How Ravi Modi built the Manyavar empire

Ravi Modi has spun a small loan from his mother into a wedding wear empire, making the low-key entrepreneur one of India's newest billionaires

Ravi Modi, chairman and managing director, Vedant Fashions

Image: Courtesy Vedant Fashions

Ravi Modi, chairman and managing director, Vedant Fashions

Image: Courtesy Vedant Fashions

While the shop sold jeans, T-shirts, trousers and shorts for men, it didn’t offer any traditional Indian wear. “There was demand but no supply,” says Modi. He tried convincing his father to sell men’s kurtas and pajamas but that didn’t work. So when his father was away on an annual pilgrimage in 1996, the then-19-year-old Modi sourced 100 men’s kurta-pajamas sets, selling 80 by the end of the week.

“When my father came back, he was very angry,” recalls Modi, “but when he saw that I’d sold 80 pieces he was happy.”

Thus began a foray into men’s ethnic Indian wear that has made Modi’s franchise-based apparel company, Vedant Fashions, a leading player in the wedding- and celebration-wear market for men, women and children, selling 4 million pieces a year.

In February, Modi listed 15 percent of the company on the Indian stock exchanges—the basis of his $3.75 billion fortune that adds him to the ranks of India’s richest.

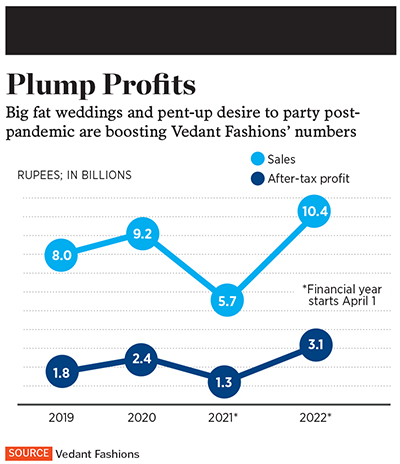

Vedant Fashions’ numbers should give Modi cause for celebration. Its revenue rose 84 percent to ₹10.4 billion ($138 million) in the year ended March 31, while after-tax profit more than doubled to ₹3.1 billion. The strong results reflect a low base in 2021, hurt by Covid-19-related restrictions that put a lid on partying.

Nevertheless, the latest revenue was 30 percent higher than in fiscal 2019, prior to the pandemic, while profit was up 79 percent. Mumbai investment firm Axis Capital predicts revenue and profit will rise at compound annual growth rates of roughly 30 percent over the next two fiscal years. Modi plans to nearly double total retail space in the next few years to 2.4 million sq ft.

Vedant Fashions’ robust earnings and bright future are due to the growing trend of so-called ‘big fat Indian weddings’, which can take place over many days and include not just the wedding ceremony and reception, but also welcome parties, religious rituals and other celebrations.

Vedant Fashions’ robust earnings and bright future are due to the growing trend of so-called ‘big fat Indian weddings’, which can take place over many days and include not just the wedding ceremony and reception, but also welcome parties, religious rituals and other celebrations. According to Mumbai analytics company Crisil, weddings are getting bigger, grander and longer, fueled by higher disposable incomes and a surge in discretionary spending. It expects the ethnic-apparel market to grow between 15 and 17 percent to nearly ₹1.38 trillion by 2025, supported by a growing desire among Indians to wear traditional rather than Western wear for big celebrations.

Vedant Fashions, which Modi started with the Manyavar brand in 1999, caters to men, women and children, selling heritage garments such as pajamas and saris, as well as sherwanis, kurtas, lehengas, and salwar sets. It designs the garments, but outsources most of the manufacturing to third parties, and has 590 stores in 228 Indian cities and 13 stores across North America and the UAE. Its flagship line, Manyavar, provides men’s celebration wear while its Mohey brand, started in 2015, serves women. Both are in the mid-premium, or aspirational-yet-affordable, segment.

Modi, 45, also has premium and mass-market lines for men called Tvamev and Manthan, respectively. In 2017 he acquired rival Mebaz for an undisclosed sum to provide mid-premium and premium outfits in the South India market. The different brands are sold through a combination of exclusive and multibrand outlets, as well as large retailers and online shopping platforms, including its own app.

Ravi Modi (centre) with wife, Shilpi Modi, who sits on Vedant Fashions’ board, and son, Vedant, the company’s chief marketing officer

Ravi Modi (centre) with wife, Shilpi Modi, who sits on Vedant Fashions’ board, and son, Vedant, the company’s chief marketing officerWith a third of the country’s population within marriageable age, from 20 to 39 years, Crisil estimates there are about 10 million weddings a year in India, with daily budgets ranging from ₹1 million to ₹2 million. Vedant Fashions has also identified some 30 festivals and national days for which it promotes its celebration wear, from Eid to Diwali.

