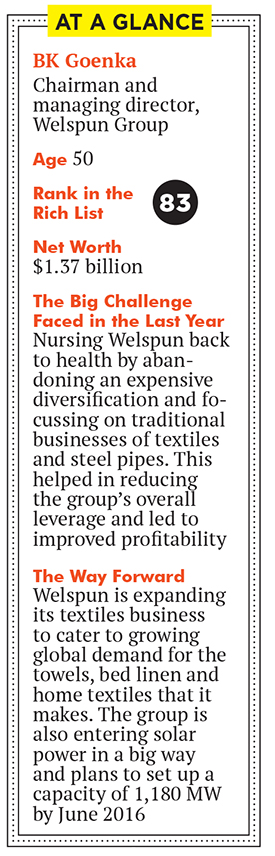

The stupendous growth in the group’s market value implies that Goenka’s personal wealth (including the value of his 73.49 percent stake in WIL and 40.92 percent stake in WCL) has risen as well and gained him a re-entry into the Forbes India Rich List after a gap of four years. Goenka ranks 83 on the 2015 Forbes India Rich List, with his personal wealth estimated at $1.37 billion.

Goenka, who did not pursue any formal education after completing school, belongs to a traditional Marwari joint family of traders that shifted base from Rajasthan to Haryana and then to Delhi. His education involved discussions on business over family dinners and time spent with his grandfather learning how to read and write a balance sheet in the red ledger books of those days.

By the time he was 18, he decided to start his own business. After briefly trying his hand at brass exports in London, he returned to India and set up base in Mumbai. Armed with a seed funding of Rs 20 lakh, given to him by his father Gopiram Goenka, and non-fund-based payment guarantees from Canara Bank worth Rs 80 lakh, Goenka set up a small textile unit in Palghar, Maharashtra. That was the beginning of Welspun India Ltd, which went public in 1991. But the journey was no smooth sailing.

One of the first challenges that Goenka encountered was a lack of faith, among prospective international buyers, in the quality of products made in India. “The first prospective customer to whom we showed a towel manufactured at our plant in India refused to believe that we had made the product,” says Goenka. “Given the good quality of the product, they thought we had sourced it from somewhere abroad and put our own label on it. We had to bring this customer to India and show him our textile unit before he believed us.”

There were other challenges like the high cost of debt and infrastructure bottlenecks. Goenka recalls an instance when an export consignment reached the Mumbai port late due to poor road connectivity and could not be loaded on to a ship. “Though air freight was ten times more expensive, we airlifted the towels. It was like sending the dollars along with the towels,” says Goenka. But it was necessary for WIL to bear the additional expenditure in order to build its reputation as a reliable supplier.

The other hurdle Welspun faced was the many layers of middlemen that came between WIL and its prospective clients in the US. These agents and distributors not only ate into the company’s margins but also prevented it from interacting directly with customers to understand their product requirements. Goenka worked his way around this barrier by assiduously interacting with his clients in the US and consistently delivering on the timelines and quality parameters he had committed himself and his company to. “We were able to convince the buyers that if we were allowed to interact directly with them, it would help us serve them better,” says Goenka.

Over the last 15 years, WIL has painstakingly established a considerable degree of goodwill with its clients that include marquee retail chains like Walmart, JCPenney, Macy’s and Kohl’s. It has managed to weed out the chain of agents and distributors in between. It is the largest exporter of home textiles to the US at present.

Even as large conglomerates like Reliance Industries, which started off as a textile manufacturer, diversified its supply chain to make petrochemicals, refined crude products like petrol and diesel and explore hydrocarbons (textiles is a miniscule part of the Mukesh Ambani-led group at present), WIL continued to grow the textile business successfully. (Reliance Industries owns Network 18, the publishers of Forbes India.)

But an aggressive expansion plan to grow the textile business globally between 2006 and 2008 proved to be a stumbling block for Goenka. Acquisitions of textile making units in the UK, Mexico, Portugal and Argentina did not work out due to high costs of production there. Within four to five years of acquiring them, WIL had to shut down its Mexico and Argentina units, and sold the Portugal business back to the original owners.

In 2006, WIL acquired Christy, a UK-based household linen manufacturer, which, to this day, is the sole supplier of towels used by tennis players at Wimbledon. Subsequently, in 2010, WIL shut down Christy’s manufacturing unit in the UK and moved production to its facilities in India, while continuing to maintain the brand. “We lost around Rs 180 crore over a period of three years on account of these ventures,” Goenka says.

WIL also expanded its retail outlets in India substantially but soon realised that standalone stores were not attracting sufficient footfalls. So next to go were around 200 retail stores that the company had in India, in favour of large format retail chains like Shopper’s Stop and ecommerce stores. The revised strategy has had a positive impact on WIL’s financials. The company reported a consolidated net turnover of Rs 5,202.50 crore in FY15, more than double of what it did in FY11. Its net profit in the same period grew 38-fold to Rs 539.79 crore.

Even as Goenka was building the fortunes of WIL, he was also spearheading Welspun’s growth in the steel pipe manufacturing business in 1997. But the resistance WCL faced was akin to his experience in selling towels to global buyers. The first order that it won was to supply steel pipes for Enron’s gas-based power plant in Dabhol, Maharashtra. When the energy company’s senior management based in the US expressed their reservation in awarding the contract to a new entrant like Welspun, they were flown to Vapi, Gujarat, to see the group’s thriving textile business in operation. According to Goenka, they even spoke to WIL’s customers in the US before being convinced of the Indian business group’s ability to deliver on its promises.

