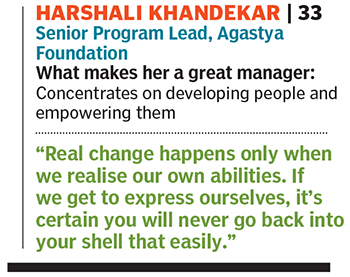

Harshali Khandekar: Open to dialogue

At Agastya Foundation, Harshali Khandekar tries to empower both students and her team

Harshali Khandekar

Harshali KhandekarImage: Mexy Xavier

“In design thinking, you try and use whatever you know and apply that knowledge in bettering the situation around you. In this particular project, we had a set of tools, cutting and drilling tools, and digital tools like 3D printers and computers,” says Khandekar, who along with a colleague, first worked on developing the curriculum for the project for a month-and-a-half before they took it to schools. The idea, she adds, was to encourage children to start finding things that bother them about their surroundings, and come up with and build solutions from whatever material was at hand. Among other things, children transformed abandoned classrooms into lunch/garden/reading areas and built cycle stands, continuing to think about solutions long after the project had left the school.

Khandekar, who did her Masters in biotechnology , followed by a PhD at the Institute of Chemical Technology in Mumbai, joined Agastya Foundation three years ago since a corporate job didn’t appeal to her. “I wanted to work in education, especially with children in their foundation years, making science interesting for them,” she says. Agastya Foundation, which works on helping spark curiosity and nurture creativity through hands-on science education for poor rural children and teachers, fit the bill.

The approach ensured it was not just the children who were empowered, but also the instructors. “We were never scared to speak up about the problems that arose,” says Jyoti Salunkhe, one of the instructors, “and solutions also came up easily.”

(This story appears in the 09 October, 2020 issue of Forbes India. To visit our Archives, click here.)

Post Your Comment