Modi, who is chairman and managing director of Vedant Fashions (his son and only child, Vedant, after whom Modi named the company, is chief marketing officer), is gearing up for a robust October-to-December quarter, which will mark the first big wedding season since Covid-19, traditionally falling during the months from November to January.

Also read: Anand Mahindra: Rebel, leader, and master of change

“We are very optimistic about the season,” says Modi, a time that typically generates about a third of annual revenue. “We want to be a dominant player in Indian wear, across genre, across price and across gender,” he says. “The next three or four decades are Indian and anything Indian will sell.”

Modi’s success has come from parlaying an early play in men’s ready-to-wear into a whole new category of branded wedding wear. His mission is to provide a one-stop shopping experience for the whole family, and he is careful to cater not just to different income brackets, but also to regional preferences, by, for example, stocking traditional South Indian dhotis and angavastram, in stores in South India, in addition to the usual sherwanis and kurtas. “The idea was that you could walk into a Manyavar store and come out ready for your wedding,” he says.

Modi’s success has come from parlaying an early play in men’s ready-to-wear into a whole new category of branded wedding wear. His mission is to provide a one-stop shopping experience for the whole family, and he is careful to cater not just to different income brackets, but also to regional preferences, by, for example, stocking traditional South Indian dhotis and angavastram, in stores in South India, in addition to the usual sherwanis and kurtas. “The idea was that you could walk into a Manyavar store and come out ready for your wedding,” he says.Modi benefits from being a first mover in the market, according to Arvind Singhal, chairman and managing director of Gurgaon-based retail consultancy Technopak. “In the 1980s and 1990s, the men’s market was mainly Western-style suits,” he says, “but by the 2000s it had shifted to ethnic wear, driven by a rise in Indian designers and the portrayal of weddings in Bollywood films. Modi saw the opportunity and built a solid business.”

Modi started with company-owned and -operated stores, but moved to a franchise model in 2016. Today, all but four of the stores are franchises, an approach that has allowed Modi to expand without amassing debt, while keeping control over inventory and marketing. He maintains regular communication with franchise owners and there are frequent customer-service training sessions. “The inventory is very well-managed and there is transparent communication,” says Vineet Jain, who operates eight franchise stores in Chennai. “He is very process-driven and systematic. He has data at his fingertips.”

Modi grew up in Kolkata, the third child alongside three sisters. His father was a first-generation entrepreneur who started a clothing store in 1975 under the name of one of Modi’s sisters, Vandana. It was in Kolkata’s popular AC Market, one of the city’s earliest air-conditioned markets, characterised by small apparel, jewellery and electronics stores. Modi took a keen interest in the business from the age of 13.

Also read: Satyanarayan Nuwal: From sleeping on railway platforms to building the Rs 35,800 crore Solar Industries

Within a year or two, he was practically running the 140-sq-ft store, managing the accounts, inventory and sales. The media-shy entrepreneur, who didn’t even attend his own company’s listing ceremony, found his calling in selling, taking on challenging customers and encouraging them to buy more. “If a customer came to buy one garment and you sold one garment, you are doing the job of a postman,” says Modi. “My first kick was in selling to customers who wouldn’t buy.”

In 1999, Modi branched out on his own, launching the brand Manyavar, which means “respectability” in Hindi, with the tagline, “earn your respect”. He started with one employee and ₹10,000 borrowed from his mother, selling ready-to-wear kurta-pajama sets for ₹200 apiece to mom-and-pop stores across eastern, northern and central India. “For three years my father was curious, suspicious and not very optimistic,” he says.

But in 2002, the father visited the business, and, “After that he was the proudest father one could have,” says Modi. In a reversal of roles, the elder Modi started overseeing accounts at the company, and continued to do so until his death in 2006. In 2008, Modi opened his first Manyavar store, in Bhubaneswar. Today the brand is the leader in the $400-million branded men’s Indian wedding- and celebration-wear market, according to Axis Capital, contributing the bulk of Vedant Fashions’ revenue.