The strategy worked and WCL got the order. But an accounting fraud at Enron that led to its bankruptcy in 2001 meant that its stalled project in India no longer needed Welspun’s pipes. But in many ways, the energy project was responsible for facilitating WCL’s entry into the export market: Several technical experts who quit Enron to join other international firms recommended WCL as a trustworthy vendor to their new bosses.

Welspun’s steel pipes business took off, and today, the company counts leading global energy companies including ExxonMobil, Shell and BP, and Indian players like state-run Oil and Natural Gas Corporation Ltd (ONGC)and GAIL (India) Ltd as its customers.

Then in 2009, WCL decided to acquire Vikram Ispat, the sponge iron business of the Aditya Birla Group’s Grasim Industries located in Maharashtra, for Rs 1,030 crore. To do so, it had tied up with around 20 banks and raised about Rs 700 crore. The acquisition was to help Welspun integrate backwards as an iron ore-to-steel pipes producer. But trouble arose when Goenka wanted to put up a new steel slab-manufacturing unit as part of the same project. WCL failed to secure environmental clearances for the proposed expansion and had to ultimately sell the project to Sajjan Jindal-led JSW Steel in 2014 for Rs 1,000 crore.

Before selling the plant to JSW Steel, Welspun had already sunk in around Rs 300 crore into the project on account of pre-operative expenses. But the sale—aided by the fact that JSW found the asset attractive as it had synergies with its steel mill—helped WCL repay the debt it took, to acquire Vikram Ispat and expand the project, from banks. “After losing money for almost two-and-a-half years, we were fortunate to find a buyer in JSW Steel for the plant. It was a win-win situation for both companies,” says Goenka. “There are around 1,000 acres of land at the project site and finding that kind of land in Maharashtra isn’t easy anymore.”

SP Tulsian, a Mumbai-based stock market analyst who has been closely following Goenka’s businesses, says the strategy of backward integration did not work for Welspun because it was attempting to execute it in a capital-intensive sector like steel, where each step of reverse integration is ten times more expensive. Also, the steel industry hasn’t exactly been the best-performing sector in the country with prices under pressure due to slack in infrastructure creation and pressure from cheap Chinese imports.

WCL has since returned to its core business of making steel pipes and reported a turnover of Rs 8,450 crore in FY15, up 10 percent from the year ago. Its net profit in the same period fell 6 percent year-on-year to Rs 690 crore. The decline in profitability and subdued growth in topline compared to the textiles business is due to the weakness in global demand for steel pipes. Many of Welspun’s customers in the oil and gas segments have put off their exploration plans due to weak crude oil prices. But WCL’s business picked up during the last quarter of fiscal 2015 and Goenka expects the trend to continue as operators across the world look to reduce operating costs by transporting crude through pipelines instead of the more expensive seaborne tankers.

Goenka, however, has not entirely abandoned his ambition to diversify. He is bullish about renewable energy, especially solar power, though this is not his first foray into energy.

Before the financial crisis of 2008, the Indian economy was expected to do well, and most business houses wanted to get into the infrastructure and power generation segments. Welspun, too, joined the bandwagon. But due to the economic slowdown over the last five years and local challenges in securing linkage to fuels such as coal, it had to abandon its plans to set up thermal power plants and execute infrastructure projects. But this wasn’t before the group invested around Rs 1,000 crore to create the necessary capacity to execute such projects through acquisitions and procurement of land for the power projects. Welspun has since sold the infrastructure companies it had acquired, as well as the land parcels earmarked for the power projects.

At its peak, the Welspun Group had a net debt of around Rs 9,000 crore (in FY13). Goenka reduced this to Rs 5,000 crore, but has since borrowed additional funds to finance its expansion into solar power, a new avenue of growth identified by the group. Consequently, as of March 31, 2015, the group’s debt stands at Rs 8,000 crore.

Welspun wants to build a solar power generation capacity of 1,180 MW by June 2016, out of which around 500 MW is already operational. Tulsian points out that the new debt that Welspun has taken on to finance its fledgling solar power business is unlikely to be a burden on the group as the market for solar power in the country is promising with the government offering impetus to the sector. The Indian government aims to develop 100 GW (1 GW is 1,000 MW) of solar power in the country by 2020.

“The renewable power that Welspun will produce is covered under power purchase agreements and cash flows from sales can be used to service this debt,” says Tulsian.

The group plans to invest around Rs 15,000 crore to develop renewable energy and upgrade its textile plants. Out of this, Rs 7,000 crore has already been spent. Welspun needs to spend this money if it is to realise Goenka’s new vision: He would like Welspun to achieve a turnover of $5 billion by 2020.

It is an ambitious milestone, but then, Goenka isn’t averse to challenges. Investors, too, believe that he will achieve this goal. He has always had a “fighting spirit”, says Tulsian recalling the time when certain competitors had tried to edge him out of the steel pipes sector when Welspun was a new entrant. It is this indomitable will that will see Goenka through the challenges ahead. Not one to throw in the towel, he points out that his group has faced a new challenge roughly after every seven years—in 1992, 1999, 2007 and in 2014—but has been successful in overcoming them since giving up “is not in his DNA”.

Given the turnaround he has scripted, the Welspun Group may have a different and encouraging story to tell in 2021.

(This story appears in the 29 October, 2015 issue of Forbes India. To visit our Archives, click here.)