But in 2002, the father visited the business, and, “After that he was the proudest father one could have,” says Modi. In a reversal of roles, the elder Modi started overseeing accounts at the company, and continued to do so until his death in 2006. In 2008, Modi opened his first Manyavar store, in Bhubaneswar. Today the brand is the leader in the $400-million branded men’s Indian wedding- and celebration-wear market, according to Axis Capital, contributing the bulk of Vedant Fashions’ revenue.Modi emphasises customer engagement. “When a customer walks in, we treat him as a guest,” says Modi. “When he comes for the most important occasion of his life, he should feel… an emotional connection.”

He has a novel approach to customer service, drawn from what he calls his MBA in retailing, earned during his years at his father’s store. “You have to treat angry customers a little better than how you treat the customer who comes to buy,” says Modi. “When customers come for a return or an exchange, they know that they will be treated badly. But if you treat such a customer well, that will create… a bond for life.”

Analysts say that Manyavar’s reasonable prices are also a big draw. Men’s kurtas sell for ₹2,000-5,000 and sherwanis from ₹15,000-30,000. “We’ve democratised aristocracy in India,” declares Modi. Prior to Manyavar, he says, such traditional outfits were only for “important people,” not for the masses. “We don’t charge more and yet we make a good profit,” he adds.

And that, analysts say, is because of savvy inventory management. “Today on a zip code level we can forecast at 93 percent to 94 percent accuracy what will sell and where and when,” says Modi. He also limits dead stock, or stock that hasn’t sold and isn’t likely to, to between 2.5 percent and 3 percent of total inventory.

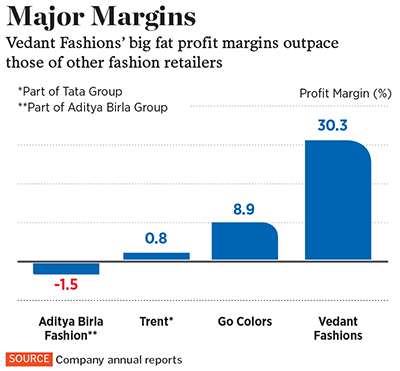

“They have the highest profit margins in the apparel space,” says Gaurav Jogani, consumer analyst at Axis Capital, the investment banking side of which handled Vedant Fashions’ IPO. “That’s because of their asset-light model. They don’t do the manufacturing and they don’t own the stores. So operating expenses are low. They are debt-free and cash-rich,” he says, adding that the brand has “top-of-mind recall.”

Vedant Fashions’ ad spend, at 7.6 percent of revenue, is the highest among apparel retailers, according to Axis Capital. Splurging on everything from billboards to sports sponsorship and ads at movie theaters has made Manyavar synonymous with wedding wear. The company has also roped in high-profile brand ambassadors such as cricketer Virat Kohli and Bollywood stars Kartik Aryan, Alia Bhatt and Ranveer Singh.

However, the competition is encroaching. Technopak’s Singhal warns: “It’s such an obvious opportunity and they have done very obvious things. This is nothing so unique that others can’t do.”

Check out the complete lndia's 100 Richest 2022 list

And others are doing it, starting with Aditya Birla Fashion & Retail, controlled by fellow billionaire Kumar Birla (No 9 among India’s 100 richest), who launched men’s celebration wear at its Tasva stores in 2021.

Additional contenders include listed TCNS Clothing and private players such as FabIndia, Neeru’s, Nalli and Swayamvar. But Modi, who for the past five years has walked the talk by wearing only kurtas and pajamas, is undeterred. “Every 30 or 40 km we have a different culture or different language in India. I think [Vedant Fashions] can provide the common thread to unite this diversified country,” he says.

Modi leads a low-key life in a large bungalow surrounded by a lush green lawn on the outskirts of Kolkata where he grows most of his own fruits and vegetables. With more than 30 years of retail experience under his belt, he has developed a refreshing take on his wealth and career.

“Earning wealth without earning time is meaningless,” he says. After the death of his father, Modi saw that the company could operate without his constant presence. So he took a step back and now measures what he calls ROTI, or return on time invested, in addition to the more conventional ROI, return on investment.

He apportions a quarter of his time to work and wealth management, including philanthropy, and the rest is spent on pursuits relating to health, relationships and learning. His daily activities run the gamut from meditation and yoga to the study of the strategies of retailers such as LVMH, Nike and Uniqlo.

He goes into the office only once or twice a week, but reviews every product line, oversees ads and supervises store expansions. “The market is growing faster than what we were anticipating,” says Modi. “We started this journey saying that people should have at least one Indian outfit in every wardrobe. But now we want every wardrobe to have only Indian outfits.”

(This story appears in the 15 December, 2022 issue of Forbes India. To visit our Archives, click here.)

Post Your Comment